Negative regulation of the RTBV promoter by designed zinc finger proteins

advertisement

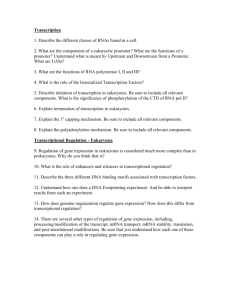

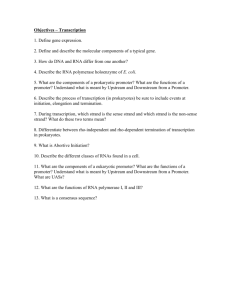

Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 DOI 10.1007/s11103-010-9600-0 Negative regulation of the RTBV promoter by designed zinc finger proteins M. Isabel Ordiz • Laurent Magnenat • Carlos F. Barbas III • Roger N. Beachy Received: 2 September 2009 / Accepted: 8 January 2010 / Published online: 19 February 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract The symptoms of rice tungro disease are caused by infection by a DNA-containing virus, rice tungro bacilliform virus (RTBV). To reduce expression of the RTBV promoter, and to ultimately reduce virus replication, we tested three synthetic zinc finger protein transcription factors (ZF-TFs), each comprised of six finger domains, designed to bind to sequences between -58 and ?50 of the promoter. Two of these ZF-TFs reduced expression from the promoter in transient assays and in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants. One of the ZF-TFs had significant effects on plant regeneration, apparently as a consequence of binding to multiple sites in the A. thaliana genome. Expression from the RTBV promoter was reduced by *45% in transient assays and was reduced by up to 80% in transgenic plants. Co-expression of two different ZF-TFs did not further reduce expression of the promoter. These experiments suggest that ZF-TFs may be used to reduce replication of RTBV and thereby offer a potential method for control of an important crop disease. Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11103-010-9600-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. M. I. Ordiz R. N. Beachy (&) Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, 975 N. Warson Road, St. Louis, MO 63132, USA e-mail: Rnbeachy@danforthcenter.org L. Magnenat C. F. Barbas III The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and the Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, BCC-550, North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA Present Address: L. Magnenat Merck Serono S.A., 9 Chemin des Mines, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Keywords Gene regulation Repression RTBV promoter Transcription factors Synthetic zinc fingers Introduction Rice tungro disease (RTD) is caused by co-infection by rice tungro bacilliform virus (RTBV) and rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV). RTBV is the primary causal agent of disease symptoms while RTSV provides functions that permit transmission of the disease agents by the green leafhopper. RTBV is a pararetrovirus and its genome of double stranded DNA is replicated primarily in phloem and phloem associated tissues. The genome of RTBV has been well characterized as has its transcriptional promoter (Yin and Beachy 1995; Yin et al. 1997a) and the transcription factors that bind to and activate its expression. The ‘E’ fragment of the promoter (nucleotides -164 to ?45) is sufficient to confer high-level, tissue-specific gene expression. Previous studies of the promoter characterized the cis elements that confer phloem-specific expression and several transcription factors that are important for expression. The cis elements include a GATA motif [nucleotides (nt) -143 to -135], AS1-like (ASL) Box (nt -98 to -79), Box II (nt -53 to -39), and Box I (nt -3 to ?8) (He et al. 2000, 2001, 2002; Yin and Beachy 1995; Yin et al. 1997a). Box II plays an essential role in expression of genes driven by the RTBV promoter and two host transcription factors that bind to the Box II cis element have been identified and partially characterized: RF2a (Dai et al. 2003; Yin et al. 1997b) and RF2b (Dai et al. 2004). RF2a and RF2b bind to and activate transcription from the RTBV promoter (Dai et al. 2003, 2004, 2006; Petruccelli et al. 2001; Yin et al. 1997b). A goal of our research is to reduce replication of 123 622 RTBV, and therefore mitigate disease symptoms, by reducing RTBV gene expression. The Cys2His2 class of zinc finger proteins (ZFPs) is the most abundant family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana; of 176 known ZFPs, 33% are conserved amongst other eukaryotes and 81% are plant specific (Englbrecht et al. 2004). These proteins have a wide range of functions and can bind to other proteins and to RNA and DNA. Cys2His2 proteins have a bba fold that most typically recognizes three contiguous base pairs (bp) of DNA sequence. This property has been used to design synthetic zinc finger protein transcription factors (ZF-TFs) that can regulate gene expression in a variety of different organisms (reviewed in Blancafort et al. 2004). Several recent reports have shown that synthetic ZF-TFs can be used to regulate gene expression in plants. In earlier studies we used a well-characterized six-finger ZF-TF, 2C7 (Liu et al. 1997), and its cognate DNA binding site in transient assays in plant protoplasts and transgenic plants (Ordiz et al. 2002; Stege et al. 2002) to alter gene expression. Expression of a reporter gene was enhanced by a 2C7 activator protein in BY-2 protoplasts; furthermore, the distance between the TATA box and the 2C7 binding site affected the efficiency of ZF-TF regulation of gene expression (Ordiz et al. 2002; Stege et al. 2002). We also showed that a ZF-TF activator could be applied to cause tissue specific expression of a target gene in transgenic tobacco plants (Ordiz et al. 2002). Stege et al. (2002) explored the use of both activation and repression domains with the 2C7 ZF-TF protein, reporting that the SID domain of the human MAD protein linked to a ZF-TF repressed gene expression by fivefold. Guan et al. (2002) designed ZF-TFs to regulate the promoter of the Apetala3 (Ap3) gene in A. thaliana and used the AP1 promoter to drive expression of AP3-ZFP-TF and demonstrated control of expression of the endogenous gene. Other groups have used ZF-TFs to regulate plant metabolism (Holmes-Davis et al. 2005; Sanchez et al. 2006; Van Eenennaam et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2004). Others have used chemically inducible promoters to control expression of ZF-TFs (Beerli et al. 2000a, b; Sanchez et al. 2002). New applications of sZFP nucleases to cleave, repair, induce mutations, and effect homologous recombination in plants and other organisms, including Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, Xenopus, and mammalians cells, have recently been described (Cai et al. 2009; Kandavelou and Chandrasegaran 2009; Lloyd et al. 2005; Shukla et al. 2009; Wright et al. 2005; reviewed by Durai et al. 2005; Porteus and Carroll 2005; Wu et al. 2007). The goal of the current study was to identify ZF-TFs that reduce expression of the RTBV promoter. We designed three ZF-TFs to bind to sequences proximal to the TATA box of the RTBV promoter. Data from transient assays in tobacco BY-2 protoplasts and transgenic Arabidopsis 123 Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 plants indicated that two ZF-TFs down-regulate the RTBV promoter, causing a 40–80% decrease in the expression of the genes driven by the promoter, while the third protein had a negative effect on plant development. Materials and methods Sequences of RTBV promoters analyzed EMBL accession numbers of the RTBV sequences compared in this study were AF113830 (G1), AF113831 (G2), AF113832 (Ic), X57924 (Phi-1), M65026 (Phi-2), D10774 (Phi-3, Cabauatan et al. 1999), AF076470 (Serdang, Marmey et al. 1999), AF220561 (Chainat isolate, Nathwong et al. 2000, unpublished), AJ314596 (West Bengal, Nath et al. 2002), NC_001914 (Hay et al. 1991). Assembly of zinc finger proteins and specificity of protein binding Open reading frames encoding ZF-TFs were generated by PCR using domain sequences and methods described previously (Dreier et al. 2001, 2005; Segal et al. 1999). ZF-TF2 was designed to bind nucleotides 50 AAGAG AGCAAGAGAGGAG30 with the following zinc finger DNA recognition helices (amino acids -1 to ?6 are shown in brackets): F1-GAG (RSDNLVR), F2-GAG (RSDNLVR), F3-AGA (QLAHLRA), F4-GCA (QSGDLRR), F5-AGA (QLAHLRA), and F6-AAG (RKDNLKN). ZF-TF3 was designed to bind 50 AGGGGCACACTGGTCATT30 with recognition helices as follows: F1-ATT (HKNALQN), F2-GTC (DPGALVR), F3-CTG (RNDALTE), F4-ACA (SPADLTR), F5-GGC (DPGHLVR), and F6-AGG (RSDHLAE). ZF-TF8 was designed to bind 50 GGAG TCCAGGGGCACACT30 with recognition helices F1-ACT (THIDLIR), F2-CAC (NLQHLGE), F3-GGG (RSDKLVR), F4-CAG (RADNLTE), F5-GTC (DPGALVR), and F6-GGA (QSSHLVR). Assembled DNAs encoding three-finger proteins that bind half-sites were subcloned by SfiI digestion and cloning into a modified pMal-C2 bacterial expression vector (NEB, MA) (Beerli et al. 1998), and joined as pairs using restriction endonucleases for the construction of six-finger proteins. Proteins were tested with multi-target specificity ELISA as described (Magnenat et al. 2004; Segal et al. 1999). ZF-TF proteins fused to maltose binding protein and hemaglutinin tags were overexpressed in E. coli. Crude extracts of each ZF-TF were obtained by freeze–thaw cycles. Twofold serial dilutions of the extracts were tested individually for comparing their binding to different immobilized biotinylated hairpin oligonucleotides (MWG-biotech) containing the appropriate 18-bp target sequences. Bound protein was Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 detected with a mouse anti-maltose binding protein mAb conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and substrate addition (SIGMA, MO). Absorbance at 405 nm (OD405) was quantitated with SOFTmax 2.3.5 (Molecular Devices, CA), background subtracted, normalized to a maximum binding signal of 100% for each ZF-TF, and presented as the average of duplicate experiments with standard deviations. Proteins were tested in electrophoretic mobility shift assays as described (Liu et al. 1997). The probes were generated using double stranded oligonucleotides containing the recognition sites of the ZF-TF (described above) labeled with c-[32P] ATP. The radioactive signal was taken using a Typhoon PhosphoImager (Molecular Dynamics, CA) and the data were analyzed using ImageQuant Software 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics, CA). Plasmids for transfection assays The plasmid RTBV-FL:GUS (Yin and Beachy 1995) contains the full length RTBV promoter comprised of the nucleotides (nt) -731 to ?45, RTBV-E:GUS (Yin and Beachy 1995) contains RTBV promoter nt -164 to ?45 and RTBV-E*:GUS nt -164 to ?58; each was ligated with the uidA open reading frame. The effector constructs were expressed under the control of a constitutive cassava vein mosaic virus (CsVMV) promoter (Verdaguer et al. 1998) from plasmids designated ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, ZF-TF8, ZFTF2S, ZF-TF3S, and ZF-TF8S; the latter three constructs contain the SID transcription repression domain of the human MAD protein fused to the N-terminus of the ZF-TF protein. To develop the effector genes ZF-TF2S, ZF-TF3S, and ZF-TF8S, the open reading frames were released from vectors pcDNA-SIDZF-TF2, pcDNA-SIDZF-TF3, and pcDNA-SIDZF-TF8 using the restriction enzymes NheI and HindIII. ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, and ZF-TF8 were obtained from pcDNA-ZF-TF2VP64, pcDNA-ZF-TF3VP64, and pcDNA-ZF-TF8VP64; the VP64 domain was removed using AscI and PacI. The vector was reassembled using HindIII and ApaI in order to clone the coding sequence into a plasmid containing the CsVMV promoter. An SV40 large T nuclear localization signal (NLS) was inserted in the ZF-TFs between SID and the ZF-TF protein and in the ZF-TFs at the C-terminal of the protein. 623 Gene constructs ZF-TF2-8 and ZF-TF2S-8S were created adding the ZF-TF8 and ZF-TF8S removed from their respective plasmids with NotI and placed into the HindII site in the polylinker of the binary vector already containing the ZF-TF2 and ZF-TF2S constructs. Transient expression assays Protoplasts isolated from suspension cultures of tobacco BY-2 cells (N. tabacum L., cv. Bright Yellow-2) were transfected via electroporation as described by Watanabe et al. (1987). The protoplasts were co-transfected with a mixture of DNAs, including 10 lg of reporter gene construct, 20 lg of effector DNA, 5 lg of internal control plasmid containing the chimeric gene p35S:GFP, and 10 lg of herring sperm DNA using a discharge of 125 lF and 300 V through disposable 0.4 cm cuvettes. Each transient assay was repeated three times per experiment and each experiment was conducted three times. Plant transformation Plasmids containing the effector constructs were transferred by electroporation into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101. Agrobacterium isolates that contained the respective plasmids were used to transform a homozygous line of A. thaliana Col-0 that contained the reporter gene RTBV-E:GUS by the standard floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). T1 seeds were germinated in Murashige and Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) containing glufosinateammonium (10 mg/l) and carbenicillin (250 mg/l) and seedlings that survived the selection were grown in soil in a growth chamber, allowed to self-fertilize, and T2 seeds were collected. T2 seeds were germinated in selective medium and seedlings that survived selection and exhibited a segregation ratio of 3: 1 for glufosinate resistance were grown in soil in the growth chamber (200 lmol m-2 s-1 12 h light/12 h dark, 22°C, 50% HR), allowed to self-fertilize, and T3 seeds were collected. T3 seeds were germinated in Murashige and Skoog medium containing glufosinateammonium and homozygous seedlings were grown in soil in the growth chamber (200 lmol m-2 s-1 12 h light/12 h dark, 22°C, 50% HR), allowed to self-fertilize, and T4 seeds were collected. Gene constructs for plant transformation Fluorescence GUS assays Gene constructs ZF-TF2, ZF-TF8, ZF-TF2S, and ZF-TF8S were removed from their respective plasmids with NotI and placed into the BamHI site in the polylinker of the vector pGJ366. The vector pGJ366 is a modification of the plasmid pPZP200 (Hajdukiewicz et al. 1994) and provides resistance of transgenic plants to glufosinate-ammonium (BASTA). GUS extraction buffer was added to homogenized leaf samples from the transgenic plants and the mixture was centrifuged. The supernatants were used to determine enzymatic activity by the method of Jefferson et al. (1987). Enzyme activity was determined by quantifying fluorescence using a spectrofluorometer (Spectramax Gemini, 123 624 Molecular Devices, CA) with 365-nm excitation wavelength and 455-nm emission wavelength. Green fluorescence protein (GFP) activity was determined by quantifying fluorescence using 490 nm excitation wavelength and 530 nm emission wavelength. The concentration of total protein in the extract was measured by the dye-binding method of Bradford (1976). Histological GUS assay Samples of leaf tissue were collected and stained with filter-sterilized 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl b-D-glucuronide (X-Gluc, Glycosynth, UK) staining solution (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.5% DMSO, 20% methanol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM X-Gluc). After vacuum filtration samples were incubated at different periods of time at 37°C. At the appropriate time, the X-Gluc solution was replaced and chlorophyll was removed with 70% ethanol. Tissues were examined with an Olympus SZX12 microscope with bright-field optics. Northern blot assays RNA was purified from leaf tissues using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (50 lg) was separated on a denaturing 1.5% agarose gel made with Northern Max 10x Denaturing Gel Buffer (Ambion, TX). The RNA was then transferred to and cross linked to Hybond N-positive membrane (Amersham, PA). After washing the membrane with prehyb/ hybridization buffer (Ambion, TX), the membrane was incubated with a radioactive DNA probe containing the gene sequence encoding the ZF-TF8 protein and the first 600 bases pairs of the uidA gene. The membrane was hybridized overnight at 42°C and later washed to remove nonspecifically bound radioactivity. Images were taken of the membrane using a Typhoon PhosphoImager (Molecular Dynamics, CA) and the data analyzed using ImageQuant Software 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics, CA). Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 AF113832 (Ic), X57924 (Phi-1), M65026 (Phi-2), D10774 (Phi-3, Cabauatan et al. 1999), AF076470 (Serdang, Marmey et al. 1999), AF220561 (Chainat isolate, Nathwong et al. 2000, unpublished), AJ314596 (West Bengal, Nath et al. 2002), NC_001914 (Hay et al. 1991). Based on evaluation of the consensus sequence of the promoter region, several 18 bp target sites were chosen and three-six finger ZF-TF sequences, referred to as ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, and ZFTF8, were designed (Fig. 1 and supplementary Fig. A1). Site selection was based on the availability of modular zinc finger domains previously selected by phage display to bind triplets represented in GNN, ANN, and CNN with reference to individual sequence specificity and binding characteristics (Dreier et al. 2001, 2005; Segal et al. 1999). When known sequences of Oryza sativa (Yu, 2002) and A. thaliana were searched for potential binding sites for these ZFTFs using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) none was found. The ZF-TFs were designed to bind in regions conserved among different virus isolates and without overlap with binding sites of known plant transcription factors (e.g., GATA, ASL, and TATA box). The binding sites for ZF-TF3 and ZF-TF8 overlap with each other on sequences proximal to the Box II cis element. Previous work revealed that transcription factors RF2a and RF2b bind to Box II (Dai et al. 2004; Yin et al. 1997b) and it was proposed that the virus requires RF2a and RF2b, and perhaps other Results Design of ZF-TFs to bind the RTBV promoter The aim of this study was to reduce expression of genes driven by the promoter of RTBV using artificial zinc finger transcription factors (ZF-TFs). We first compared the sequences of ten different isolates of RTBV from various regions of South and Southeast Asia where the virus is endemic. EMBL accession numbers of the virus sequences compared were AF113830 (G1), AF113831 (G2), 123 Fig. 1 Diagram of the E fragment of the RTBV promoter with the location of the different sequences targeted by the designed zinc finger proteins (ZF-TFs) Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 Transient reporter gene assays in protoplasts A transient assay in tobacco BY-2 protoplasts was used to assess the ability of the ZF-TFs to regulate expression of the genes driven by the RTBV promoter in plant cells. The reporter construct contained the full length RTBV promoter (RTBV-FL, nt 2731 to ?45) ligated with the uidA (GUS) coding sequence to create RTBV-FL:GUS (Yin and Beachy 1995). The ZF-TFs with and without the SID (S) repressor domain (Ayer et al. 1996) fused at the amino terminus were evaluated. The SID domain is known to act as repressor in human cells and in some plant cells (Ayer et al. 1996; Beerli et al. 1998; Stege et al. 2002). The effector genes were placed under the control of the cassava vein mosaic virus (CsVMV) promoter (Verdaguer et al. 1998). These constructs were designated ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, ZF-TF8, ZF-TF2S, ZF-TF3S, and ZF-TF8S (Fig. 3a). The reporter gene was introduced (by electroporation) alone or co-introduced with the effector constructs into BY-2 protoplasts. Three independent experiments were conducted, each with three samples per experiment. GUS activity was measured 24 h after electroporation using a quantitative GUS assay (Jefferson et al. 1987). As shown in (A) 100 ZF-TF protein - -T F3 ZF -T ZF -T ZF (B) Probe F8 zf-2 zf-3 zf-8 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 F2 RELATIVE BINDING (O.D. 405 nm) factors, for replication (Dai et al. 2006). Previous data demonstrated that targeting ZF-TFs bearing repression domains to the 50 UTR of the human ErbB2 and ErbB3 genes efficiently reduced expression of these promoters (Beerli et al. 1998, 2000b). To determine if this was successful in plant cells ZF-TF2 was designed to bind a highly conserved region within the 50 UTR of the primary RTBV transcript (Fig. 1). The expression vectors for the ZF-TFs were built using PCR-based gene assembly with oligonucleotides containing the desired sequences. Three-finger proteins targeting 9-bp half-sites were first constructed by PCR overlap extension and then assembled as pairs to produce proteins that contain 6-finger domains. These ORFS were then cloned into the pMAL expression vector and the ZF-TFs were expressed in E. coli. The fusion proteins were tested using multi-target DNA binding ELISA as described (Segal et al. 1999). The binding specificity of each of the pMALZF-TF2, pMAL-ZF-TF3, and pMAL-ZF-TF8 fused to the maltose binding protein was measured individually for biotinylated hairpin-loop DNA oligonucleotides containing the three different target sequences (Fig. 2a). Also, electrophoretic mobility shift assays were carried out using the fusion proteins containing the ZF-TFs against the different binding recognition sequences used as probes (Fig. 2b). Even though zf-3 and zf-8 target sequences share 11 nucleotides, there was no cross-reaction with the heterologous ZF-TFs in these assays. Each ZF-TF shows excellent specificity for its target sequence (Fig. 2). 625 zf-2 zf-3 zf-8 2 3 8 - 2 3 8 - 2 3 8 Fig. 2 Specific binding of the recognition sequences with the ZF-TF. a Multi-target DNA specificity ELISA of the different ZF-TFs. The six-zinc finger proteins ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3 and ZF-TF8 were tested individually for binding to each other DNA target site zf-2 (black bars), zf-3 (grey bars) and zf-8 (white bars) in duplicate experiments. The maximum binding signal for each protein was normalized to 100%. b Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using different ZF-TFs. The duplex DNA oligonucleotides containing the difference recognition sequence zf-2, zf-3 and zf-8 were labeled with c [32P]ATP and used as a probe. 50 lg of different ZF-TFs were used into gel shift reactions with the probes containing the three different target sequences Fig. 3b and considering RTBV-FL:GUS as 100% of GUS activity: protoplasts that also contained ZF-TF2 exhibited 60% GUS activity; ZF-TF2S, 57%; ZF-TF3S, 70%; ZFTF8, 67% and ZF-TF8S, 49%. In contrast ZF-TF3 did not reduce expression of the reporter gene. ZF-TF2 and ZFTF8 reduced GUS activity between 35 and 40%. Constructs that contained the SID domain did not reduce GUS production to a greater extent than ZF-TF2, while in the case of ZF-TF3 reduction was minor, and in ZF-TF8 was about 15%. We conducted similar experiments using the RTBV-E* promoter (nt -164 to ?58 (data not shown). Compared with the amount of enzyme activity produced by RTBVE*:GUS (set at 100%), ZF-TF2 permitted 42% of GUS activity; ZF-TF2S permitted 35%; ZF-TF3 permitted 80%; ZF-TF3S permitted 72%; ZF-TF8 permitted 76% and ZFTF8S permitted 48%. In the case of the RTBV-E promoter (nt -164/?45) (data not shown), and considering activity produced by the construct RTBV-E:GUS as 100%, ZF-TF2 produced 50% of GUS activity; ZF-TF2S permitted 39%; ZF-TF8 permitted 63% and ZF-TF8S permitted 43%. The degree of reduction of gene expression was similar in the RTBV-FL and the RTBV-E* promoter. 123 626 Fig. 3 Analysis of the effect of ZF-TFs on expression of the RTBV promoter in tobacco BY-2 protoplasts. a Diagram of the RTBV full length promoter (comprising nt -731 to ?45), E (nt -164 to ?45) and E* (nt -164 to ?58) fused to the uidA gene and the plasmids containing the CsVMV promoter driving the genes encoding ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, ZF-TF8, or ZF-TFs fused to the SID repressor domain, i.e., ZF-TF2S, ZF-TF3S and ZF-TF8S. b Expression of GUS activity in BY-2 protoplasts transfected with the RTBV full length promoter and plasmids containing the CsVMV promoter driving the genes encoding ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, ZF-TF8, ZF-TF2S, ZF-TF3S and ZF-TF8S. Quantification of GUS activity from extracts 24 h after transfection. Protoplasts were co-transfected with a mixture of 10 lg of the reporter gene, 20 lg of plasmids encoding ZF-TFs, 5 lg of the 35SGFP plasmid and 10 lg of herring sperm DNA. Results are expressed as amount of GUS activity compared with GFP activity and expressed as a percentage of activity produced by the RTBV-FL:GUS plasmid. The results are the average of three independent transfection reactions ±SD Activity of the ZF-TFs in transgenic Arabidopsis plants To evaluate the activity of the ZF-TFs in Arabidopsis, ZFTFs or ZF-TFSs were introduced into the vector pGJ366 and used to develop transgenic plants using BASTA as the selectable agent. Constructs containing individual effectors, i.e., ZF-TF2, ZF-TF8, ZF-TF2S and ZF-TF8S, a combination of two effectors (ZF-TF2-8 plus ZF-TF2S-8S) were introduced into a line that contained the reporter gene RTBV-E:GUS. The RTBV-E fragment comprises nt -164 to ?45 (Fig. 4a). Plants resistant to BASTA were grown in a growth chamber and analyzed via PCR for the presence 123 Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 Fig. 4 Effect of ZF-TFs on expression of RTBV-E:GUS in T1 transgenic Arabidopsis plants. a Diagram of the plasmids used to transform a transgenic plant line that contains the RTBV-E (nt -164 to ?45):GUS reporter construct. The effector constructs contain the CsVMV promoter fused to genes encoding single ZF-TFs; i.e., ZFTF2, ZF-TF8, ZF-TF2S or ZF-TF8S or two ZF-TFs, i.e., ZF-TF2-8 or ZF-TF2S-8S. b GUS activity in leaves of 15 T1 Arabidopsis plants (6 weeks old). The activity of the transgenic plant line RTBV-E:GUS was normalized to 100% of the reporter and effector genes. At least 15 transgenic T1 plants containing one of each of the different ZF-TFs were analyzed at 6 weeks after planting. The GUS activity in extracts of leaves from the line containing the reporter gene only was defined as 100%. T1 plant lines that also contained ZF-TF2 exhibited an average decrease of 60% in GUS activity. Plant lines that contained ZF-TF8 showed an average decrease in GUS activity of 80%, whereas plant lines with ZF-TF2 plus ZF-TF8 (ZFTF2-8) showed an average decrease of 60%. ZF-TF2S caused a slight increase in repression when compared with ZF-TF2, although the SID domain did not increase the repression by ZF-TF8 (Fig. 4b). The results of these studies demonstrate that a suitable ZF-TF can cause a significant reduction in GUS activity and that the SID domain does not enhance the effect significantly. The T1 plants were allowed to self-fertilize and T2 seeds of plants containing ZF-TF8 and ZF-TF8S were studied. We did not recover fertile plants from lines that produced ZF-TF2. Fifteen seedlings from six different lines with segregation ratios of 3:1 were grown for 6 weeks and GUS activity was determined in leaf extracts. The repression of GUS activity in these lines ranged from 20 to 60% (data not shown). Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 T2 plants were allowed to self-fertilize and T3 seeds were collected; homozygous seeds that produced seedlings under selective conditions were analyzed. Sixteen seedlings each from six different homozygous lines were grown in soil for 6 weeks, leaf extracts were obtained, and GUS activity was determined. The GUS activity in the homozygous lines containing ZF-TF8 was reduced 50–80% compared with the activity in extracts of the parent plant line that contained only the reporter gene. GUS activity in the line containing ZF-TF8 plus the SID domain (ZFTF8S) was reduced 20–30% (Fig. 5a). These studies confirmed that ZF-TF8 was capable of significantly reducing expression of genes driven by the RTBV promoter. 627 (Fig. 4a). In these analyses a decrease in GUS activity was correlated with reduced levels of cognate mRNA. Samples analyzed from tissue that contained ZF-TF8S had levels of uidA mRNA similar to the controls. Similarly, the levels of GUS activity were only slightly reduced in plants that expressed ZF-TF8S relative to plant lines that expressed only the reporter gene. Plant lines with high levels of ZFTF8 mRNA had low levels of uidA mRNA and GUS activity. Furthermore, there was a strong positive correlation between GUS activity (Fig. 5a) and the levels of uidA mRNA (Fig. 5b), and low levels of GUS activity were correlated with high levels of ZF-TF8 mRNA (Fig. 5b). Histochemical analysis of GUS activity Correlation of GUS activity with mRNA levels RNA was isolated from leaves from the parent line and from several lines that contain RTBV-E:GUS and ZF-TF8 or ZF-TF8S. Non-transgenic Col-0 was used as a negative control in these studies. Total RNA (50 lg) was separated in a denaturing gel and transferred to a nylon membrane. The levels of expression of the ZF-TFs were determined using a probe containing sequences from uidA and ZF-TF8 Tissues from six plants from homozygous lines containing the reporter gene alone or with ZF-TF8 were collected and GUS activity was detected by staining with 5-bromo-4chloro-3-indolyl b-D-glucuronide (X-Gluc). All samples were stained for identical periods of time to avoid saturation of the reaction. Non-transgenic Col-0 plants were used as negative control. We did not observe staining in any of the tissues of the non-transgenic plants. In plants containing the GUS reporter gene alone or with ZF-TF8, stain was observed primarily in the vascular system as reported in tobacco and rice (Petruccelli et al. 2001; Yin et al. 1997b). However, the intensity of staining was greater in plants containing only the reporter plasmid than in plants that produced the ZF-TF (Fig. 6). From this data we concluded that the presence of ZF-TF8 under the control of a constitutive promoter altered the amount of GUS in cells in vascular tissues. These observations are in agreement with the quantitative assays reported above. Discussion Fig. 5 Effect of ZF-TF8 alone or with the SID repressor domain on GUS expression, activity and mRNA levels, in homozygous Arabidopsis transgenic lines. a GUS activity in leaves of T3 homozygous Arabidopsis plants (6 weeks old) containing the RTBV-E:GUS plasmid and the CsVMV promoter fused to genes encoding the ZFTF8 alone or fused with the SID repressor, ZF-TF8S. b Northern blot to determine the presence of uidA and ZF-TF8 mRNA. Leaf extracts from the same plants were used to obtain total RNA. 50 lg of total RNA were loaded in each lane from young leaves taken from multiple plants from each line. The probe used was made from the first 600 bp from the amino terminal end of the uidA gene and the full gene of ZFTF8. The GUS activity of the transgenic plant line RTBV-E:GUS was normalized to 100% The goal of this study was to determine the effectiveness of artificial zinc finger transcription factors (ZF-TFs) to reduce expression of genes driven by the RTBV promoter in transgenic plants and plant cells. ZF-TFs have been previously used in strategies to control replication and/or infection by viruses, including the DNA virus herpes simplex virus and the retrovirus HIV (Eberhardy et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2005; Papworth et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2003; Segal et al. 2004), in mammalian cells. Sera (2005) described a ZF-TF that restricts the replication of the single-stranded-DNA-containing Geminivirus beet curly top virus by binding to the origin of replication. Three target regions in the RTBV promoter were selected based on the consensus sequences of 10 isolates of RTBV, and three-six-finger transcription factors, ZF-TF2, ZF-TF3, and ZF-TF8, were designed to bind to these 123 628 Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 Fig. 6 Histochemical localization of GUS in wild type Col-0 and transgenic Arabidopsis plants containing RTBV-E:GUS alone or plus the ZF-TF8 driven by the constitutive CsVMV promoter. In leaf tissue, cross section of stem tissue, whole roots, flowers and siliques. GUS activity was localized following staining of tissue slices with X-Gluc and visualizing the indigo dye precipitates formed via light microscopy sequences. ZF-TFs offer high specificity in sequence recognition and are anticipated to regulate expression of target genes with minimal side effects. A search of genomic sequences of A. thaliana and O. sativa did not reveal identical matches with the predicted binding sites of the designed ZF-TFs. However, there were two potential binding sites in the genome A. thaliana for ZF-TF2 that each contained a single mismatch. Interestingly, we did not recover viable T2 seeds from transgenic plants that produced ZF-TF2, a result that suggests that this protein, but not ZF-TF3 or ZF-TF8, interfered with fertility, perhaps by binding to DNA sequences that are important in these processes. These results indicate the importance of careful design and testing of ZF-TFs. 123 Binding sites for each of the ZF-TFs tested in this study are proximal to the TATA Box of the promoter (Fig. 1). The proximity of the target sequence to the TATA box was critical to the efficacy of ZF-TFs in regulation of gene expression in plants in other studies (Guan et al. 2002; Ordiz et al. 2002; Stege et al. 2002). ZF-TF3 and ZF-TF8 binding sites are proximal to the Box II cis element of the RTBV promoter, a region known to bind to transcription factors RF2a and RF2b; these factors activate expression of the promoter (Dai et al. 2004; Yin et al. 1997b). ZF-TF2 binds in the 50 UTR region of the genome-length transcript. The efficacy of the ZF-TFs was first tested in BY-2 protoplasts in an attempt to predict their activity in whole plants. ZF-TF2 reduced GUS activity by 40% compared to Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 controls, and addition of the SID domain (ZF-TF2S) did not increase repression. ZF-TF3 did not repress GUS activity except in constructs that contained the SID domain (ZF-TF3S). ZF-TF8 repressed GUS activity by 35% and addition of the SID domain (ZF-TF8S) increased repression to 50%. These data agree with previous studies that indicated that the SID domain provides a modest enhancement of repression of gene expression by ZF-TFs in plant cells (Stege et al. 2002). In T1 Arabidopsis plants that expressed ZF-TF2 and ZFTF8, GUS gene expression was reduced between 60 and 80%, i.e., greater than the effects observed in transient assays. These results may indicate that repression is more complete when the target gene is integrated into the host genome vs as free DNA. In homozygous populations, repression of the reporter gene ranged from 20 to 30% among different transgenic lines that expressed ZF-TF8S and between 50 and 80% among lines that contained ZFTF8. This data indicates a strong negative regulatory effect of expression of uidA gene driven by the RTBV promoter by the ZF-TF8 protein in the absence of the SID domain. The data presented here support previous results that location of the binding site of the ZF-TFs within the Box II element provides efficient repression (Dai et al. 2006). The fact that ZF-TF2 binds downstream of this element and was effective may reflect some regulatory activity within this area (He et al. 2000, 2002) or may imply that the area is easily accessible to binding by the protein. In support of the hypothesis that other regulatory proteins may bind in this area and may compete with binding of the relevant ZF-TF, we note that the repression of activity of ZF-TFs used in this study was not significantly increased through fusion with the SID repression domain. This result is in contrast to the results reported by Beerli et al. (1998) and Guan et al. (2002), where addition of the SID domain to ZF-TFs substantially improved repression. Since the SID domain is not an exceptionally potent repressor in plants, the activity of ZF-TFs might be further improved by addition of a different repression domain. Based on these studies, we conclude that the RTBV promoter can be negatively regulated using six-finger ZF-TFs. The possibility that these or other ZF-TFs can reduce replication of RTBV in transgenic rice plants remains to be demonstrated, and presents a potential application of ZF-TFs to control of an important plant disease. Acknowledgments We thank Dr. Jitender Yadav for his assistance with the RNA work and Dr. Shunhong Dai for providing some materials and for helpful discussions during the early stages of this work. This study was supported by Department of Energy grant DOEFG02-99ER20355, and NASA grant NNJ04HG98G to RNB and by a grant from The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology to CFB. 629 References Ayer DE, Laherty CD, Lawrence QA, Armstrong AP, Eisenman RN (1996) Mad proteins contain a dominant transcription repression domain. Mol Cell Biol 16:5772–5781 Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Dreier B, Barbas CF III (1998) Toward controlling gene expression at will: specific regulation of the erbB-2/HER-2 promoter by using polydactyl zinc finger proteins constructed from modular building blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:14628–14633 Beerli RR, Schopfer U, Dreier B, Barbas CF 3rd (2000a) Chemically regulated zinc finger transcription factors. J Biol Chem 275:32617–32627 Beerli RR, Dreier B, Barbas CF 3rd (2000b) Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes by designed transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:1495–1500 Blancafort P, Segal DJ, Barbas CF 3rd (2004) Designing transcription factor architectures for drug discovery. Mol Pharmacol 66:1361– 1371 Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254 Cai CQ, Doyon Y, Ainley WM, Miller JC, Dekelver RC, Moehle EA, Rock JM, Lee YL, Garrison R, Schulenberg L, Blue R, Worden A, Baker L, Faraji F, Zhang L, Holmes MC, Rebar EJ, Collingwood TN, Rubin-Wilson B, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Petolino JF (2009) Targeted transgene integration in plant cells using designed zinc finger nucleases. Plant Mol Biol 69:699–709 Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16:735–743 Dai S, Petruccelli S, Ordiz MI, Zhang Z, Chen S, Beachy RN (2003) Functional analysis of RF2a, a rice transcription factor. J Biol Chem 38:36396–36402 Dai S, Zhang Z, Chen S, Beachy RN (2004) RF2b, a rice bZIP transcription activator, interacts with RF2a and is involved in symptom development of rice tungro disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:687–692 Dai S, Zhang Z, Bick J, Beachy RN (2006) Essential role of the Box II cis element and cognate host factors in regulating the promoter of Rice tungro bacilliform virus. J Gen Virol 87:715–722 Dreier B, Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Flippin JD, Barbas CF 3rd (2001) Development of zinc finger domains for recognition of the 50 -ANN-30 family of DNA sequences and their use in the construction of artificial transcription factors. J Biol Chem 276:29466–29478 Dreier B, Fuller RP, Segal DJ, Lund CV, Blancafort P, Huber A, Koksch B, Barbas CF 3rd (2005) Development of zinc finger domains for recognition of the 50 -CNN-30 family DNA sequences and their use in the construction of artificial transcription factors. J Biol Chem 280:35588–35597 Durai S, Mani M, Kandavelou K, Wu J, Porteus MH, Chandrasegaran S (2005) Zinc finger nucleases: custom-designed molecular scissors for genome engineering of plant and mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 33:5978–5990 Eberhardy SR, Goncalves J, Coelho S, Segal DJ, Berkhout B, Barbas CF 3rd (2006) Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication with artificial transcription factors targeting the highly conserved primer-binding site. J Virol 80:2873–2883 Englbrecht CC, Schoof H, Bohm S (2004) Conservation, diversification and expansion of C2H2 zinc finger proteins in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. BMC Genomics 5:39–56 Guan X, Stege J, Kim M, Dahmani Z, Fan N, Heifetz P, Barbas CF 3rd, Briggs SP (2002) Heritable endogenous gene regulation in 123 630 plants with designed polydactyl zinc finger transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13296–13301 Hajdukiewicz P, Svab Z, Maliga P (1994) The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol 25:989–994 Hay JM, Jones MC, Blakebrough ML, Dasgupta I, Davies JW, Hull R (1991) An analysis of the sequence of an infectious clone of rice tungro bacilliform virus, a plant pararetrovirus. Nucleic Acids Res 19:2615–2621 He X, Hohn T, Futterer J (2000) Transcriptional activation of the rice tungro bacilliform virus gene is critically dependent on an activator element located immediately upstream of the TATA box. J Biol Chem 275:11799–11808 He X, Futterer J, Hohn T (2001) Sequence-specific and methylationdependent and -independent binding of rice nuclear proteins to a rice tungro bacilliform virus vascular bundle expression element. J Biol Chem 276:2644–2651 He X, Futterer J, Hohn T (2002) Contribution of downstream promoter elements to transcriptional regulation of the rice tungro bacilliform virus promoter. Nucleic Acids Res 30:497–506 Holmes-Davis R, Li G, Jamieson AC, Rebar EJ, Liu Q, Kong Y, Case CC, Gregory PD (2005) Gene regulation in planta by plantderived engineered zinc finger protein transcription factors. Plant Mol Biol 57:411–423 Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW (1987) GUS fusions bglucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J 6:3901–3907 Kandavelou K, Chandrasegaran S (2009) Custom-designed molecular scissors for site-specific manipulation of the plant and Mammalian genomes. Methods Mol Biol 544:617–636 Kim YS, Kim JM, Jung DL, Kang JE, Lee S, Kim JS, Seol W, Shin HC, Kwon HS, Van Lint C, Hernandez N, Hur MW (2005) Artificial zinc finger fusions targeting Sp1-binding sites and the trans-activator-responsive element potently repress transcription and replication of HIV-1. J Biol Chem 280: 21545–21552 Liu Q, Segal DJ, Ghiara JB, Barbas CF 3rd (1997) Design of polydactyl zinc-finger proteins for unique addressing within complex genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:5525–5530 Lloyd A, Plaisier CL, Carroll D, Drews GN (2005) Targeted mutagenesis using zinc-finger nucleases in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2232–2237 Magnenat L, Blancafort P, Barbas CF 3rd (2004) In vivo selection of combinatorial libraries and designed affinity maturation of polydactyl zinc finger transcription factors for ICAM-1 provides new insights into gene regulation. J Mol Biol 341:635–649 Marmey P, Bothner B, Jacquot E, de Kochko A, Ong CA, Yot P, Siuzdak G, Beachy RN, Fauquet CM (1999) Rice tungro bacilliform virus open reading frame 3 encodes a single 37kDa coat protein. Virology 253:319–326 Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15:473–497 Nath N, Mathur S, Dasgupta I (2002) Molecular analysis of two complete rice tungro bacilliform virus genomic sequences from India. Arch Virol 147:1173–1187 Ordiz MI, Barbas CF 3rd, Beachy RN (2002) Regulation of transgene expression in plants with polydactyl zinc finger transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:13290–13295 Papworth M, Moore M, Isalan M, Minczuk M, Choo Y, Klug A (2003) Inhibition of herpes simplex virus 1 gene expression by designer zinc-finger transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:1621–1626 Petruccelli S, Dai S, Carcamo R, Yin Y, Chen S, Beachy RN (2001) Transcription factor RF2a alters expression of the rice tungro bacilliform virus promoter in transgenic tobacco plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:7635–7640 123 Plant Mol Biol (2010) 72:621–630 Porteus MH, Carroll D (2005) Gene targeting using zinc finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 23:967–973 Reynolds L, Ullman C, Moore M, Isalan M, West MJ, Clapham P, Klug A, Choo Y (2003) Repression of the HIV-1 50 LTR promoter and inhibition of HIV-1 replication by using engineered zinc-finger transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:1615–1620 Sanchez JP, Ullman C, Moore M, Choo Y, Chua NH (2002) Regulation of gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana by artificial zinc finger chimeras. Plant Cell Physiol 43:1465–1472 Sanchez JP, Ullman C, Moore M, Choo Y, Chua NH (2006) Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana 4-coumarate:coenzyme-A ligase-1 expression by artificial zinc finger chimeras. Plant Biotech J 4:103–114 Segal DJ, Dreier B, Beerli RR, Barbas CF III (1999) Toward controlling gene expression at will: selection and design of zinc finger domains recognizing each of the 50 -GNN-30 DNA target sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:2758–2763 Segal DJ, Goncalves J, Eberhardy S, Swan CH, Torbett BE, Li X, Barbas CF 3rd (2004) Attenuation of HIV-1 replication in primary human cells with a designed zinc finger transcription factor. J Biol Chem 279:14509–14519 Sera T (2005) Inhibition of virus DNA replication by artificial zinc finger proteins. J Virol 79:2614–2619 Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi VM, Rock JM, Wu YY, Katibah GE, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson MA, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt SA, Butler HJ, Hinkley SJ, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD (2009) Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zincfinger nucleases. Nature 459:437–441 Stege JT, Guan X, Ho T, Beachy RN, Barbas CF 3rd (2002) Controlling gene expression in plants using synthetic zinc finger transcription factors. Plant J 32:1077–1086 Van Eenennaam AL, Li G, Venkatramesh M, Levering C, Gong X, Jamieson AC, Rebar EJ, Shewmaker CK, Case CC (2004) Elevation of seed alpha-tocopherol levels using plant-based transcription factors targeted to an endogenous locus. Metab Eng 6:101–108 Verdaguer B, de Kochko A, Fux CI, Beachy RN, Fauquet C (1998) Functional organization of the cassava vein mosaic virus (CsVMV) promoter. Plant Mol Biol 37:1055–1067 Watanabe Y, Mushi T, Okada Y (1987) Infection of tobacco protoplasts with in vitro transcribed tobacco mosaic virus RNA using an improved electroporation method. FEBS Lett 219:65–69 Wright DA, Townsend JA, Winfrey RJ Jr, Irwin PA, Rajagopal J, Lonosky PM, Hall BD, Jondle MD, Voytas DF (2005) Highfrequency homologous recombination in plants mediated by zinc-finger nucleases. Plant J 44:693–705 Wu YM, Mao X, Wang SJ, Li RZ (2004) Improving the nutritional value of plant foods through transgenic approaches. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 20:471–476 Wu J, Kandavelou K, Chandrasegaran S (2007) Custom-designed zinc finger nucleases: what is next? Cell Mol Life Sci 64:2933– 2944 Yin Y, Beachy RN (1995) The regulatory regions of the rice tungro bacilliform virus promoter and interacting nuclear factors in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J 7:969–980 Yin Y, Chen L, Beachy R (1997a) Promoter elements required for phloem-specific gene expression from the RTBV promoter in rice. Plant J 12:1179–1188 Yin Y, Zhu Q, Dai S, Lamb C, Beachy RN (1997b) RF2a, a bZIP transcriptional activator of the phloem-specific rice tungro bacilliform virus promoter, functions in vascular development. EMBO J 16:5247–5259 Yu JI (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. Indica). Science 296:79–92 Supplementary figure A1. DNA sequence alignment and consensus within the promoter region of 10 different virus isolates of Rice Tungro Bacilliform Virus (RTBV). Identical regions are in red, conserved blocks are in orange and regions of low homology are in green. Positions of known plant transcription factors (ASL and TATA boxes, virus ciselements Boxes I and II) (thin arrows) and 18 bp target sites of designed six-zinc finger transcription factors ZF-TF2, -3 and -8 (thick arrows) are represented. 1