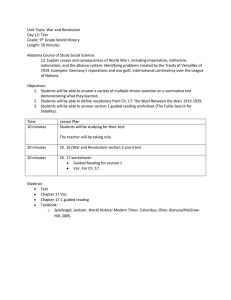

The erosion of the VOC. The VOC and its search... (1740-1796) Chris Nierstrasz (University of Warwick)

advertisement

The erosion of the VOC. The VOC and its search for alternatives to decline (1740-1796)1 Chris Nierstrasz (University of Warwick) Introduction As some European countries are witnessing at this exact moment, getting into debt is not a problem, but getting out of debt is. As it becomes clear that a country might not repay its debts and needs to refinance debts, interest start to soar, and the mountain to climb becomes very steep. Although less dramatic and at a lower level, the VOC struggled with similar problems in the eighteenth century. It was incurring debt in Europe as profitability on trade went down and it was in constant search of ways to finance its trade. This paper is, however, not so much on why the VOC declined, but how it tried to deal with the erosion of its trade. What where the problems the VOC faced in trade? How did it change its ways in financing trade with Asia? Did the vision of how trade needed to be organized changed under pressure from this erosion? As the VOC moved away from monopoly, how did its servants and subjects reacted to these changes? The erosion of the VOC If we look at the main goal of the VOC, trade from Asia to Europe, over nearly two centuries, the VOC greatly increased its trade to Europe. Over the whole period the trade of the VOC was increasing, both in the value of goods brought to Europe as in their value of sales. The total purchase price of the Asian goods rose from 250 million in the seventeenth century to 600 million in the eighteenth century.2 It would be a mistake to simply see the VOC as only invested in the Spice trades as its trade grew more complex over time. Spices proved relatively inelastic in their demand in Europe, which made the search for alternative goods inevitable for growth. Expansion was mostly achieved by accessing new markets of commodities such as cloth, silk, 1 This paper is based on the autor’s Phd-dissertation (2008) entitled: In the Shadow of the Company: The VOC, its servants and its Decline (1740-1796). For a more into depth story on everything discussed in this paper, I refer to this document. 2 Els Jacobs, Merchant in Asia: the Trade of the Dutch East India Company during the Eighteenth Century (Leiden: CNWS Publications, 2006), 6. tea and coffee.3 Over time, the appearance of the VOC changed accordingly as it evolved from simply obtaining profitability from spices. It moved into textiles halfway through the seventeenth century. In the first part of the eighteenth century, it shifting to coffee, tea and new desirables. Often these goods came from areas outside of the regions where the VOC had established itself for its monopoly on spices and according to some authors these goods were responsible for relatively lower gross profit margins of the VOC in the eighteenth century.4 The expansion of investment in different trades was not accompanied by a commensurate expansion in profits of trade. As the VOC succeeded in bring more trade to Europe the relative profitability of its trade went down. When we look at the amounts per guilder earned on the sales in relation to every guilder invested, we see a decline. A paradox existed as the VOC expanded its trade, and succeeded in augmenting its absolute profit from trade, in relative terms the profitability sank to worrisome proportions. The fact that the relative profits declined in the eighteenth century, was strongly accentuated by the ever increasing costs. Even though the VOC is seen as much more docile in the eighteenth century than in the seventeenth, in actual fact costs of enforcing trade and its power rose to unprecedented levels.5 If we take into account these costs, the maintenance of profitability looks much less impressive. The VOC had no choice but to increase trade in order to combat the lesser profitability. The only other possible solution to keep up profitability in Europe was to play a difficult game of imposing rising costs on its Asian branch. In general trading conditions in the eighteenth century, were hampered by increasing competition for trade form European rivals. In opposition to the seventeenth century, the VOC was involved in strong competition with several other European companies for the market in Europe. This was partly the result of its reorientation to goods in which it did not hold a monopoly position. In these markets, if the VOC did not succeed in growing it would lose market share too its competitors In Europe, or differently put: it lost out in competition. This is both exemplified by the English East-India Company, who dramatically increased its share of trade, even taking over the lead of the VOC.6 Several other companies, such as the French, Swedish, Danish and Oostende Company, expanded their trade through specialization in certain products.7 As competition grew fiercer and more competitors stepped into the arena, the VOC increasingly lost control over trade to Europe. In Asia, this competition was felt strongly too. As 3 Femme Gaastra, The Dutch East India Company: Expansion and Decline (Zutphen: Walburg Press, 2003), 129-38. Gaastra, Dutch East India Company, 37-52. 5 George Winius and Marcus Vink, The Merchant-Warrior Pacified: the VOC (the Dutch East India Company) and its Changing Political Economy in India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1991). 6 Holden Furber, Rival Empires of Trade in the Orient, 1600-1800 (London: Oxford University Press, 1976), 89-145. 7 Furber, Rival Empires, 211-29. 4 more Europeans competed for goods, they not only cut into the VOC’s profits in Europe, but also in its profits in intra-Asian trade. All in all, the VOC struggled but managed to keep quite good record in trade and only received a severe blow to its aspirations in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch wars. As the VOC was a sitting duck for its politically much stronger competitor the EIC, it incurred losses during this war from which it never fully recovered. The scope of this paper is the period before, when slowly the problems that would push the VOC to the end in 1796, came to fruition.8 Silver and bills of exchange In order to achieve the necessary growth, the VOC had to invest increasing amounts of capital, which it did not have in Europe. The starting capital of the VOC had been spent on establishing trade in the seventeenth century. So in the Eighteenth century, other sources were responsible for financing the trade of the VOC. The VOC had three tools at its disposal, both with weaknesses and strengths, to capitalize its increasing European trade, namely profits from intra-Asian trade, the export of silver and the acceptance of bills of exchange on Europe. The export of silver is the odd one out, as in opposition to the other two, the VOC tried to limit the investment from silver as much as possible. After the VOC established itself in Asia up to 1630, it succeeded in limiting its exports of silver by resorting to the use of profits from its intra-Asian trade. The VOC skillfully organized its intra-Asian trade as a monopoly tailored to cover the financial demands of its European trade.9 It provided direct profit as Asia was not an integrated market with ample opportunities of profit for trade. This profit was directly used to finance the trade with Europe. At the same time, the intra-Asian trade provided the means for the VOC to obtain goods for Europe at a better price as it had more to offer to Asian merchants in return. Often silver was not very wanted in Asia as it did not serve useful purposes other commodities did. As the VOC obtained goods in Asia, this increased the negotiation position of the VOC in trade too. Direct or indirect profits from intraAsian trade are completely or partially responsible for the cuts in the exports of silver from 1630 until 1680. The monopoly on intra-Asian trade for all subjects of the VOC focused all possible profit from Asia on the European trade. Asian products were obtained at a better price,10 but the system required constant attention and capital was not very flexible towards changing trade patterns. At the same time, the profitability of the system strongly depended on 8 Ingrid Dillo, De nadagen van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, 1783-1795: schepen en zeevarenden (Amsterdam: De Bataafsche Leeuw, 1992). 9 Jonathan Israel, The Dutch Republic: its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1800 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 9413 and Jacobs, Merchant in Asia, 1-4. 10 Gaastra, The Dutch East India Company, 121-3; Jacobs, Merchant in Asia, 1-12. the political control of the Spice Islands.11 The success of the system is clearly distinguishable as for a period of 50 years, the VOC increased its trade simply by ploughing profits from the intraAsian trade into the European trade. As such, the VOC simply received back more from Asia in goods in purchase value than the value of silver it had sent to pay for these cargos. Femme Gaastra has shown that the VOC system of using profits from the intra-Asian trade to finance trade to Europe, structurally changed after 1680.12 The VOC was no longer capable of increasing profits from the intra-Asian trade to keep up with its expanding trade to Europe and with increasing costs in Asia, at least not sufficiently to further off-set silver exports from Europe. After 1680, there was a sharp increase in exports of silver which only ended after 1730, when exports of silver fell and stabilized. Between 1680 and 1730, the export of more silver brought new problems for the VOC.13 Exporting more silver simply meant borrowing more silver on short-term loans, but its limits soon became clear. As the ships returned the following year, the VOC paid off its loans with interest. There was, however, one problem, namely that the VOC was unable to pay off all its short-term loan, signifying that the profits on trade were not enough to off-sett the total costs of the trade. This meant that short-term loans slowly transformed into long-term debts, which to some extent was not a problem as the VOC had plenty of assets on its balance. Debts in the Republic of Seven Provinces rose until in 1736 the Gentlemen XVII, the Directors of the VOC, decided to step in and limit the loans. It was feared that the debt and the interest would otherwise spin out of control and that the VOC would be toppled by its payment of the rents on its loans.14 When it proved difficult to export more silver from Europe, the VOC turned to a different way of financing trade, namely through accepting more money on bills of exchange in Asia. In 1747, the Gentlemen Seventeen decided to double the amount accepted for Europe to 2 million guilders, slowly climbing to 3 million in 1771. This meant that a total of 237 million guilders was accepted in the eighteenth century. This is a very sharp contrast with the 11 Israel, The Dutch Republic, 941-43 and Jacobs, Merchant in Asia, 1-4. Femme Gaastra, ‘De Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw: de groei van een bedrijf. Geld tegen goederen. Een structurele verandering in het Nederlands-Aziatisch handelsverkeer’, in Bijdragen en mededelingen betreffende de geschiedenis der Nederlanden 91 (1976), 249-72 and Femme Gaastra, Bewind en beleid bij de VOC: de financiële en commerciële politiek van de bewindhebbers, 1672-1702 (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 1989) and Gaastra, The Dutch East India Company, 132. 12 13 J . R Bruijn, F. S. Gaastra and I. Schöffer, Dutch-Asiatic Shipping in the 17th and 18th Centuries (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1979-1987) and Om Prakash, ‘Precious-metal Flows in India, Early Modern Period’, in Dennis Flynn, Arturo Giraldez and Richard von Glahn (eds.), Global Connections and Monetary History, 1470-1800 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003). 14 J. P. de Korte, De jaarlijkse financiële verantwoording in de VOC, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (Leiden: Nijhoff, 1984) and Femme Gaastra, The Dutch East India Company: Expansion and Decline (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2003). seventeenth century when only 30 million had been accepted.15 In the literature this is often linked to the increasing acceptance of English money to increase Dutch trade. The timing of the increase (1741) and the moment English really made inroads into the Dutch bills of exchange does not seemed to fit. Increases in English demands and granting of English bills of exchange mainly occurred after 1771 and even more after 1780.16 Yet the increase in acceptance of bills exchange already started in the 1740s. More interestingly, with the changes made in its system of capitalisation, the VOC also reorganised its trade to maximise its capitalisation in Asia. This change of course (1740), altered the VOC stand on private trade and its behaviour towards its servants fundamentally and as such needs to be seen as the starting point of its erosion as a monopoly company. These changes are the subject of the next part of this paper. Monopoly and private trade in Asia Alongside this ever increasing trade together with the development from intra-Asian trade and silver to bills of exchange, a more fundamental difference was the VOC’s shift from absolute monopoly to private trade, both in Asia and in the end to Europe. The VOC felt the pressure of the necessity to increase its trade to keep up profitability, while at the same time it was not in a position to increase its exports of silver from Europe. Already in 1680 it was concluded that the VOC could no longer invest enough money in the intra-Asian trade to make enough profit to pay for its export to Europe. As the VOC was under pressure to export more to Europe, the directors simply decided to keep intra-Asian trade going and to send over more silver, but this proved a limited solution. At the same time, the plans of redress in Holland have received considerable attention as a way to explain the problems the VOC was facing before and after 1780, but it seems that no answer was found in the Republic.17 As no answer was found in Europe, the VOC turned to Asia for a solution. It implemented a change of policy in Asia away from monopoly, which can be traced in the VOC archives both in Jakarta and in The Hague. This part of this paper will be on the changes which arise from these sources. 15 Femme Gaastra, ‘Particuliere geldstromen binnen het VOC-bedrijf 1640-1795’. Van Gelderlezing 2002, 16-26 and Femme Gaastra, ‘Private Money for Company Trade: The Role of Bills of Exchange in Financing the Return Cargoes of the VOC’, in Itinerario 13/1 (1994), 65-76. 16 Gaastra, ‘Private Money for Company Trade’, 65-76 and Femme Gaastra, ‘De VOC en EIC in Bengalen aan de vooravond van de vierde Engelse oorlog (1780–84)’, in Tijdschrift voor zeegeschiedenis, 20 (2001), 24-35. Famous cases are those of VOC Director Ross in Bengal, who helped send English money to the Republic prior to 1780. 17 Jacob Steur, Herstel of ondergang: de voorstellen tot redres van de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, 17401795 (Utrecht: Hes, 1984). In 1740, Governor-General Van Imhoff was sent back to Asia to reorganise the trade of the VOC. He brought with him radical ideas on how to transform trade in Asia to suit the needs of Europe. He felt the VOC was too widely invested in its intra-Asian trade, watering down profitability. A better system would be to limit the investment to the most valuable goods, leaving the rest of the trade to VOC subjects.18 In turn, this free trade could be taxed and would increase the bills of exchange on Europe. From that moment onwards private trade was no longer a taboo in VOC policy. Plans were made how to best institute it with positive effects for the VOC19 and new institutions were created to support private traders.20 The system was regulated from Batavia and changes were made over time to hand over the less profitable trades to private trade or bring profitable new trades back under monopoly. The VOC shrewdly assessed which of its trade were most profitable and kept those under monopoly. The little statistical information we have, seems to point to a decrease in the money the VOC invested in Intra-Asian trade.21 From them an image emerges of a VOC struggling to serve its own needs by allowing private trade. After Van Imhoff, Mossel decided that Van Imhoff had been too liberal and started to issue stricter regulations on the long-distance trading routes to inhibit private trade. He did so without completely banning private trade. His main goal was to make private trade suit the needs of the VOC again. Mossel thought the VOC had been too liberal in allowing private trade in absolute freedom. Not only did the VOC have problems in enforcing its monopoly claims, but with total freedom of trade, servants become too focussed on their own interest instead of the Company’s interests. This had led to a situation, where young servants were able to earn more money than their seniors. This was considered undesirable as it clouded social relations and the VOC hierarchy. In order to restore order, Mossel did two things. He linked private trade privileges to the VOC hierarchy and he stamped down on the exhibition of wealth by instituting 18 J. E. Heeres, ‘De consideratien van Van Imhoff’, in Bijdragen tot de taal- , land- en volkenkunde van NederlandsIndië, 66/1 (1912), 441-621. See also: Nationaal Archief (NA), Hoge Regering van Batavia (HR), 307, Extract Generale Resolutien, 20 September 1743. ‘Taken in the Castle of Batavia in the Council of the Indies, Tuesday the 24 September 1743. With the opening of free shipping and trade to and from this capital to eastern and western India following the qualification of the Gentlemen Seventeen and the licence for that purpose which has already been granted to several citizens, with the exception of the trade in spices, copper, tin and pepper, and in the import of opium, which the Honourable Company shall reserve for itself, as has been decided according to the proposal of the Governor-General.’ 19 NA, Collectie Alting, Consideratien, vrije vaart in Souratta, f38. Report on private trade in Surattata by Jan Schreuder. 20 N. P. van den Berg, De Bataviasche Bank-Courant en Bank van leening 1746-1794 (Amsterdam: Van Kampen, 1870), 4-7. 21 Jacobs, Merchant in Asia, 373, table 47. a rudimentary form of sumptuary law.22 By linking remuneration and exhibition of wealth to hierarchy, it was believed the servants would attach new importance to serving the VOC. Van der Parra, on taking over from Mossel, simply continued to make this system work. First he was as prudent as Mossel in allowing or disallowing private trade. In 1771, however, he made an almost 180 degrees turn on his policy as he suddenly opened up trade between the Indian subcontinent and Batavia completely.23 Factors outside of the VOC power are the only possible explanation for this reversal. The conquest of Bengal by the EIC, made any control of trade between Batavia and Bengal an illusion. As the English seized control of Bengal the rules of the game changed. If the VOC was to exclude English private traders from access to Batavia, it risked to be cut off from access to Bengal itself in retaliation. English private traders increasingly showed up at the road-stead of Batavia and demanded goods. As the VOC no longer had control over trade with the new English interference, Van der Parra no longer saw any reason to exclude VOC subjects from this trade. The use of military force by the English, even brought down what was still left of the VOC’s claims to monopoly in the intra-Asian trade. The English in a next step used their political power to enforce a total breach in the VOC monopoly. When Peace was signed after the Fourth AngloDutch War (1780-1784), the English stipulated free access to all Dutch ports in Asia, even to the Spice Islands. As it was pointless to allow English private traders but not allow such rights to its own subjects, slowly the VOC came to terms with the fact that it should completely leave behind any idea of controlling the intra-Asian trade for its own needs.24 Even stronger, as the position of the VOC further deteriorated, further exploitation of the monopoly between Asia and Europe was searched by the VOC. As long as goods were shipped on VOC ships, VOC subjects were allowed to ship private trade on homeward bound VOC ships when refraining from monopoly goods and on payment of a fee.25 It seems that within the boundaries of regulations, reforms in private trade and the subsequent pressure by the English gave room for Dutch non-state actors in trade, or should this development be differently judged? 22 Van der Chijs, Nederlandsch-Indisch plakaatboek, vol. VI-VII. NA, Hoge Regering, 310, Extract uijt de Generaale Resolutien, 173-7, 27 May 1774. ‘The success of the stipulations made, constant and accurate supervision that our concession is not misused to conduct illicit trade, we have judged it not inexpedient to prescribe some general rules, and these are, first of all, to prevail upon and encourage all prosperous servants and all other subjects of the Company, including the Moorish merchants in Bengal and in Suratta who have some relations with the Company, to fit out ships or other vessels for over there, or to other places where they will be admitted, secondly, to assist them with the necessary precautions.’ 24 ANRI, Hoge Regering 4516, July 1783, Plan Radermacher, 1-13 and ANRI, Hoge Regering 4396, 21 March 1785, Considerations from Ambon, fo. 1-3. 25 Dillo, De nadagen van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, 191-5. 23 The reality of private trade As the profit base from trade to Europe was slowly eroding, the VOC searched for alternatives in Asia to ward off decline. If the VOC liberated intra-Asian trade for its subject, this leaves us with the question to what extent VOC subject became involved in private trade. If we believe the English literature on the subject, private traders should be considered non-state actors, who through freedom of trade changed the commercial dynamics of Asia.26 Maybe the case of the VOC can provided us with new insights and what better way than to look at an eyewitness account of a VOC servant active in private trade.27 From the private correspondence of Lubbert Jan van Eck, it is possible to get an inside view of Dutch private trade during the reign of Governor-General Mossel. In this period trade between the Coromandel Coast and Batavia was regulated for servants, but Dutch free-traders were allowed the right to send over ships to the Coromandel Coast. Apart from trade to Batavia, trade with other regions was left open for servants too. If we would stick to these general regulations, we might be led to believe that freedom of trade existed, but the private trade of Van Eck gives us a much more grim picture of this new world of Dutch private trade. As trade depended on those servants present on the Coast, these servants supplied the goods to the ships. They made sure to call the shots to whom they sold. Even stronger, the private trade system in which Van Eck functioned was strongly based on the VOC hierarchy. Van Eck always made clear that private trade was the prerogative of the higher servants on the spot and that free traders had to accept it.28 In the trade to Batavia, this was even clearer as Mossel had given 26 Holden Furber, Rival Empires of Trade, 272-288; Holden Furber, John Company at Work: a Study of European Expansion in India in the Later Eighteenth Century (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1948) and Ian B. Watson, Foundation for Empire: English Private Trade in India 1659-1760 (New Delhi: Vikas, 1980). 27 NA, archief van Lubbert Jan, Baron van Eck (1719–1765). The private letters which will be studied were written and received by Lubbert Jan van Eck (1719–65) between roughly 1756 and 1765. In approximately 1,500 letters, he corresponded with the other servants in Asia, from the powerful and famous to many other long-forgotten people. After spending a couple of years working in Batavia, he made his career on the Coromandel Coast of India. Ultimately, he became VOC Governor there and later held the same position in the island of Ceylon. He is best remembered as the military commander who won the last major military victory of the VOC. In 1765, he headed the military campaign against the king of Kandy and conquered the Kandyan capital. This victory restored VOC power in the island after a rebellion against VOC authority. Less well known is the fact that he was a successful private trader who amassed an impressive fortune. 28 NA, Coll. Van Eck 20, doc. no 152, 8 August 1758, Van Eck to Faure. ‘Want voor eerst weet Uwed immers weld at voor al op de kleene comptoiren bijna niemand is die negotiert als d’opperhoofden en secundes en dat bij het arrivement van een schip bijna nooyt soo veel gewilde goederen te bekoome zijn als zij selfs van doen hebben om te versenden, of aan de scheepsvrinde met een ordentelijk advans voor contanten of ruyling te verkoope, soo dat Uwed seer ligt kan opmaake dat soo wanneer ik of een ander die goederen heeft late laar make niet van intentie those high in the VOC hierarchy special privileges on VOC ships. Free-traders could never compete with these special privileges as they had to pay for their own ships. Private trade also strongly depended on what the VOC trading structure had to offer. For instance, sugar and arack from Batavia, were the main items brought to the Coast for private trade. These goods were still sold by the VOC, but the servants had ample of room to sell them too.29 The main buyers of these goods were the English and French armies active on the Coromandel Coast. In this manner, the VOC servants indirectly profited from the European military expansion in India. In the return cargos, at this time strongly restricted for VOC servants to VOC ships, cloth was brought back. In Batavia, it was either bought by the ships officers for their private allowance for Europe or by Chinese merchants trading to Manila.30 As this was a strongly related to the hierarchy only the highest placed officials had access to cargo space through privileges. Such privileges were also extended to the members of the High Government in Batavia.31 Without these privileges and without the help of VOC sevants on the Coast, it was very hard to have a profitable stake in this trade or to compete with the servants. On the Coast itself, Europeans relied on each other and on indigenous traders to obtain and sell what they needed. Even here the VOC stipulated that private trade had to be conducted with the official VOC suppliers in order to keep trade within the group. Still, in order to obtain the desired goods, often Van Eck worked with other Europeans. At first with the French, but the moment they became politically untenable, he decided to cut them off. Oddly, he continued contact with his French partners in order to facilitate trade between the French and English partners. Indigenous merchants were also employed as super cargos on Van Eck’s zijn, om deselve voor een bagatel van de handt te zetten en soo men Uwed deselve in rekening bragt soo als men deselve verkoopt en Uwed deselve in rekening bragt soo als men deselve verkoopt en Uwed dan 20 per cent daar boove betaalde soo zoude Uwed naa gedagte niet veel daar meede profiteere voor al zoo men op zijn Batavias te werk ging met nogh 5 per cent aan comissie en soo veel aan tol en andere kleenigheede in rekening te brenge buyte en behalve dat zoekt Uwed door het aangaan van diergelijke projecten met de scheepsvrienden die Uwed ook 60 per cent op haar aanbreng belooft heeft en anders het broot uyt de mont te sooten en kan Uwed immers wel naagaan Uwed geen mensen zal vinden die zigh met sulke commisie zoude wille ophoude en die het wel zoude willen doen sal het wel belet werde soo dat Uwed al seen goet vriendt raade van dat project afte zien het welke een jeder zeer vreemt en om Uwed de waarheyt te zeggen al te inhaalig is voorgekoome en tn eerste als een loopent fuurtje langs de Cust heeft gegaan.’ 29 NA, Hoge Regering 27, doc. no 1, exact date unknown. Even though the sugar trade has been left in the hands of the private traders, the Company still fills the empty cargo space to the Western Quarters with sugar. 30 NA, Coll. Van Eck 20, doc. no 477, 3 June 1760, Van Eck to Faure & Cordua. Scheepsvrienden were the officers of the East Indiamen. 31 Van der Chijs, Nederlandsch-Indisch Plakaatboek, VII, 755, 13/16 April 1764. ‘The exception to this rule is the little the gentlemen of this government need for their household use. In the cloth settlements, it will be necessary for those given the commission to hand the packages in at the Company warehouse, so that they are sent over with the Company goods and to list them on the Company bill of lading.’ And P. Groot, Accompaniments to Letters from Negapatam (Madras: Government Press 1911), 184. private trade ships. So there existed enough trust to work with them. Whole crews consisted of indigenous sailors too. Another interesting story is his relationship with the Armenian merchants from Madras. He worked with them on a direct expedition to Manilla, which also involved the VOC governor of Malacca. At the same time, the VOC servants did impose their will on indigenous merchant in positions of competition.32 The same was true for European competition to Batavia.33 Even the Dutch free burghers in Batavia were kept away from private trade, in order for high officials to profit from their position.34 Private trade should not be considered the only or most lucrative way to own a fortune for servants.35 When we analyse the data from Van Eck’s correspondence, a clear distinction is needed between his period on the Coromandel Coast and in Ceylon. Servants preferred working in areas where the VOC held colonies to regions where they only held private trade privileges. In the regions where the VOC allowed private trade, the Company had allowed servants to profit from its intra-Asian profits before. The fact that now servants had to invest their own money, run risk and have less profit was not judged as enough by the VOC servants.36 At the same time, VOC servants sought to maximize privileges and if possible even stray away from the rules.37 If we look at the regions where VOC servants held private trade privileges, it seems they were not exactly happy with their position. Having a position in a region with colonies, simply gave more power and thus more access to fortune. Conclusion 32 NA, Coll. Van Eck 18, doc. no 9, 17 November 1757, Van der Parra to Van Eck. ‘It is essential not to accede to the request of the Armenians of Madras, and if feasible also to achieve an interdiction on the sending of cloths by the Moors and merchants from the Malabar. This is to clear the way for those, who would otherwise be prevented from making an acceptable profit, and who would find themselves in [financial] difficulties because of these heathens.’ ‘ Om dus den wegh te baenen voor die gene, die andersints het behaelen van een gepermitteert winstje zoude werde belet, en door dese heijdenen moeijelijk gemaakt.’ 33 Van der Chijs, Nederlandsch-Indisch plakaatboek, 1761 Van der Parra, 514, 14 August. Regulation, that the foreign ships in the roadstead of Batavia should be accorded the least possible help. 34 NA, Hoge Regering, 27, 10 October 1764, §22. Trade was kept for the officials, instead of increasing the wealth of the burgers of Batavia. 35 Nicholas Dirks, The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), 38. ‘If the Company allowed no private trade, their servants must starve.’ 36 NA, Coll. Van Eck 20, doc. no 359, 15 October 1759, Van Eck to Van der Parra. ‘Nowadays a Governor has at his disposal only what he earns by his personal participation in the trade, of which he has to spent a large part to sustain his pomp and circumstance.’ 37 NA, Coll. Van Eck 20, doc. no 259, 5 February 1759, Van Eck to Mossel and NA, Coll. Van Eck 20, doc. no 261, 5 February 1759, Van Eck to Faure & Cordua. Although the VOC succeeded in increasing its trade in the eighteenth century, it mostly financed this increase from its Asian part. As it did not have the means to expand its exports of silver endlessly, the only way forward was to find capitalization in Asia. This begs the question how they were able to increase income in Asia, certainly as the intra-Asian trade profits were not endless either. Even stronger, the VOC should not be seen as the great monopolist in intraAsian trade as it embarked on changes in this policy in order to maximize European trade. This paper only provides part of the answer as it explores how the VOC put part of the burden of financing trade on its servants. As bills of exchange grew more important, the question is how servants found their fortunes to buy these bills. If we listen to the servants, they preferred other ways of remuneration over private trade as it was considered unfair to invest their own money, run the risk of trade and end up with less money than before. At the same time, Dutch private trade was not detached from the VOC and its hierarchy; it was only in acknowledging this fact that both the servants and free-burghers had room to maneuver. All in all, in this strange situation where a company was behaving as a proto-state it is hard to see VOC servant as non-state actors.