The Martial Arts of Renaissance ... and London: Yale University ...

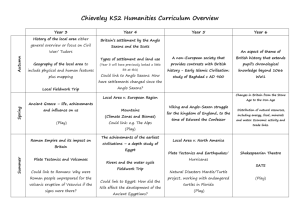

advertisement

Sydney Anglo, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000), xii + 384pp., 192 b&w and 28 colour illustrations, ISBN 0300083521 Sydney Anglo’s history of the martial arts in Renaissance Europe takes as its starting point the following premise: ‘While nobody has ever doubted the importance of expertise in the handling of weapons to the knightly classes of medieval Europe, our knowledge of what these skills were and how they were acquired remains generalized and inexact. More remarkably, the same holds true of the Renaissance when, despite the constant reiteration by humanist educational theorists of the value of training the body as well as the mind, we still know next to nothing about the practice of physical education and the provision of combat training for youths.’ Anglo’s stated aim is to fill this gap in our collective knowledge—in short, ‘to establish the martial arts within the broader contexts of intellectual, military and art history while establishing more precisely what these activities were, and how they were systematized.’ With that in mind, he prefaces his study with two caveats: first, that his temporal definition of the Renaissance is a broad one; and secondly, that he offers no discussion of pistols or guns because Renaissance writers of treatises on combat did not consider such weapons sufficiently sophisticated to bother commenting on them. This book, Anglo suggests, ought to be regarded not as a definitive, encyclopaedic study, but rather as an ‘experimental essay’. Anglo vividly re-creates the world of Renaissance arms and armour by surveying a wide variety of sources drawn from nearly every corner of Europe: France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Germany, the Low Countries, and England all feature prominently in his study. Anglo analyses extant pieces of arms and armour as well as a variety of written sources, both in manuscript form and in print. These include treatises on combat, educational manuals, courtesy books, and legal documents. In discussing the written sources, Anglo is attentive both to language and rhetoric and, where appropriate, to the visual impact of explanatory illustrations and diagrams (more than 200 of which are beautifully reproduced in this book). However, all of these sources—as Anglo frequently notes—are possessed of severe limitations. Because the martial arts were such an integral part of Renaissance life, relatively few writers seem to have felt the need to offer a thorough explication of the subject matter—or, as an anonymous fifteenth-century armour expert observed: ‘if you ask me of what pieces they are made, I reply to you that there is no need for me to declare it more particularly, because all the world knows it, and it is so much in use that it would only make me lose words and time.’ As for the visual artefacts—drawings, diagrams, and extant pieces of arms and armour—these materials, in Anglo’s words, ‘convey most to whose who already know most’. In spite of the inherent limitations of the source material, Anglo has written a remarkable book which illuminates its subject from nearly every imaginable angle. Anglo considers, for example, the tenuous social position of the masters at arms—men who were at once revered for their important skills, but also viewed as a ‘moral and social threat’, as individuals whose area of expertise was not a million miles away from the world of street brawls. He surveys the legal views across Europe regarding deaths that occurred in the course of training in the martial arts. Other topics covered include: the efforts of some writers on the martial arts to en-noble their discipline by linking it to the liberal art of geometry; the disjunction between literary representations of arms and armour and the reality thereof; and the strict social hierarchy of weapons (swords occupied the top position, while staff weapons were considered ‘not really suitable for a gentleman’). Considerable space is devoted to the strategies by which writers of combat manuals sought to illustrate their writings—and to the problems inherent in such an undertaking: ‘a single picture may, at best, suggest that some movement has already started and would continue in another picture, were the artist to execute it. Moreover, such potential movement can usually be completed only in the mind of a viewer already familiar with the story depicted.’ Both the breadth and the depth of the scholarship are dazzling: as befits the topic at hand, Anglo’s work is both multi-disciplinary and panEuropean. It is also an extremely entertaining book. What might, in other hands, have turned into a rather dry, overly technical discussion of the martial arts is in fact brought wonderfully to life by Anglo. All sorts of fascinating characters populate the pages of this book, including King Duarte I of Portugal whose mini-treatise on jousting (embedded within his much larger treatise of horsemanship, The book of instruction for good riding, circa 1434) is credited by Anglo with anticipating the major tenets of twentieth-century sports psychology. The Elizabethan Sir Humphrey Gilbert, best known for his interest in New World exploration, emerges in this context as the driving force behind a failed scheme for an academy for young gentlemen ‘in which arms, letters and public utility might have flourished to their mutual benefit’. This is a book that ought to be read by Renaissance scholars across the disciplines: it adds much to our collective knowledge of the period, while also casting the familiar in a new light. Would that all ‘experimental essays’ were thus. Elizabeth Goldring University of Warwick