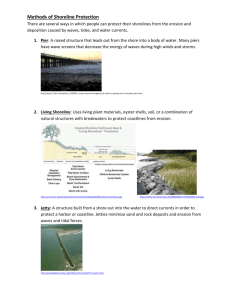

SHORE EROSION CONTROL GUIDELINES for Waterfront Property Owners

advertisement