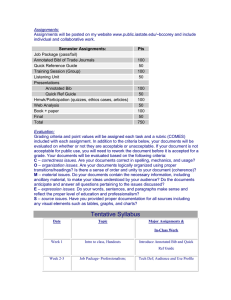

Omeros

advertisement