W a s t e C o m... S u m m a r y o...

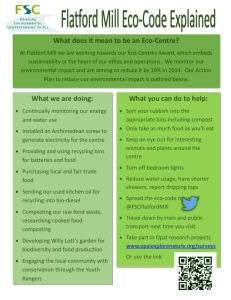

advertisement