Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference

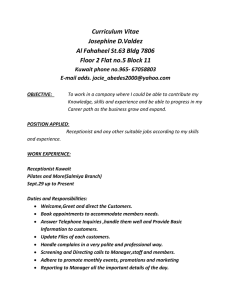

advertisement

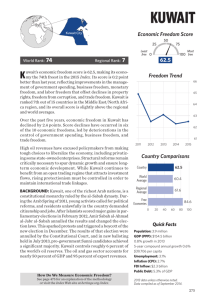

Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 The Adverse Impact of the Structural Economic Imbalances in the State of Kuwait Mohammad Ramadhan1 The State of Kuwait is a small, rich, oil-based economy with an estimated GDP of 183 US$ bill in 2014. The economy depends heavily on oil exports revenues, which account for 58% of GDP, 95% of exports, and 94% of government income. The economy is characterized by the dominance of the large public sector in major economic activities. Such prolonged unwarranted structure has adversely affected non-oil GDP growth, limited the job opportunities for nationals, and resulted in severe structural economic imbalances. The main structural imbalances of Kuwait’s economy can be summarized as the following: dominance of the public sector over the private sector; heavy dependence of national income and aggregate exports on oil; limited share of the private sector in the GDP; dichotomy in the labor market with high concentrations of national labor in the public sector (disguised unemployment), while the expatriate labor is deeply concentrated in the private sector; rigid spending pattern of public budget and dependency on oil revenues; imbalanced population structure with the number of expatriates being more than twice the number of nationals. This paper provides an overview of Kuwaiti economy in terms of economic structure and indicators. The magnitude of structural imbalances was examined in detail to assess their negative economic impact. The paper proposed a strategic framework for an overall economic reform to rectify the persistent structural imbalances. Within this context, it is important to review recent public policies and new laws initiated by Kuwait’s government in addressing the structural imbalances. Key words: Kuwait, structural imbalances, labor market, public sector, private sector, strategic framework. Field of Research: Economics JEL Codes: E62 and J21 1. Introduction Kuwait is a small, rich economy with abundance in crude oil that is entirely owned by the state. Due to unprecedentedly high oil exports and revenues, total nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew substantially to US$ 198.03 bn in 2013. Kuwait's oil and non-oil GDP accounted for 55.9% and 44.1% of total nominal GDP in 2013, respectively. Moreover, oil revenues accounted for around 96% of exports and 94% of government income. Escalating government expenditures have resulted in high standards of living and one of the highest per capita in the world estimated at $48,900 in 2012 (CSB 2013). Kuwait's economy can be characterized by the dominance of the public sector and heavy dependence on oil exports both in terms of the generated value added and 1 Dr. Mohammad Ramadhan, Research Scientist at Techno Economic Division, Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, Kuwait Email: mrammad@yahoo.com Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 revenues. The government of Kuwait in its efforts to share the oil wealth with citizens has adopted an extensive welfare-oriented approach toward development. The development of Kuwait has tremendously depended on public policies geared toward heavy government spending. Consequently, such public policies have led to the dependence on the government for the provision of employment and most social services (Ramadhan et al. 2013). Such dependence has created prolonged structural imbalances that include among others: Overwhelming contribution of the public sector to GDP. Limited share of the private sector in major economic activities. Dependency of government revenues on a single source of income (oil and other hydrocarbon products). Labor market dichotomy, with the national labor force concentrated in the public sector, and the expatriate labor force work dominating the private sector. This paper intends to address the adverse impact of the structural imbalances on Kuwait’s economy. The paper will proceed in the following structure. Section two will present the theoretical background on the role of the public sector in economic growth. Section three will present an overview of the Kuwaiti economy in terms of economic structure and indicators, and will evaluate the magnitude of structural imbalances and assess their negative economic impact. Section four will propose a strategic framework to rectify the persistent structural imbalances and provide the basis for an overall economic reform. Section five will review recent public policies and new laws initiated by Kuwait’s government in response to the structural imbalances. Finally, conclusions and recommendations will be presented in section six. 2. Review of Literature The most eminent of Kuwait’s structural imbalances is the role of the large public sector in redistributing the wealth generated from oil revenues through the comprehensive welfare system. The main argument to be raised is should the government reduce the size of the inefficient public sector in economic activities for a more vibrant role of the private sector? Will the growth and expansion of the private sector have a positive impact on the economy in terms of long-run output and employment? There is an extensive theoretical and applied literature regarding the relationship between the size of the public sector and the rate of economic growth. Mavrov (2007) showed that economies controlled entirely by governments (public sector) have witnessed relatively low level of economic growth. This is due to the fact that most economic decisions are controlled entirely by governments with the absence of the private sector interest. This argument presents an important concern regarding the appropriate size of the public sector that leads to optimal economic growth (Ramadhan et al. 2014). Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Empirical literature conducted on the public sector’s size and role has two opposing views. Ram (1989) indicated that economic growth can be stimulated by large government size. On the other hand, many scholars contradicted this view and indicated that as the government size increases, in the relative term, it reduces the growth of per capita income (Barro 1991, Bairam 1990, and Grossman 1990). Nonetheless, Husnain (2011) pointed out that within these mixed findings, a consensus emerges that up to a certain level, government activities can stimulate growth, but beyond this level, the size of government may reduce economic growth. Husnain attempted to determine the optimal size of government in Pakistan for the period 1975-2008; his findings showed that government size is optimized when public expenditures reach 21.5% of GDP. Kuwait more or less depicts a growth model similar to Barro’s endogenous growth framework that allows government expenditure to increase economic growth through the provision of public services that can be used as an input to private sector production (Barro 1990). However, Barro noted that government expenditure crowds out more productive private investment, and hence, can affect the growth rate negatively in the long run. More importantly, Barro (1991) examined the issue of the optimal share of public sector in the economy by analyzing the public share of 98 countries. He identified a significant inverse relationship between the share of public sector in GDP and GDP growth. He concluded that the average share of public sector in these economies was around 20%. As a proxy, this estimated threshold size is far lower than the current share of Kuwait’s public sector in GDP (70%). In a nut shell, given the inefficiency of Kuwait’s public sector, ineffective utilization of resources, and persistence of the structural imbalances, it is safe to assume that Kuwait’s economic growth rate would increase if public sector’s size and expenditures were to be reduced. 3. Major Structural Imbalances The recent Global Competitiveness Index for the fiscal year 2014-2015 confirmed that Kuwait dropped to the 40th ranking from the 35th ranking in the fiscal year 2010-2011. Other GCC members (UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia) achieved higher rankings at 12th, 16th and 24th, respectively. This indicates that Kuwait faces many problems and challenges that impede its economic development. Most of the economic problems stem from the imbalanced structure of the economy. The following subsections will shed light on the nature and magnitude of the major imbalances and assess their negative economic impact. 3.1 Expenditures on GDP and Dependency on Oil Kuwait economy is characterized by the dominance of the public sector and heavy dependence on oil both in terms of the generated value added and revenues. Table 1 presents expenditure components of Kuwait's GDP over the period 20102013. In 2013, the total nominal GDP was around US$ 198.03 bil with minimum growth from previous year. Yet, a 57% contribution was registered for the oil sector compared to 16.9% for non-financial services. Remaining activities’ share Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 was minimal (6.8% for manufacturing industries, 6.5% for financial services, 3% for wholesale and retail, and 5% for transport storage and transportation). During the oil boom period (1976-1982), Kuwait enjoyed huge surpluses in its public budget and balance of payments. Yet, most of the financial surpluses fled the country in the form of investments in income-producing assets abroad. This supported the widely held view that Kuwait has a limited absorptive capacity, since it was unable to utilize these gains internally without adversely affecting its macroeconomic stability (Ramadhan et al. 2013). However, the fiscal situation had changed radically following the downturn in oil prices in late 1982, leading to real budget deficits over the period 1983-1989. The Iraqi invasion in August 1990 reinforced this trend, which resulted in both internal and external deficits. For the five years prior to the financial crisis of 2008, the economy benefited from the drastic increase in global demand for oil. The sharp increase in oil revenues over the period 2004-2008 created huge internal and external surpluses, causing the economy to grow at a high average rate of 23.1% per annum. Such a high growth rate indicated the overwhelming dependency of its economy on the revenues generated from oil. However, the sharp decline in oil revenues in 2009 reduced these surpluses drastically. Moreover, the current and expected increases in government spending should limit surpluses to a much lower levels than those witnessed in the previous boom years. Since the global financial crises of 2008-2009, the GDP grew by 12.8% per annum over the period 2010-2013. It should be noted, however, that any noticeable decline in the relative importance of the oil GDP was mainly due a slump in oil prices and the reduction in export volume rather than due to a substantial real growth of the non-oil sector. Expenditures on GDP during this period (Table 1) revealed that the two main components of aggregate demand, namely government consumption and private consumption, have increased from the values of US$ 19.76 bn and US$ 33.32 bn respectively in 2010 to the values of US$ 29.57 and US$ 42.74 bn respectively in 2013. The same trend could be noticed with net exports. However, gross capital formation component of aggregate demand increased slightly from the value of US$ 18.49 bn in 2010 to US$ 23.14 bn in 2013. The fact that the public sector is responsible for the execution of the major part of the investment activities would indicate that slow spending on investments (capital formation) on the part of the government would have an obvious indirect impact on the performance and growth of the private sector. However, investments demand is an important economic indicator of the economy’s ability to sustain long-term growth. Consequently, severe fluctuations in aggregate investments in Kuwait over the years could indicate the vulnerability of the local economy to sustain long-term growth. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Table 1: Kuwait Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by Expenditure Indicator 2010 2011 2012 2013 Oil GDP 64.45 97.79 113.79 110.64 Nonoil GDP 66.53 74.75 81.09 87.39 GDP 130.97 172.54 194.89 198.03 Per Capita GDP (Value in 1000$) 36.56 46.67 50.97 49.94 Government Consumption 19.76 22.93 26.22 29.57 Private Consumption 33.32 37.36 41.18 42.74 Gross Fixed Capital Formation 18.49 19.91 21.11 23.14 Net Export 35.01 39.90 45.75 46.67 Total Expenditure on GDP 115.34 154.06 174.08 175.79 Expenditure on GDP Source: Central Statistical Bureau, Annual Statistical Abstract, 2013. (Values in Bill US$) 3.2 Limited Role of the Private Sector Structural imbalances have adversely limited the role and contribution of the private sector in economic activities. This fact has detrimental impact on the sustainability of long-term economic growth. An analysis of the private sector’s role in economic activities revealed that the private sector has dominated the majority of the non-oil activities. However, the contribution of most of these activities to the GDP and non-oil GDP is minimal, except for the three main activities of finance, insurance, real estate and business services; transport, storage and communications; and wholesale and retail trade, hotels, and restaurants. The combined contribution of these three non-oil activities was around 30.93% of the total GDP, or alternatively 56.90% of the non-oil GDP. Furthermore, over the period 1997-2001, the share of the private sector in GDP and non-oil GDP averaged around 24.5% and 44.1%, respectively. However, due to the rise in oil prices and the spillover effect of increased government spending over the period 2001-2013, the share of the private sector in GDP has averaged around 31.4% (CSB, 2013). The drastic rise in oil prices since 2002 and, subsequently, the sharp rise in Kuwait oil revenues have accelerated the nominal GDP growth. However, this unprecedented growth has adversely affected the Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 non-oil sectors of the economy. The oil sector remains dominant in the economy and has substantial indirect effects on the non-oil sectors. The public spending funded by oil revenues remains essential to private sector’s various economic activities. Table 2. Share of Private Sector in Gross Domestic Product Indicator 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013* GDP 36.2 57.6 119.8 131.0 198.0 Oil GDP 15.0 26.6 60.1 64.4 110.6 Nonoil GDP 21.3 31.0 59.7 66.5 87.4 Private Sector (PS) 8.9 18.9 40.0 41.6 62.3 Share of PS in GDP 24.70% 32.90% 33.40% 31.80% 31.45% Share of PS in Non-oil GDP 42.08% 61.16% 67.05% 62.61% 71.27% Source: Central Statistical Bureau, Annual Statistical Abstract, 2005, 2013. (Values in Billion US$) * The Share of PS in GDP was estimated by calculated the average PS share from 2001 to 2010. 3.3 Rigid Structure of Public Finance Table 3 presents the main components of public budget for the last five fiscal years (2009/2010 - 2013/2014). Government spending in fiscal year (FY) 2012/2013 reached a historical high level at US$ 68.3 bn, around 74.1% increase from the FY 2009/2010 budget of US$ 39.2 bn. Government spending in FY 2013/2014 was slightly lesser from previous year, yet it was at the higher end at US$ 66.45 bn. Over the five-year period, government expenditure was increasing rapidly at around 18.5% per annum. The massive rise in spending was forced by the hikes in salaries, grants, and transfer payments. Total government revenues were estimated at US$ 113.3 bn, with oil income constituting 93.6% of total revenues. More importantly, the primary budget surplus peaked at US$ 47.25 bn in 2011/2012, and averaged around US$ 35.83 bn for the period. In fact, the last 13 public budgets have all posted surpluses in public budgets. Expenditures in Kuwait’s public budget are classified into five chapters (categories). For FY 2013/2014, the expenditures were as follows: salaries US$ 17.71 bn, commodities and services US$ 11.32 bn, transports, machinery and equipment US$ 0.74 bn, construction, maintenance and public acquisitions US$ 5.38 bn, and miscellaneous expenditures and transferable payments US$ 31.31 bn. Expenditures on chapters one and five, i.e., salaries and transfer payments Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 (subsidies for electric and water, health, education) constituted around 74% of total public spending. Disturbingly, spending on salaries and transfer payments have almost doubled over that period. In contrast, the high spending on wages and subsidies overshadows spending on capital investment and developmental projects. i.e., investments on construction projects and maintenance constituted only 8% of the total expenditures. While one can look favorably at the surpluses of Kuwait’s public budget, trade balance, current account balance, and absence of public debt, the fact that the budget revenues are heavily dependent on oil income emphasizes its high sensitivity to fluctuation in oil prices. Hence, sustaining a balanced budget in the absence of other sources of income (no tax income) requires high oil prices at all times. The dependency on oil revenues also raises the concern on the future strains that these expenditures will have on the public budget in the light of government’s lack of efforts to diversify the economy sources of income. Moreover, it should be emphasized that expenditures on capital formation has lagged behind over the years. Within the context of previous underinvestment, it is necessary that capital spending increases considerably in order to energize the private sector role in the economy (Hertog 2012). Within the context of the bureaucratic and inefficient public sector in the state of Kuwait, the government of Kuwait should energize the role of the private sector in the economy by reducing its role, which includes privatization of some of these State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Table 3. Kuwait’s Public Budgets for (FY 2010/2011 - FY 2013/2014) FY 2010/11 FY 2011/12 FY 2012/13 FY 2013/14 Expenditures 58.76 60.75 68.33 66.45 Salaries 12.40 14.66 17.10 17.71 Commodities and Services 10.11 9.86 12.88 11.32 Transport, Machinery and Equipment 0.55 0.52 0.56 0.74 Const., Main. and Public Acquisitions 6.11 5.90 5.85 5.38 Miscellaneous Exp & Transfer payments 29.58 29.81 31.94 31.31 Revenue 77.89 108.00 113.27 111.82 Oil Income 72.26 102.05 106.06 102.96 Nonoil Income 5.63 5.95 7.22 8.86 Primary Surplus/ (Deficit) 19.13 47.25 44.95 45.37 Reserve for Future Generations 7.79 10.80 28.32 27.95 Final Surplus/ (Deficit) 11.34 36.45 16.63 17.42 Source: Ministry of Finance, General Accounting Affairs Guidance & System Department, Kuwait, 2011-2012, 2012-2013, 2013-2014. (Values in Billion US$). 3.4 Dichotomy in the Labor Market The labor market in Kuwait is severely unbalanced; Table 4 explains the dichotomy in the labor market in 2014. Analysis of labor data revealed the following astonishing facts: Total labor force was estimated at 2.45 million, where private sector represents 80% of total jobs, while the public sector represents only 18% of the total. National labor constituted only 17% of total, while expatriates dominated the labor market with 83%. 75% of the national labor force is employed in the public sector, while 80% of the expatriates labor force is employed in the private sector. The public sector is dominated by Kuwaitis (71%), while the private sector is dominated by non-Kuwaitis (95%), with Kuwaitis representing only a low 5% of total employment in this sector. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 The size of non-Kuwaitis in the public sector (133,886) exceeds the size of Kuwaitis in the private sector (91,182). The dichotomy in the labor market structure highlights many adverse consequences on many aspects of the economy. Firstly, the excessive employment of national labor force in public sector leads to disguised unemployment, i.e., employing Kuwaitis in highly paid unproductive jobs with no apparent value added. More importantly, expenditures on the increasing number of highly paid jobs for nationals is putting a real pressure on the public budget, and in the light of declining oil prices this will lead eventually to a deficit. Secondly, the private sector share in the economy is limited only to 35%, while total employment in the private sector is around 1.96 million (80% of total employment). This raises a fundamental concern that of whether the economy really needs around 2 million expatriates that contribute minimally to output. This fact indicates that most of the expatriates are employed in low paid and inefficient jobs with no productivity or value added. More importantly, the large expatriate’s labor force consumes large amount of the public subsidized services (electricity, water, health, education, roads, etc.), which exert enormous pressure on the fragile public budget. Hence, major labor market reform is well needed to tackle the unbalanced labor market. Table 4. Labor Force in Kuwait (2014) Sector Kuwaitis % of Kuwaitis by NonTotal Labor Kuwaitis Force % of NonKuwaitis by Total Labor Total Labor Force Force % of Total Labor Force Public 320,140 71% 133,886 29% 454,026 100% Private 91,182 5% 1,870,830 95% 1,962,012 100% Unemployed 11,003 27% 29,557 73% 40,560 100% Total Labor Force 422,325 17% 2,034,273 83% 2,456,598 100% Source: Public Authority for Civil Information, Population and labor force Bulletin, December 2014. 4. Strategic Framework for Economic Reform Many prominent scholars and research institutions have addressed the importance of addressing and resolving Kuwait’s structural imbalances. Previous studies conducted such as KISR/ CMT on the Financial Sector of Kuwait (1988), World Bank report on Energizing Private Sector in Kuwait (2001); McKenzie report on Financial & Economic Reform in Kuwait (2007), Blair report on Kuwait’s Vision 2035 (2009), KISR report on Strategy for Private Sector Development in Kuwait (2012) have emphasized the urgent need for economic and labor reform in Kuwait. Due to the fact that most of structural imbalances are resulting from the dominance Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 of the public sector in economy, economic reform should focus and be directed toward the utilization of public sector capabilities, operations, and initiatives to deliver synergetic solutions to the causes of the inefficient public sector, also, to create conducive environment that enables the private sector to play a more active role in economic activities by eliminating problems and obstacle that impedes its growth. Within the context of supporting public sector initiatives and private sector operations, economic reform should be centered on the following thrusts: Improving the business environment Increasing aggregate investments Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) Privatization Increasing the role of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Kuwait. Formulation and implementation of economic reform in Kuwait entails a multidimensional approach. The current rates of investments in Kuwait are very low, consistent with Kuwait’s steady but quite slow non-oil economic growth in the last two decades. At the same time, the economy generates a gross savings rate substantially higher than its rate of investment, a situation that results in reserve accumulation and massive capital outflows. The capital outflows are a mix of portfolio investment, FDI in various countries, and the accumulation of foreign bank account holdings. Meanwhile, FDI in Kuwait itself currently stands at a miserably low level. Turning this situation around presents an enormous challenge for Kuwait, i.e., keeping in mind the objective of creating a strong private sector that will employ nationals (entrepreneurs and labor) and gradually reducing dependence on expatriates. Hence, the proposed strategic economic reform highlights a range of possible approaches that emphasize the rationale for the aforementioned strategic thrusts. The envisaged approaches can be summarized in the following discussion: First Approach: It is very significant and crucial that Kuwait should be implementing, as rapidly as it reasonably can, the regulatory and business environment improvements. Such improvements will create better conditions for all new businesses starting up in the country, as well as for the existing ones; and it will also facilitate higher volumes of investment, both by existing firms, government agencies and publicly owned firms, and incoming investors (FDI). Second Approach: Investment is important in promoting long-term economic growth. Steady and strong economic growth can facilitate a bigger role for the private sector in the economy. However, there is the critical question of how to raise the volume of investment in Kuwait, whether of domestic origin or funded through FDI, to achieve the targeted GDP growth rate. In order to meet its medium- term and longer-term employment objectives, the economy of Kuwait clearly needs to be growing more rapidly than it has even done over the past two decades. Third Approach: Kuwait should also be taking action to adopt and implement policies and regulatory changes to facilitate and promote FDI. FDI tends to be accompanied by significant benefits for the domestic economy in terms of Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 management expertise, access to markets and market networks, innovation and new technology, knowledge of modern business methods, skills development and training programs. In particular, for a small economy such as that of Kuwait, these are extremely important benefits. Moreover, the benefits for Kuwait can be enhanced if FDI projects were to be undertaken in ways that do not result in ‘foreign enclaves’ within the domestic economy. In other words, FDI is most beneficial when there are strong upstream and downstream linkages with the domestic economy, where personnel move between domestic firms and the businesses funded through FDI, and where knowledge transfers and effective learning are facilitated. Fourth Approach: Privatization is an important economic/political tool that a country can implement in order to rectify economic imbalances created by the dominance of public sector and to speed up economic growth. Privatization entails the transfer of public entities/projects to private firms. However, there are certain prerequisites that need to be met for effective implementation of privatization process. The most significant of these prerequisites is the provision of an environment that is conducive in promoting effective large-scale private sector engagement in economic activities. The enabling environment includes infrastructure, legislation, regulation, and ease of doing business. Therefore, the scope of privatization covers ceding of government control of economic entities and projects to private firms, attracting strategic investors both domestic and foreign, encouraging private investments, attracting FDI, and promoting and enabling friendly business environment. Within the context of Kuwait economy, the drive behind all these factors is to increase the competitiveness and productivity of the economy. 5. Recent Economic Laws In response to the negative affect of the persistent structural imbalances on the performance of Kuwait’s economy, and in the efforts to revert the decline of Kuwait’s ranking in all global and regional indices, the government has (recently) passed new laws and initiated a few programs to address and tackle the challenges presented by these imbalances. The targets of these new laws and initiatives have been discussed in detail in the major studies conducted by leading research think tanks. Hence, the new laws and initiatives aimed to overcome the public sector’s large size and inefficient utilization of resources, and to promote a vibrant role for the private sector by improving the business environment. The following sub sections will present the important laws and discuss their objectives. Law No. 37/2010 Concerning the Regulation of Privatization Programs and Operations. The most important step in Kuwait’s privatization initiative was the declaration of the law 37/2010 for regulating the privatization program and operations. Subsequently, the Supreme Council for Privatization (SCP) was established in May 2012 by the Amiri Decree 106/2012 for the purpose of executing and implementing the law. The newly born SCP faces many challenges that include selecting the Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 appropriate method of privatization for each project relative to the operating conditions and requirements of specific sector, formulating a comprehensive legislative and organizational framework to support the privatization process, and protecting the interest and rights of all concerned parties involved in the process (government, investors, consumers, workers, citizens). The main objectives of Kuwait's privatization program can be summarized as the following: Increase the role of the private sector in economic activities. Enhance the competitiveness of the local economy. Attract local and foreign direct investments. Assist in developing capital markets. Build a friendly business environment. Provide a fair distribution of national wealth among citizens. Protect and rehabilitate national labor. Prepare the private sector to absorb a fair share of the national labor force. Enhance the overall state public budget. Protect the local environment. Law No. 98/2013 for Establishing the National Fund for the Promotion and Development of Small and Medium Enterprises. National Fund for the Promotion and Development of SMEs was established in April 2013 with a capital of KD 2 billion (about US$ 7 billion). Unlike its predecessor, the fund will provide access to finance to promising initiatives without any interference in the management of the financed projects. Generously, the SMEs fund will provide land, a true scarce resource for investors in Kuwait. It is also mandated to build and operate incubators in several districts within Kuwait. Finally, its business processes are subject to reasonable time limits required to facilitate the infant project’s dealings with government approvals and licenses and within pre-assigned time limits. The SMEs Fund’s priorities are set in the law: the first priority goes to projects that maximize the value added, diversify the economy and create jobs for nationals, followed by stimulating innovations, promoting selfemployment spirit, using locally produced goods, and employing environmentfriendly technologies. A significant feature in the law is its intended plan to make the SMEs Fund as the central focus of government support to SMEs at the national level. As such, the Fund is decreed to coordinate, customize, and institute a sustained model of support for all SMEs, especially startups without the multiplicities, conflicts, and wasted efforts and resources. Law No. 116/2013 for Establishing Authority Investments in Kuwait for Promoting Direct This new law will repeal predecessor Law No. (8) of 2001 regarding the Regulation of Direct Investment of Foreign Capital in the State of Kuwait. Consequently, the Kuwait Foreign Investment Bureau (KFIB) will cease to exist. All KFIB assets, liabilities, obligations and decisions will be transferred to the new authority, which will be established under the new law as Kuwait Direct Investment Promotion Authority (KDIPA). The law will come into force six months from the date of Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 issuance. The new law is a an important addition to a host of new economic laws and regulations that have been recently approved for the purpose of improving the overall investment climate, fostering competitiveness, encouraging more engagement in value-added investment opportunities by both local and foreign investors, and contributing to achieve the country's economic and social objectives. Under the new law, investment entities can take three distinct forms: a Kuwaiti company in accordance with the new Decree Law No. (25) of 2012 regarding the Companies Law as amended by Law No. (97) of 2013 with up to 100% foreign equity; or operate as a licensed branch of a foreign company; or introduced for the first time under the new law to establish a representative office to exclusively conduct marketing studies without engaging in a commercial activity or activity of commercial agents. The law adopts the "one-stop shop" approach overseen by an administrative unit within the authority in coordination with the relevant government authorities, to complete procedural steps within the timeframe mandated by the law (www.kfib.com). Law No. 24/2012 Establishing the Public Authority for Combating Corruption and Provisions for Financial Disclosure The Kuwait Anti-Corruption Authority was founded by an Amiri decree to fight and prevent corruption, and address its causes. Its other tasks include prosecuting perpetrators; recover funds and proceeds of corruption; promote the principle of cooperation and join the state and regional and international organizations in the field of anti-corruption; administrate the principle of transparency and integrity in economic, financial and administrative transactions, activate the principle of equality; promote the supervisory role of competent bodies; protect state institutions and agencies from manipulation, exploitation and the abuse of authority for personal benefit; prevent mediation and nepotism that revoke a right or realize a wrong; encourage the role of institutions and organizations of the civil society in an effective and operative participation in the fight against corruption. The authority aims to establish the principle of transparency and integrity in financial and administrative transactions to ensure the realization of good governance of funds, resources, and state property and their optimal use (Times 4014). These were the most important laws and initiatives enacted by the government in response to the main economic challenges. Two more important laws were also passed in accordance with the aforementioned laws. Law No. 25/2012 for Issuing New Companies aimed to energize the role of the private companies in economic activities by addressing some of the issues that hinder their performance and contribution. Law 10/2007 for Protection of Competition aimed to tackle the monopolistic and oligopolistic structure prevalent in many economic sectors in Kuwait. It should be noted, however, that while the initiation of these laws is a positive step in tackling some of the structural imbalances in private sector development, the government is very slow in establishing the administrative and operational structure of these organizations. In most cases, these new entities are struggling to put forward a competitive organizational structure that can execute the objectives stated in its mandates. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 6. Conclusions and Recommendations This paper has examined in detail the main structural imbalances that Kuwait faces, and assessed its adverse impact on the Kuwaiti economy. The paper has also provided the framework guidelines for the economic reform needed to tackle the economic challenges. The government’s recent initiatives to address these imbalances and challenges were highlighted. The most imminent of the challenges facing Kuwait, however, is how to sustain high income levels for future generations, acknowledging that the present generation is characterized by high consumption behavior, dependency on state resources (wages and subsidized services), and low productivity in terms of value added. This entails the formulation of public policies with clear strategies and objectives for the transformation of Kuwait’s economy to a productively diversified economy that is less dependent on oil. The objective of the transformation process is to expand and diversify the production base of Kuwait’s economy in order to include more economic activities in services and manufacturing, led by a prudently regulated private sector. This will enhance job opportunities for the increasing number of young nationals entering the labor market. The formulation of the transformation strategy must emphasize reform actions and measures that can rectify the current imbalances in the economy and provide a road map to an efficient and rather diversified economy. The paper proposed strategic economic reforms focusing on possible strategic thrusts and economic tools. The most important of these tools and initiatives include privatization, improving business environment, promoting local and foreign investments, and bolstering SME’s growth. Reform measures may include among others the following: corporate taxes, imposition of users' fees, activation of necessary economic laws and initiatives, imposition of fees on expatriate labor, and, most importantly, active private sector development. References Bairam, E. 1990 ‘Government Size and Economic Growth: The African Experience 19601985’, Applied Economics, 22, 1427-1435. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00036849000000113. Barro, R.J. 1990 ‘Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth’, Journal of Political Economy, 98, 103-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/261726 Barro, R. 1991 ‘Economic Growth in a Cross-Section of Countries’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 407-443. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2937943. Bennett, J., Estrin, S. and Urga, G. 2007 ‘Privatization Methods and Economic Growth in Transition Economies’, Economics of Transition, 15, 661683. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2007.00300.x Blair Report, 2009 ‘Kuwait's Vision 2035’, for the Amiri Diwan, the State of Kuwait. Central Statistical Bureau (CSB). 2013 ‘Annual Statistical Abstract’, the State of Kuwait. Grossman, P.J. 1990 ‘Government and Growth: Cross-Sectional Evidence’, Public Choice, 65, 217-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00204946 Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Hertog, Stephan. 2012 ‘Towards new arrangements for state ownership in the Middle East and North Africa’. Originally published in Amico, Alissa, (ed.) OECD, London, UK, pp. 71-92. Husnain, I. 2011 ‘Is the Size of Government Optimal in Pakistan?’ Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 12, No. 2. KISR/CMT 1988 ‘The Financial Sector of Kuwait: Present Structure and Prospects for Future Development’ ,prepared jointly by KISR with Harvard/MIT universities for the Ministry of Finance, the State of Kuwait. McKenzie Report, 2007 ‘Financial and Economic Reforms in Kuwait’, for the Council of Ministers, the State of Kuwait. Mavrov, H. 2007, ‘The Size of Government Expenditure and the Rate of Economic Growth in Bulgaria’, Economic Alternatives, 1, 52-63. Ramadhan, M. and Al-Musallam, M. 2014 ‘The International Experience in Private Sector Development: Lessons for Kuwait’, Theoretical Economics Letters, 4, 279-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2014.44038. Ramadhan, M., Hussain, A., Hajji, R. 2013 ‘Limitations of Kuwait's Economy: An Absorptive Capacity Perspective’, Modern Economy, 4, No 5, 412-417 Ram, R. 1989 ‘Government Size and Economic Growth: A New Framework and Some Evidence from Cross-Section and Time-Series Data’, The American Economic Review, 79, 218-284. Times 2014 ‘New Authority to Monitor Official Corruption’ Weekly Magazine, Issue No 723, 28/12/2014, accessed at www.timeskuwait.com. World Bank 2001 ‘Energizing the Private Sector in Kuwait’, study in collaboration with Kuwait University (2001), for the Supreme Planning Council, the State of Kuwait.