Document 13587564

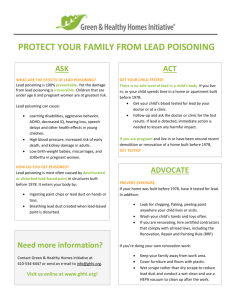

advertisement