Ceremony 2 25 November 2008 Education for Sustainable Development

advertisement

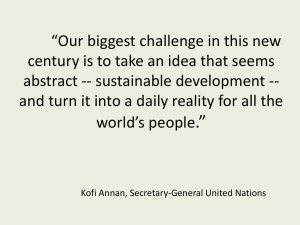

Ceremony 2 25 November 2008 Education for Sustainable Development Dr Paul Pace Director, Centre for Environmental Education & Research Honourable Minister, Chancellor, Rector, colleagues, distinguished guests, parents and graduands: it is indeed a privilege and honour to have been asked to address you on the occasion of this special celebration. This event is a celebration for several reasons. As an educational community, we are celebrating. The results of the many concerted efforts to provide educational programmes integrating various disciplines into a coherent whole. We are also celebrating and renewing our commitment towards ensuring that future generations are provided with opportunities to develop and realise their goals. This is reassuring and encouraging for all, parents in particular but society in general. Much is expected of you considering the investment made to support your education. Last but not least, we are celebrating with all graduands: your personal sacrifice, diligence, study and commitment which ensured the successful completion of your studies to earn the award that you will be receiving shortly. Although having reached this important milestone in your lives is good reason to celebrate, it is opportune to recall the cost of your endeavour. It hasn’t been easy. You are well aware of the challenges you had to face; the feelings of frustration, helplessness and anticipation you had to deal with; and the many times you had to go against the grain to complete your work or prepare for your examinations. But you wouldn’t be here today if you hadn’t worked hard in the past. All good things come at a cost and success is no exception. Besides being the culmination of your efforts, this graduation ceremony is effectively your recognition as active participants in the wider community and society which initially recognised your potential and provided you with resources to fulfil this potential. We all owe a lot to a society and community which believes in our skills and should gratefully accept to pay back in kind. Unfortunately, this happy occasion is not one which can be universally shared. You may know others who started a programme but had to stop. It is also appropriate to reflect upon and think about others who may only dream of being here or worst still cannot even comprehend such a dream: there are some, 115 million children around the world (the vast majority being girls) who will not have the opportunity to get a primary education, let alone a university degree; girls and children from poorer or rural families are least likely to attend school; and one child in five who have made it into the system and is old enough to attend secondary school is still enrolled in primary school. We are truly part of the lucky few who rightfully expect access to education as part of our entitlement. But besides finding time to appreciate this fundamental human right that we have received freely as a result of the struggles that previous generations went through, we need to recognise our responsibility to ensure that this process continues and extends through the work of our professions thus ensuring a good quality of life for all. Faced with this reality we can just sit here and feel sorry or, even worse, say that it doesn’t concern us because we cannot do anything about it. On the other hand we might realise that in this globalised world of interrelations and interconnections every localised pull at the strands of this complex web of interactions will be felt and have its repercussion on the wider arena. Becoming aware of the situation around us is but the first step in becoming functional world citizens. Translating knowledge into understanding and ultimately into action is the function of education for sustainable development. Literature abounds with definitions of sustainable development: ranging from the overarching description coined in the Bruntland Report1 (defining it as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs) to more schematic representations showing the interaction of ecological, social and economic concerns. Sustainable development is essentially a commitment to ensure socially responsible economic development while protecting the resource base and the environment for the benefit of future generations2. However, even a cursory analysis at the progress made since targets for sustainable development were set by the Rio de Janeiro World Summit (1992) shows that sustainable development has only been given lip service and its slow implementation has been attributed to a general lack of political will to take bold and radical decisions towards its implementation3. Many analysts have suggested that the implementation of sustainable development necessitates a deeper change that goes beyond the introduction and application of new technologies. This deeper change necessitates an ethical backdrop to our actions and implies the adoption of personal lifestyles that are characterised by the values of “simplicity, moderation and discipline, as well as a spirit of sacrifice” that are the antidotes for the “collective selfishness, disregard for others and dishonesty” that are the root of the crises that we are currently facing4. The UN’s concern with promoting an educational process that supports the sustainable development process by developing a global value system has been consistent since the first Conference on Human Environment held in Stockholm (1972). Throughout its major conferences, the UN endeavoured to bring to the forefront the central role that education has in sustainable development. The culmination of these efforts was the launch of the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD) spanning from January 2005 – December 20145 based on eight Key Action Themes: Gender Equality; Health Promotion; Environment; Rural Development; Cultural Diversity; Peace & Human Security; Sustainable Urbanization; and Sustainable Consumption. Albert Einstein reportedly said that “today’s problems cannot be resolved using the same thinking that created them” and, as reiterated during the 10th Conference of Environmental Education in Europe (2008, Valletta), ESD is essentially a challenge for the individual and society to think and act outside the box because: switching on to sustainable living requires courage to depart from our comfort zones (i.e., lifestyles/habits that we’ve become accustomed to) and determination to continue pushing forward with practices that will only yield fruit in the future. relating ecological, social and economic concerns in decision making requires the ability to think differently and conceive alternative ways of conducting the economy game and measuring progress. we are paying dearly for the sins of yesterday … i.e. the aftermath of past policies (or lack of them) that have managed our resources carelessly or by crises. This has particular relevance to a small island with the highest population density in Europe. Relying solely on technical solutions has proved to be ineffective and still we tend to persist in this approach. I feel that we need to approach sustainable development issues with a wider perspective … trying to find solutions in places that we never thought could offer us a way out. we need to view the role of civil society differently. There is great scope in developing a community that is conscious of its impact on the surroundings and is ready to take an active role in the resolutions of sustainable development issues. This implies perceiving civil society as a colleague and a partner in decision making rather than consider it as a client or a threat. keeping civil society ignorant of the reasons why certain actions are needed and presenting ready-made policies tend to generate inactivity in the populace, focus attention on short term results and erode accountability and shared responsibility. Sustainable development cannot thrive in a context where citizens feel more comfortable with having someone to decide, think and provide for them. Locally, ESD is already generating change, particularly at the formal education sector. Various programmes have been proposed at various educational levels, but continuity between each level is still noticeably lacking. We need to develop a clear national policy about ESD that is reflected within the National Curriculum. Such a policy will also need to address the informal and non-formal sectors to promote lifelong community-based ESD programmes, targeting adult learners in particular and providing meaningful learning experiences which nurture and foster sustainable lifestyles. Sadly, we are one of the few EU countries lacking such a policy. ESD is not a passing fad. Experiences from around the world are showing that it is proving to be an essential component in the educational baggage of every citizen especially for policy makers, managers/administrators and professionals. ESD will surely feature in your future. Whilst congratulating you once again for your achievement, I invite you to honour your profession and the investment put into you by your dear ones and society by putting sustainable development concerns as a top priority in your personal and professional agenda. Thank you. 1 2 3 4 5 WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development) (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. UNCED (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development) (1992). The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development: A Guide to Agenda 21. Switzerland: UN Publications Office, Geneva. United Nations (2002) Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development. Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August - 4 September 2002. New York: United Nations. John Paul II (1989) Peace with God the Creator, Peace with all of Creation. Message for the celebration of the World Day of Peace. 1 January 1990. Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. UNESCO (2005) Report by the Director-General on the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: International Implementation Scheme and UNESCO’S Contribution to the Implementation of the Decade. Paris: UNESCO