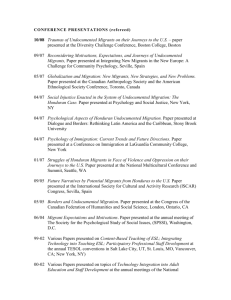

M Some Thoughts on Perceptions and Policies Mexico-United States Labor Migration Flows:

advertisement