Field trip From MIT to MFA

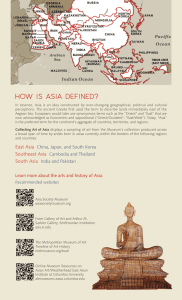

advertisement