THE COHEN INTERVIEWS ROSE MARY BRAITHWAITE

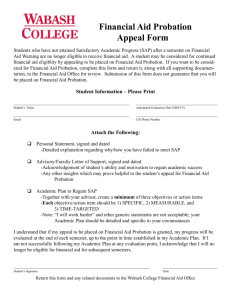

advertisement