Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference

advertisement

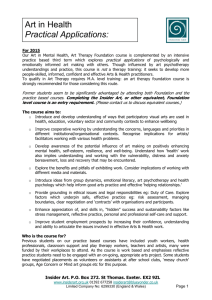

Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 The Performance Effect of Insider Ownership: A Contingent Perspective Te-Kuang Chou This study examined the empirical relationship between insider ownership and firm performance in Taiwan, where the agency problem is typically the one of conflict interests between inside owners (inside directors) and outside shareholders. Based on resource dependency theory, the convergence-of-interests and the entrenchment hypotheses were tested in four industrial settings defined along industry-complexity and firm-scale dimensions via fixed effect panel regression models. The results showed that the convergence-of-interests hypothesis prevailed in the low-industry-complexity and small-firm-scale setting, while the entrenchment hypothesis got support in the high-industry-complexity and large-firm-scale setting. Accordingly, this study inserted a new aspect in the related discussion, arguing that the positive convergence-of-interests effect and the negative entrenchment effect may co-exist in different industrial settings. This argument implies contextual-fitness must be taken into account in searching for effective regulations of corporate governance. Keywords: insider ownership, agency theory, performance, contingent perspective 1. Introduction Since Berle and Means (1932) introduced the concern that the separation of ownership and control could lead to agency problem, the ownership structure of firms has been debated in the management and finance fields for decades. Insider ownership, one of the critical dimensions of ownership structure, is among the focal points of this debate and a suggested way to mitigate agency problem because that a higher insider ownership could help to align managers’ interest with shareholders’ interest (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama, 1980; Jensen and Murphy, 1990; Jensen, 2000). However, the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance was not so clear in empirical studies. There are still competing theories, the convergence-of-interests argument and the entrenchment argument, predicting the performance consequence of insider ownership in opposite directions. More importantly, differences of social-legal context and its profound impacts on ownership structure must be appropriately considered. As some researchers correctly noted, the widely held firms described in Berle and Means’ work does not reflect reality outside the United States and United Kingdom (Faccio and Lang, 2002; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer, 1999). Even the world’s largest listed companies _______________________________________________________________________ Dr. Te-Kuang Chou, Department of Finance, Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Tainan City, Taiwan. 1 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 generally have a concentrated ownership structure (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000; Lins, 2003). In European, Latin American and East Asian countries, founding partners and their families may still in control of a company even after many years after IPO. They and their intimate followers not just run the business as high-rank managers but also sit in the board room as directors (Bozec, Rousseau, and Laurin, 2008; Roosenboom and Schramade, 2006). In this kind of context, the agency problem is subtly changed, from the one of conflict interests between managers and shareholders to the one of conflict interests between inside owners (inside directors) and outside shareholders. This study investigated the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance in Taiwan, where the above-mentioned context is typical. Based on resource dependence theory (RDT) in organizational theory (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Hillman, Withers, and Collins, 2009) and resource-based view (RBV) in strategic management field (Leask and Parnell, 2005; Barney, 2001, 1991; Peteraf, 1993; Wernerfelt, 1984), this study argued that the relationship in concern may varies among different industrial settings. Accordingly, the convergence-of-interests argument and the entrenchment argument were tested in industrial settings defined along industrial complexity and corporate scale dimensions, via fixed effect panel regression models. The results showed that, the convergence-of-interests argument was supported in three of the four industrial settings (low complexity-large scale, low complexity-small scale, and high complexity-small scale), while the entrenchment argument got support in high complexity-large scale setting. Thus, this study inserted a new aspect in the related discussion, arguing that the positive convergence-of-interests effect and the negative entrenchment effect may co-exist in different industrial settings. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature and develops the scope of this study. Section 3 describes the methodology, including data, research variables, and panel regression models. Section 4 presents empirical results and discusses the findings. Section 5 concludes. 2. Literature Review 2.1. Insider ownership and firm performance In their influential 1932 masterpiece, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, Berle and Means first discussed the separation of ownership and control (Berle & Means, 1932). Since that time, numerous theoretical and empirical studies have explored the consequences of ownership structure (e.g. Cullinan et al., 2012; Taboada, 2011; Delios et al., 2008; Patro, 2008; McConnell et al., 2008; O’Regan et al., 2005; Donnelly & Kelly, 2005). As an obvious characteristic of ownership structure, insider ownership has been repeatedly investigated. Nevertheless, no commonly accepted theory regarding the effects of insider ownership has been reached. There are two competing hypotheses in relevant literature regarding the effects of insider ownership on firm performance. The convergence-of-interests hypothesis argues that, an increasing insider ownership aligns manager’s interests with outside shareholder’s, hence results in a positive effect on firm performance. According to Jensen and Meckling (1976), managers are more likely to become self-constrained and avoid consuming perquisites when they hold a higher stake in the firm, because they have to bear the costs of such activities in proportion to their shareholdings. A higher shareholding of insider may resolve the asymmetric information problem related to investment opportunities (DeAngelo and DeAngelo, 1985), reduce agency costs of free cash flow (Jensen, 1986), and mitigate problems of managerial myopia (Palia and Lichtenberg, 1999). Wruck (1988) and Mehran (1995) also provided empirical evidences of positive relationship between 2 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 insider managerial ownership and firm performance. On the contrary, the entrenchment hypothesis suggests a negative effect of insider ownership on firm performance, because higher insider managerial shareholdings will shelter insiders from the influence of market for corporate control (Fama and Jensen, 1983). Insiders tend to secure their positions, build up a business empire for their personal interests, and resist supervision (Jensen and Ruback, 1983). When insiders possess a higher shareholding, which increases their discretion and strengthens their positions, they tend to inflate their own power and damage internal supervisory rules to pursue their own interests (Morck et al., 1988; Gugler et al., 2008). In an attempt to synthesize the two rival arguments, a stream of articles suggested a non-linear relationship between insider shareholding and firm performance. However, the empirical results are even more diversified because of the inherent complexity of non-linear model (Chou, 2013). For example, Morck et al. (1988) presented a N-shaped curve with two turning points to portray the relationship; Hermalin and Weisbach (1991) depicted the relationship as a M-shaped curve with 3 turning points; Cui and Mak (2002) found a W-shaped curve with 3 turning points; Davies et al. (2005) specified a fifth-degree function with two maximum turning points and two minimum turning points; Selarka (2005) found a U-shaped curve with one turning point; Hung and Chen (2009) obtained a V-shaped curve. 2.2. The effect of industrial settings Although agency theory, which both of the above-mentioned competiting hypotheses roots on, is widely used in the research on boards of directors and managers, the studies of resource dependence theory relate external contex to boards of directors provides a promising perspective to synthesize the competing hypotheses. Resource dependence theory characterizes the organization as an open system, dependent on contengencies in its external environment (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Hillman, Withers, and Collins, 2009 for a review). Under the constrain of its resource conditions, organizations attempt to reduce environmental uncertainty by increasing its control over vital resources (Ulrich and Barney, 1984). And bringing in resources is exactly the organizational function served by boards, according to resource dependence theory. “Resource” is a broad term, including all kind of tangible or intangible items useful for firms. However, the resources constitute the competitive advantages of a firm are usually heterogeneous in nature, not perfectly mobile, and not easy to acquire in the market (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993; Crook et al., 2008). Directors of board not only bring in capital (as a block shareholder) but also many intangibles. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) named four types of resource directors could bring in to benefit the firms: (a) information in the form of advice and counsel, (b) access to channels of information between the firm and environmental contigencies, (c) preferential access to resources, and (d) legitimacy. Obviously, all those items are heterogeneous and not available in normal markets. There has been a huge body of literatures on the relationship between board composition and external contex. For example: Mizruchi and Stearns (1988, 1994) provieded empirical supports for the relationship between the firm’s need for financial resources and representation of financial institutions on their boards. Kor and Misangyi (2008) reported a negative relationship between top management’s and the board’s collective levels of industry experience, implying the board supplements top management with critical knowledge and skills. Jones et al (2008) reported that family firms pursuing diversification benefit from specific types of directors over others. All those research articles suggested that directors with specific type of resources help the firms facing their specific environmental contex. 3 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 Some articles within this stream of research are particularly revelant to the current study: Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) found that firms in regulated industries may need more outsiders, particularly those with relevant experience. Provan (1980) found firms invite outside powerful members of the community join their boards are more capable of acquiring critical resources from the environment. Luoma and Goodstein (1999) found that firms in highly regulated industries have a higher proportion of stakeholder directors. Johnson and Greening (1999) found that stakeholder directors are more likely to improve corporate social performance. These researches commonly suggest that in some specific contex, having outsiders or stakeholders join the boards, which implying a lower insider ownership, benefits the firms. Based on these theoretica and empirical researches, this study argues that the convergence-of-interests hypothesis and the entrenchment hypothesis may co-exist in different industrial context. 3. Methodology 3.1 Data and Sample The data used in this study were drawn from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database. Annual data were collected from January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2007 to avoid the effects of legal regulation revision. To ensure completeness of annual data, sample companies were restricted to those listed before January 1, 2004 and continuously listed through December 31, 2007. Sample companies were listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation (TSEC) or were traded through the Over-the-Counter Securities Exchange (OTC). Companies listed on TSEC are typically larger in scale, whereas companies traded through OTC are smaller and typically in their early development stage. The current thresholds of been listed on TSEC are with a contributed capital at least 600 million TWD (about 20 million USD) and has been established and in operation for at least 3 years. To put industrial characteristics in consideration, this study compared technological and traditional industries to detect the effects from industrial complexity. Companies in the electronics and biotech segments were labeled “technological” to reflect its high industrial complexity; meanwhile, companies in the textile, steel, construction, food, chemical, and machinery segments were labeled “traditional” to reflect its low industrial complexity. The number of effective observations totals 1,156. The breakdown of effective observations are 320 in TSEC-technological, 536 in TSEC-traditional, 168 in OTC-technological, and 132 in OTC-traditional. 3.2 Variable Definition and Measurement Insider ownership is the independent variable of this study by nature. We defined insider ownership as the aggregate shareholding of directors and supervisors. This definition is consistent with and comparable to those of existing studies. However, thanks to Taiwan’s minimum shareholding requirement for insiders, this study designed two additional measures to provide a richer observation on insider shareholding. Thus, the three measures of insider ownership used in this study were insider shareholding ratio (ISR), insider shareholding deviation (ISD), and frequency of insufficient shareholding (FIS). ISR is the aggregate shareholding of directors and supervisors over the weighted average outstanding common stock in a given year. This is a fundamental and commonly used measure of insider ownership. ISD refers to the difference between ISR and the legally required minimum shareholding ratio in a given year. ISD is a positive number when the aggregate insider shareholding is higher than the legal requirement. Conversely, a negative ISD shows that the aggregate insider shareholding falls below the legal requirement. FIS is the number of months a firm was filed as insufficient shareholding in a given year. According to Taiwan’s Security Exchange Act, all public companies must file their aggregate insider shareholding every month. Companies are fined if their 4 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 aggregate insider shareholdings are lower than the minimum legal requirements. Thus, the value of this indicator ranges from 0 to 12, which is the number of times in a given year that a company is fined for insufficient aggregate insider shareholding. Earnings per share (EPS) and return on assets (ROA) were adopted as proxies of firm performance respectively, which is the dependent variable of this study. To identify the specific effect of insider ownership, two covariates were used to control statistically for confounding influences on firm performance. Leverage (LEV) denotes the ratio of total debts to total assets, which was included to account for the possibility that creditors are able to lessen managerial agency problems (McConnell & Servaes, 1995; Harvey et al., 2004). Duality (DUA) denotes a situation in which the board chair concurrently holds the position of general manger or CEO. Duality was dummy coded 1 if duality existed in a given year; otherwise, it was coded 0. 3.3 Empirical Models The data used in this study included cross-sectional and time series longitudinal data of the years observed. The fixed effect panel data models adopted to examine the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance was as follows: 𝑬𝑷𝑺𝒊𝒕 = 𝜶𝒊𝒕 + 𝜷𝟏 (𝑰𝑺𝑹𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟐 (𝑰𝑺𝑫𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟑 (𝑭𝑰𝑺𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟒 (𝑫𝑼𝑨𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟓 (𝑳𝑬𝑽𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜺𝒊𝒕 𝑹𝑶𝑨𝒊𝒕 = 𝜶𝒊𝒕 + 𝜷𝟏 (𝑰𝑺𝑹𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟐 (𝑰𝑺𝑫𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟑 (𝑭𝑰𝑺𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟒 (𝑫𝑼𝑨𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟓 (𝑳𝑬𝑽𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜺𝒊𝒕 (1) (2) Here, 𝑬𝑷𝑺𝒊𝒕 and 𝑹𝑶𝑨𝒊𝒕 are the regression dependent variables of company i (i = 1…n) at year t (i = 1…n); 𝜷𝟏 through 𝜷𝟓 are the parameters to be estimated; and 𝜺𝒊𝒕 is the random error. 4. Empirical Results 4.1 Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. It reveals that insider ownership structures are different among industrial settings. Companies in traditional industries tend to have higher ISR, higher ISD, and lower FIS, which implies a high and stable insider shareholding. As presents in the table, the mean of ISR and ISD for TSEC-technological companies is 0.1563 and 0.1361, respectively. Both are lower than the figures for TSEC-traditional companies (0.1922 and 0.1815, respectively). Likewise, the mean of ISR and ISD for OTC-technological companies is 0.2169 and 0.1939, respectively; both are lower than the figures for OTC-traditional companies (0.2479 and 0.1997, respectively). In addition, the technological industry has higher FIS. This echoes that Taiwan’s listed companies in traditional industry typically develop from family-controlled businesses, and insider-owners of such companies tend to have a higher shareholding even after the IPO process. Different insider ownership structures can also be found in TSEC companies and OTC companies. OTC companies have a higher ISR (0.2169 for OTC-technological, 0.1563 for TSEC-technological; 0.2479 for OTC-traditional, 0.1992 for TSEC-traditional) and a higher ISD (0.1939 for OTC-technological, 0.1361 for TSEC-technological; 0.1997 for OTC-traditional, 0.1815 for TSEC-traditional). Meanwhile, OTC companies also have a higher FIS (0.6667 for OTC-technological, 0.2406 for TSEC-technological; 0.3712 for 5 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 OTC-traditional, 0.1063 for TSEC-traditional). The statistics show that insider-owners of OTC companies (typically smaller and/or younger) tend to possess higher shareholding and adjust their shareholding more frequently, which implies a high but unstable insider shareholding. Table 1: Summary of Descriptive Statistics TSEC Companies Mean OTC Companies Standard Deviation Mean Standard Deviation Technological Traditional Technological Traditional Technological Traditional Technological Traditional ISR 0.1563 0.1922 0.0872 0.1485 0.2169 0.2479 0.1430 0.1742 ISD 0.1361 0.1815 0.1426 0.2222 0.1939 0.1997 0.2704 0.2161 FIS 0.2406 0.1063 1.0835 0.7195 0.6667 0.3712 1.6764 0.9839 DUA 0.3719 0.2519 0.4841 0.4345 0.4583 0.2727 0.4998 0.4471 LEV 0.3793 0.4023 0.1484 0.2305 0.4153 0.3963 0.1842 0.2568 EPS 1.4999 0.7371 2.9184 1.8591 -0.3144 0.9189 2.6489 2.4479 ROA 0.0442 0.0205 0.1015 0.0638 -0.0382 0.0224 0.1733 0.0964 This table shows the descriptive statistics. It reveals that insider shareholding structures are different among industrial settings. Companies in traditional AA industries tend to have higher ISR, higher ISD, and lower FIS, which implies a high and stable insider shareholding (comparing with technological industries). OTC companies tend to have higher ISR and ISD, accompanied with higher FIS, which implies a high and unstable insider shareholding (comparing with TSEC companies). AAA A 2: Correlation Matrix Table TSEC Companies ISR ISD ISR 0.9002 FIS *** ISD 0.8763*** FIS -0.1926*** -0.1629*** -0.0501 -0.1177** DUA LEV 0.0779 0.0820 DUA LEV EPS * 0.0557 0.1947 -0.0748* 0.0486 0.0158 -0.0720 0.0141 0.0342 *** ROA *** 0.2141*** 0.0994** 0.1522*** 0.2258*** 0.1349*** -0.0432 -0.0890** -0.0091 -0.0002 0.1140 -0.0574 *** -0.0368 -0.1891 *** EPS 0.0523 0.0149 -0.0899 0.0446 -0.2306 ROA 0.0612 -0.0014 -0.0553 -0.0216 -0.3422*** -0.0490 0.8119*** 0.8800*** OTC Companies ISR ISD 0.8869*** ISR ISD FIS 0.9015 -0.1267 *** FIS DUA LEV EPS -0.0428 0.1584* 0.5825*** 0.1866** -0.0041 * *** 0.1605 * -0.1479 0.0284 6 0.5019 0.1803 ** ROA 0.2404 *** *** -0.3673 0.1128 0.1053 -0.4278*** Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 DUA 0.0105 0.0267 LEV -0.0943 -0.1619** EPS 0.1257 0.1730 ** ROA 0.2097*** 0.2427*** 0.1546* 0.0905 0.0623 -0.0971 0.0010 0.0073 -0.0085 -0.1281 *** -0.0749 -0.0343 -0.2797 -0.1369* -0.0238 -0.1700** 0.8766*** 0.8348*** This table shows the correlation matrixes for TSEC and OTC companies respectively. The lower-left corner indicates technology industries, and the upper-right corner indicates traditional industries. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively. Table 2 presents correlation matrix of independent variables. It can be observed that all the 4 correlation coefficients of ISR and ISD are much higher than others and with statistical significance, which implies a collinearity might exist. After running a variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis, the all-variable-included mode of regression was excluded because of high VIF values (> 10). Instead, the regression models respectively include ISR (Mode A) and ISD (Mode B) were adopted in the following empirical analysis. 4.2 Insider Ownership and Firm Performance The primary results of this study are presented in Table 3. EPS and ROA are the independent variables to perform fixed effect panel data regression in empirical model (1) and (2) respectively. In general, the results of the two empirical models are quite consistent, revealing impacts of industrial settings on the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance. In the results of empirical model (1), ISR and ISD have a positive coefficient with statistical significance in three of the four tested industrial settings (i.e. 5.9776 and 1.2041 for TSEC-traditional, 9.4940 and 6.9018 for OTC-technological, 9.9342 and 1.5757 for OTC-traditional). This implies a higher level of insider ownership induces a better firm performance, concurring in the convergence-of-interest hypothesis. However, the coefficients of ISR and ISD in TSEC-technological setting are negative (-3.4229 and -1.6516) with strong statistical significance (p = 0.0022 and p = 0.0025 respectively), implying a support for the entrenchment hypothesis. Similar results can be found in empirical model (2), which uses ROA as performance proxy. In the results of model (2), the TSEC-technological setting was discriminated from the other three with negative ISR and ISD coefficients (-0.1835 and -0.0920) with strong statistical significance (p = 0.0000 and p = 0.0013 respectively). The industrial setting effect can also be found in the empirical results on FIS, though different from ISR and ISD. As shown in Table 4, the only circumstance that FIS has negative coefficients is OTC-traditional. In empirical model (1), the FIS coefficients are -0.3971 (Mode A) and -0.4286 (Mode B) with strong statistical significance (p = 0.0008 and p = 0.0016 respectively). Same results can be observed in empirical model (2), with statistical significance a bit lower (p = 0.0159 and p = 0.0625 respectively). Recalling FIS is an indirect measurement of insider shareholding, it surely bears effects of the minimum shareholding rules (Chou & Ko, 2014). Nevertheless, the results here imply low insider shareholding (high FIS) is linked with poor firm performance in OTC-traditional setting. Figure 1 synthesizes the empirical results of the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance. It shows a tendency that the entrenchment argument prevails in high-industry-complexity and large-firm-scale setting, while the convergence-of-interest argument prevails in low-industry-complexity and small-firm-scale setting. The empirical results in the remaining two settings are mixed and could be considered as gray areas. From the perspective of resource dependency theory, the tendency unveiled in Figure 1 is totally reasonable. According to resource dependency theory, bringing in “resources” to reduce environmental uncertainty is exactly the organizational function of boards. Firms in the high-industry-complexity and large-firm-scale 7 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 setting need more outsiders contribute their capital, knowledge and experience, access of information, social connections, legitimacy, and channels to all kind of other “resources.” It explains why a high insider ownership induces poor performance in this industrial setting. Conversely, in the low-industry-complexity and small-firm-scale setting, the needs of resource are easier to be satisfied by insiders. In this circumstance, the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance is more dominated by internal decision efficiency logic, hence the convergence-of-interest argument, rather than dealing with external uncertainty. Table 3: Effects of Insider Ownership on Firm Performance TSEC Companies Technological Industry Mode A Empirical Model (1): Mode B Traditional Industry Mode A Mode B Mode A 5.9776 (0.0000) *** -1.6516 (0.0025) *** ISD Technological Industry Mode B Traditional Industry Mode A Mode B 𝑬𝑷𝑺𝒊𝒕 = 𝜶𝒊𝒕 + 𝜷𝟏 (𝑰𝑺𝑹𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟐 (𝑰𝑺𝑫𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟑 (𝑭𝑰𝑺𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟒 (𝑫𝑼𝑨𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟓 (𝑳𝑬𝑽𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜺𝒊𝒕 -3.4229 (0.0022) *** ISR OTC Companies 9.4940 ( 0.0000) *** 1.2041 ( 0.0927) * 9.9342 ( 0.0000) *** 6.0918 ( 0.0006) *** 1.5757 ( 0.0137) ** FIS 0.0329 ( 0.5400) 0.0414 ( 0.4308) 0.2211 ( 0.0005) *** 0.1126 ( 0.0687) * 0.2293 ( 0.0000) *** 0.2340 ( 0.0001) *** -0.3971 (0.0008) *** -0.4286 (0.0006) *** DUA -0.2074 (0.3004) -0.1946 (0.3304) -0.2512 (0.0826) * -0.2169 (0.1446) 1.2227 ( 0.0002) *** 1.0588 ( 0.0003) *** -0.4038 (0.0284) ** -0.3870 (0.0573) * LEV -5.7713 (0.0000) *** -5.5237 (0.0000) *** -1.9885 (0.0000) *** -2.3085 (0.0000) *** -3.4731 (0.0012) *** -3.7869 (0.0003) *** -9.7717 (0.0000) *** -5.9960 (0.0001) *** Adj. R2 0.8903 0.9236 0.8977 0.8977 0.8356 0.8643 0.7721 0.7893 F 32.2029*** 47.4544*** 35.2701*** 35.2573*** 19.8591*** 24.6307*** 13.3281*** 14.6281*** D-W 2.2894 2.2996 2.2935 2.3219 2.4385 2.3730 2.2163 2.1823 Empirical Model (2): 𝑹𝑶𝑨𝒊𝒕 = 𝜶𝒊𝒕 + 𝜷𝟏 (𝑰𝑺𝑹𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟐 (𝑰𝑺𝑫𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟑 (𝑭𝑰𝑺𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟒 (𝑫𝑼𝑨𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜷𝟓 (𝑳𝑬𝑽𝒊𝒕 ) + 𝜺𝒊𝒕 -0.1835 (0.0000) *** ISR 0.3173 ( 0.0000) *** -0.0920 (0.0013) *** ISD 0.7020 ( 0.0000) *** 0.0625 ( 0.0000) *** 0.4937 ( 0.0000) *** 0.6192 ( 0.0000) *** 0.1604 ( 0.0001) *** FIS 0.0030 ( 0.2469) 0.0030 ( 0.2652) 0.0032 ( 0.0000) *** 0.0004 ( 0.1802) 0.0086 ( 0.0001) *** 0.0137 ( 0.0000) *** -0.0124 (0.0159) ** -0.0098 (0.0625) * DUA -0.0066 (0.5319) -0.0063 (0.5472) -0.0036 (0.0001) *** -0.0017 (0.0423) ** 0.0777 ( 0.0000) *** 0.0876 ( 0.0000) *** 0.0015 ( 0.7802) 0.0046 ( 0.3678) LEV -0.2490 (0.0000) *** -0.2368 (0.0000) *** -0.0598 (0.0000) *** -0.0639 (0.0000) *** -0.3457 (0.0000) *** -0.3544 (0.0000) *** -0.4758 (0.0000) *** -0.3215 (0.0000) *** Adj. R2 0.8098 0.8126 0.9324 0.8831 0.7822 0.7576 0.9520 0.9469 F 17.3684*** 17.6658*** 54.8526*** 30.4927*** 14.3310*** 12.5962*** 73.1788*** 65.8522*** 2.3759 2.3530 2.2471 2.2872 2.5257 2.4191 2.5018 2.4673 D-W This table shows the regression results based on Empirical Model (1) and (2). The number before the ( ) is the coefficient; the number within the ( ) 8 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 is the p-value. *, **, and *** denote the 10%, 5%, and 1% significant level respectively. In general, the results of the two empirical models are quite consistent, revealing that industrial settings do have impacts on the relationship between insider ownership and firm performance. In both empirical model, ISR and ISD have a positive coefficient with statistical significance in three of the four tested industrial settings (TSEC-traditional, OTC-traditional, and OTC-technological), implying the convergence-of-interests argument prevails in these industrial settings. However, the coefficients of ISR and ISD in TSEC-technological setting are negative with statistical significance results, implying a support for the entrenchment hypothesis in high complexity-large scale context. The empirical results on DUA show a different tendency between TSEC and OTC companies. All the 4 coefficients of DUA are negative for TSEC companies. Conversely, coefficients of DUA for OTC companies tend to be positive, with an exception from empirical model (1) for OTC-traditional setting. The empirical results on LEV are consistently negative for all the tested industrial settings. The empirical results on DUA show a different tendency between TSEC and OTC companies. For TSEC companies, all the 4 coefficients of DUA are negative, though only with statistical significance in traditional industry. Conversely, coefficients of DUA for OTC companies tend to be positive, with an exception from empirical model (1) for OTC-traditional setting. The empirical results on LEV are consistently negative for all the tested industrial settings, implying an inverse relationship between leverage and performance. Figure 1: Empirical Results in Different Industrial Settings 5. Conclusion This study examines the empirical relationship between insider ownership and firm performance in Taiwan, where the agency problem is typically the one of conflict interests between inside owners (inside directors) and outside shareholders. Based on the resource-based view (RBV) in strategic management field, this study argued that the relationship in concern may vary among different industrial settings. Through a two dimensions (scale, market-technology complexity) matrix, the four industrial settings were defined, and the convergence-of-interests and entrenchment hypotheses are tested via fixed effect panel regression models. The results show that, the convergence-of-interests argument was supported in three of the four industrial settings (TSEC-traditional, OTC-traditional, and OTC-technological) while the entrenchment argument got support in TSEC-technological setting, which means a high complexity-large scale context. Accordingly, this study inserts a new aspect in the related discussion, arguing that the positive convergence-of-interests effect and the negative entrenchment effect may co-exist in different industrial settings. This argument implies contextual-fitness must be taken into account in searching for effective 9 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 regulations of corporate governance. In addition, the results of this study could have an important implication on the widely adopted employee stock option plan, specifically the stock option and other equity-related items in executives’ pay packages. REFERENCE Barney, J.B. (2001) Resource based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource based view. Journal of Management, 27(6), 643-650. Barney, J.B. (1991) Firm resources and sustained competition. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. Berle, A.A. and Means, G.C. (1932) The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co. Bozec, Y., Rousseau, S., and Laurin, C. (2008) Law of incorporation and firm ownership structure: the law and finance theory revisited. International Review of Law and Economics, 28, 140-149. Chou, T. (2013) Effects of insider ownership on corporate governance in emerging market: Evidence from Taiwan. Global Journal of Business Research, 7(3), 47-58. Chou, T. and Ko, P. (2014) The Relationship between the Minimum Shareholding Requirements and Investor’s Risk. Commerce and Management 15(2). (forthcoming) Claessens, S., Djankov, S., and Lang, L. (2000) The separation of ownership and control in East Asia corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 81-112. Davies, J.R., Hillier, D. and McColgan, P. (2005) Ownership structure, managerial behavior, and corporate value. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11, 645–660. Delios, A., Zhou, N. and Xu, W.W. (2008) Ownership structure and the diversification and performance of publicly-listed companies in China. Business Horizons, 51, 473-483. Demsetz, H. and Lehn, K. (1985) The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1155-1177. Demsetz, H. and Villalonga, B. (2001) Ownership structure and corporate performance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 7, 209–233. Donnelly, R. and Kelly, P. (2005) Ownership and board structures in Irish plcs. European Management Journal, 23(6), 730-740. Faccio, M., and Lang, L. (2002) The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65, 365-395. Fama, E.F. and Jensen, M.C. (1983) Separation of ownership and control. Journalof Law and Economics, 26, 301-325. Garcia-Meca, E. and Sanchez-Ballesta, J.P. (2011) Ownership structure and forecast accuracy in Spain. Journal of International Accounting Auditing and Taxation, 20, 73-82. Gugler, K., Mueller, D.C. and Yurtoglu, B.B. (2008) Insider ownership, ownership concentration and investment performance: An international comparison. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14, 688-705. Hermalin, B.E. and Weisbach, M.S. (1991) The effects of board composition and direct incentives on firm performance. Financial Management, 20, 101-112. Hung, J.H. and Chen, H.J. (2009) Minimum shareholding requirements for insiders: Evidence from Taiwanese SMEs. Corporate Governance, 17(1), 35-46. Jensen, M.C. (1986) Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76, 323-329. Jensen, M.C. and Ruback, R.S. (1983) The market for corporate control: The scientific evidence. Journal of Finance Economics, 5(11), 5-50. Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H. (1976) Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and 10 Proceedings of 9th Annual London Business Research Conference 4 - 5 August 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-56-6 ownership structure. Journal of Finance Economics, 3(4), 305-360. Kearney, C. (2012) Emerging market research: Trends, issues and future directions. Emerging Markets Review, 13, 159-183. La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., and Shleifer, A. (1999) Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471-518. Leask, G., and Parnell, J.A. (2005) Integrating strategic groups and resource based perspective: Understanding the competitive process. European Management Journal, 23(4), 458-470. Lins, K.V. (2003) Equity ownership and firm value in emerging markets. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38(1), 159–84. McConnell, J.J. Servaes, H. and Lins, K.V. (2008) Changes in insider ownership and changes in the market value of the firm. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14, 92-106. Morck, R., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1988) Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 293-315. O’Regan, N., Sims, M. and Ghobadian, A. (2005) High performance: Ownership and decision-making in SMEs. Management Decision, 43(3), 382-396. Palia, D. and Lichtenberg, F. (1999) Managerial ownership and firm performance: A re-examination using productivity measurement. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5, 323-339. Park, K. and Jang, S. (2010) Insider ownership and firm performance: An examination of restaurant firms. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29, 448-458. Patro, S. (2008) The evolution of ownership structure of corporate spin-offs. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14, 596-613. Peteraf M.A. (1993) The cornerstones of competitive advantage: a resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179-191. Roosenboom, P. and Schramade W. (2006) The price of power: Valuing the controlling position of owner-managers in French IPO firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12, 270-295. Sanchez-Ballesta, J.P. and Garcia-Meca, E. (2007) A meta-analytic vision of the effect of ownership structure on firm performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(5), 879-893. Sheu, H.J. and Yang C.Y. (2005) Insider ownership structure and firm performance: A productivity perspective study in Taiwan’s electronics industry. Corporate Governance, 13(2), 326-337. Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1997) A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52, 737-783. Taboada, A.G. (2011) The impact of changes in bank ownership structure on the allocation of capital: International evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35, 2528-2543. Tsai, W.H., Hung, J.H., Kuo, Y.C. and Kuo, L. (2006) CEO tenure in Taiwanese family and non-family firms: An agency theory perspective. Family Business Review, 19(1), 11–28. Wernerfelt, B. (1984) A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180. 11