When Should Firms Share Credit with Employees? MASSIMO MASSA

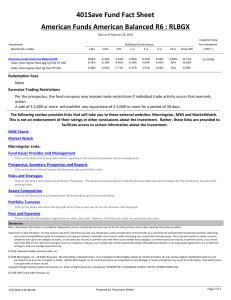

advertisement