Constraints and Opportunities of Horticulture Production and Marketing in Eastern Ethiopia

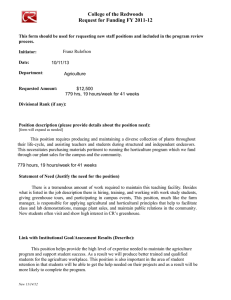

advertisement

Constraints and Opportunities of Horticulture Production and

Marketing in Eastern Ethiopia

By Bezabih Emana and Hadera Gebremedhin

February 2007

DCG Report No. 46

Constraints and Opportunities of Horticulture Production and

Marketing in Eastern Ethiopia

Bezabih Emana and Hadera Gebremedhin

DCG Report No. 46

February 2007

The Drylands Coordination Group (DCG) is an NGO-driven forum for exchange of practical

experiences and knowledge on food security and natural resource management in the drylands of Africa..

DCG facilitates this exchange of experiences between NGOs and research and policy-making

institutions. The DCG activities, which are carried out by DCG members in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Mali and

Sudan, aim to contribute to improved food security of vulnerable households and sustainable natural

resource management in the drylands of Africa.

The founding DCG members consist of ADRA Norway, CARE Norway, Norwegian Church Aid,

Norwegian People's Aid, The Strømme Foundation and The Development Fund. The secretariat of DCG

is located at the Environmental House (Miljøhuset G9) in Oslo and acts as a facilitating and

implementing body for the DCG. The DCG’s activities are funded by NORAD (the Norwegian Agency

for Development Cooperation).

This study was carried out by the CARE Ethiopia for the Drylands Coordination Group.

Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the DCG secretariat.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the

author(s) and cannot be attributed directly to the Drylands Coordination Group.

© Emana, B., and Gebremedhin, H., Drylands Coordination Group Report No. 46 (02, 2007)

Drylands Coordination Group c/o Miljøhuset G9

Grensen 9b

N-0159 Oslo

Norway

Tel.: +47 23 10 94 90

Fax: +47 23 10 94 94

Internet: http://www.drylands-group.org

ISSN: 1503-0601

Photo credits: T.A. Benjaminsen, Gry Synnevåg and Bezabih Emana

Cover design: Spekter Reklamebyrå as, Ås.

Printed at: Mail Boxes ETC.

Table of Contents

ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................................ VII

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................................................VIII

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................................................................IX

1.

INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

2.

BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 1

OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................................. 2

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT .................................................................................................................. 2

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY ........................................................................................................................ 2

METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................. 4

2.1

DATA COLLECTION ...................................................................................................................................... 4

2.1.1

Producers’ survey .................................................................................................................................. 4

2.1.2

Consumers’ survey ................................................................................................................................. 5

2.1.3

Focus group discussion.......................................................................................................................... 6

2.1.4

Secondary data....................................................................................................................................... 6

2.2

DATA ANALYSIS .......................................................................................................................................... 6

3.

SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RESPONDENTS ............................................................................ 7

3.1

PRODUCERS ................................................................................................................................................. 7

3.1.1

Demographic features ............................................................................................................................ 7

3.1.2

Education ............................................................................................................................................... 8

3.1.3

Means of livelihood ................................................................................................................................ 8

3.2

CONSUMERS ................................................................................................................................................ 9

3.2.1

Demographic features ............................................................................................................................ 9

3.2.2

Means of livelihood of the consumers .................................................................................................. 10

4.

HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 12

4.1

4.2

4.2.1

4.2.2

4.3

4.3.1

4.3.2

4.3.3

4.3.4

4.3.5

4.3.6

4.4

4.5

4.5.1

4.5.2

5.

FARMING SYSTEM IN THE AREA ................................................................................................................. 12

TYPES OF HORTICULTURE PRODUCED IN THE AREA .................................................................................. 15

Vegetables ............................................................................................................................................ 15

Fruits.................................................................................................................................................... 15

INPUT USE FOR HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 16

Land allocated for horticulture production.......................................................................................... 16

Irrigation .............................................................................................................................................. 17

Labor.................................................................................................................................................... 19

Fertilizer and manure........................................................................................................................... 19

Seeds/seedlings..................................................................................................................................... 20

Pesticides ............................................................................................................................................. 21

VEGETABLE PRODUCTION, SUPPLY AND INCOME ....................................................................................... 22

PROFITABILITY OF HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 25

Cost of production................................................................................................................................ 25

Production and marketing efficiency ................................................................................................... 26

INPUT SUPPLY SYSTEM.............................................................................................................................. 28

5.1

INSTITUTIONS AND POLICIES...................................................................................................................... 28

5.2

INPUT SUPPLY CHANNEL ........................................................................................................................... 28

5.2.1

Seeds/seedlings..................................................................................................................................... 31

5.2.2

Fertilizer............................................................................................................................................... 32

5.2.3

Pesticides ............................................................................................................................................. 32

5.2.4

Farm equipment ................................................................................................................................... 33

6.

CONSTRAINTS AND PROSPECTS OF HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION ......................................... 35

6.1

6.2

7.

CONSTRAINTS ............................................................................................................................................ 35

OPPORTUNITIES FOR HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION ................................................................................... 36

HORTICULTURE MARKETING IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA ................................................................... 38

7.1

MARKETS FOR HORTICULTURE PRODUCTS ................................................................................................ 38

iii

7.1.1

7.1.2

7.1.3

7.1.4

7.1.5

7.1.6

7.1.7

7.2

7.2.1

7.2.2

7.2.3

7.2.4

7.2.5

7.2.6

7.2.7

7.3

7.3.1

7.3.2

7.3.3

7.3.4

7.3.5

7.4

7.5

8.

Finkile market ...................................................................................................................................... 39

Haramaya market................................................................................................................................. 40

Kombolcha market ............................................................................................................................... 41

Woter market........................................................................................................................................ 42

Harar market........................................................................................................................................ 42

Dire Dawa market................................................................................................................................ 43

Djibouti market .................................................................................................................................... 44

MARKETING CHANNEL AND THE MAJOR ACTORS ..................................................................................... 44

Producers ............................................................................................................................................. 45

Collectors ............................................................................................................................................. 45

Brokers ................................................................................................................................................. 46

Retailers ............................................................................................................................................... 46

Wholesalers .......................................................................................................................................... 46

Exporters .............................................................................................................................................. 47

Consumers............................................................................................................................................ 48

MARKET FACILITIES/INFRASTRUCTURE..................................................................................................... 52

Transportation...................................................................................................................................... 52

Storage ................................................................................................................................................. 54

Grading, standardization and packaging............................................................................................. 54

Financing ............................................................................................................................................. 55

Market information .............................................................................................................................. 56

CONSTRAINTS OF HORTICULTURE MARKETING ......................................................................................... 56

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INCREASED HORTICULTURE MARKETING ................................................................. 58

PRICE ANALYSIS .......................................................................................................................................... 60

8.1

8.2

8.3

9.

PRICES OF HORTICULTURAL PRODUCTS IN THE DOMESTIC MARKET ......................................................... 60

MARKETING MARGINS .............................................................................................................................. 61

DJIBOUTI MARKET..................................................................................................................................... 62

GENDER ASPECT OF HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION AND MARKETING .................................. 64

9.1

9.2

10.

PRODUCTION PARTICIPATION ..................................................................................................................... 64

MARKETING DECISION .............................................................................................................................. 64

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................... 65

10.1

CONCLUSIONS............................................................................................................................................ 65

10.2

RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................................................................. 65

10.2.1

Improving the horticulture production ............................................................................................ 65

10.2.2

Improving marketing of horticultural products............................................................................... 66

11.

REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................................... 68

ANNEXES .................................................................................................................................................................. 69

ANNEX 1: PRODUCERS' QUESTIONNAIRE (PRODUCTION AND MARKETING) ............................................................. 69

ANNEX 2: CONSUMERS' QUESTIONNAIRE (PRODUCTION AND MARKETING) ............................................................ 77

ANNEX 3: LIST OF KEY INFORMANTS AND EXPERTS FROM DIFFERENT INSTITUTIONS .............................................. 81

ANNEX 4: LIST OF KEY INFORMANTS AND FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION PARTICIPANTS FROM DEVELOPMENT

STATION, PEASANT ASSOCIATION & WOREDA LEVEL INSTITUTIONS ....................................................................... 83

iv

List of Tables

TABLE 1: DISTRIBUTION OF SAMPLE HORTICULTURE PRODUCERS INCLUDED IN THE SURVEY ......................................... 5

TABLE 2: NUMBER OF CONSUMERS INCLUDED IN THE SURVEY BY SEX ........................................................................... 6

TABLE 3: AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND DEPENDENCY RATIO .................................................................................... 7

TABLE 4: MARITAL STATUS OF THE HOUSEHOLD HEADS BY WOREDA.............................................................................. 8

TABLE 5: LEVEL OF EDUCATION OF THE HOUSEHOLD HEADS BY WOREDA ....................................................................... 8

TABLE 6: AVERAGE NO. OF CHILDREN IN SCHOOL PER SAMPLE HOUSEHOLD .................................................................. 8

TABLE 7: MAJOR MEANS OF INCOME GENERATION OF THE HORTICULTURE PRODUCERS ................................................. 9

TABLE 8: CONSUMERS' HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND FAMILY LABOR AVAILABILITY .............................................................. 10

TABLE 9: LEVEL OF EDUCATION OF THE HOUSEHOLD HEAD (CONSUMERS)................................................................... 10

TABLE 10: ANNUAL INCOME AND ITS PROPORTION ALLOCATED FOR THE PURCHASE OF HORTICULTURAL PRODUCTS .. 11

TABLE 11: AREA ALLOCATED TO VEGETABLES DURING THE DIFFERENT PRODUCTION CYCLES .................................... 13

TABLE 12: PROPORTION OF HOUSEHOLDS PRODUCING VEGETABLES (2005/06 PRODUCTION YEAR) ............................. 15

TABLE 13: NUMBER OF FRUIT TREES PER HOUSEHOLD .................................................................................................. 16

TABLE 14: AVERAGE CROPLAND HOLDING, IRRIGABLE LAND AND USE INTENSITY (HA) ............................................... 16

TABLE 15: TYPES OF CROPS PRODUCED BY USING IRRIGATION ..................................................................................... 17

TABLE 16: SOURCE OF WATER FOR IRRIGATION ............................................................................................................ 18

TABLE 17: PROPORTION OF HOUSEHOLDS WITH DIFFERENT METHODS OF IRRIGATION.................................................. 18

TABLE 18: SOURCES OF LABOR FOR HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION................................................................................ 19

TABLE 19: LABOR USE FOR SELECTED VEGETABLE CROP PRODUCTION......................................................................... 19

TABLE 20: NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS APPLYING ANIMAL MANURE TO VEGETABLES ................................................... 20

TABLE 21: USE OF CHEMICAL FERTILIZER FOR SELECTED VEGETABLE CROPS............................................................... 20

TABLE 22: SOURCE OF PESTICIDES PURCHASED BY FARMERS ....................................................................................... 21

TABLE 23: PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED IN USING PESTICIDE ........................................................................................... 22

TABLE 24: AREA ALLOCATED TO VEGETABLES AND NUMBER OF PRODUCERS IN DIFFERENT WOREDAS ......................... 22

TABLE 25: PRODUCTION AND UTILIZATION OF VEGETABLES ........................................................................................ 23

TABLE 26: REASONS WHY PRODUCTION/SUPPLY INCREASED DURING THE LAST 5 YEARS ............................................. 24

TABLE 27: COST OF PRODUCTION OF SELECTED VEGETABLES....................................................................................... 26

TABLE 28: PRODUCTION AND MARKETING EFFICIENCY AT PRIMARY AND TERMINAL MARKETS ................................... 27

TABLE 29: SOURCES OF IMPROVED SEEDS OF HORTICULTURAL CROPS IN THE STUDY AREA ......................................... 31

TABLE 30: FARMERS' RESPONSE ON SOURCES OF IMPROVED SEED ................................................................................ 32

TABLE 31: SOURCE OF FERTILIZER FOR HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION .......................................................................... 32

TABLE 32: INSTITUTIONS SUPPLYING PESTICIDES ......................................................................................................... 33

TABLE 33: INSTITUTIONS SUPPLYING SPRAYERS/WATER PUMPS ................................................................................... 34

TABLE 34: TOP THREE PRODUCTION PROBLEMS (% OF RESPONDENTS) ......................................................................... 35

TABLE 35: OPPORTUNITIES FOR EXPANSION OF HORTICULTURAL CROPS PRODUCTION ................................................. 37

TABLE 36: MAJOR HORTICULTURE TRADED AT FINKILE MARKET AND OUTFLOW ........................................................ 39

TABLE 37: VEGETABLE MARKETING IN HARAMAYA MARKET ...................................................................................... 40

TABLE 38: PROPORTION OF VEGETABLES TRANSPORTED TO DIRE DAWA ..................................................................... 40

TABLE 39: MAJOR SUPPLY OF POTATO TO KOMBOLCHA MARKET ................................................................................. 41

TABLE 40: SUPPLY OF ONION ........................................................................................................................................ 42

TABLE 41: SUPPLY OF POTATO...................................................................................................................................... 43

TABLE 42: SOURCES OF SUPPLY OF HORTICULTURAL PRODUCTS TO CONSUMERS (%) .................................................. 49

TABLE 43: THE QUANTITY PURCHASED PER MARKET DAY IN KG .................................................................................. 49

TABLE 44: PURCHASING FREQUENCY AND QUANTITIES PURCHASED BY THE CONSUMERS (EASTERN TOWNS) .............. 51

TABLE 45: PROPORTION OF CONSUMERS WHO RANKED THE CONSTRAINTS OF PURCHASING THE RESPECTIVE

PRODUCTS AS THE TOP THREE PROBLEMS (%) ..................................................................................................... 52

TABLE 46: WHAT SHOULD BE DONE TO IMPROVE CONSUMPTION OF HORTICULTURAL PRODUCTS? .............................. 52

TABLE 47: PROPORTION OF RESPONDENTS WHO RANKED THE MARKETING PROBLEMS AS ONE OF THE TOP THREE

PROBLEMS (%) .................................................................................................................................................... 57

TABLE 48: AVERAGE MONTHLY CONSUMER PRICE OF HORTICULTURE PRODUCTS MARKETED AT HARAR MARKET

(SEPT. 2005 TO AUG. 2006) (BIRR PER KG) ......................................................................................................... 61

TABLE 49: MARKETING MARGIN (BIRR/QT) .................................................................................................................. 62

TABLE 50: PRICES OF MAJOR FRUITS AND VEGETABLES EXPORTED TO DJIBOUTI .......................................................... 63

v

List of Figures

FIGURE 1: COMPOSITION OF CONSUMERS BY INCOME SOURCE (%) ............................................................................... 11

FIGURE 2: TYPICAL CROPPING PATTERN IN EASTERN HARARGHE, EASTERN ETHIOPIA ................................................. 14

FIGURE 3: PROPORTION OF HOUSEHOLDS HAVING CROPLAND AND IRRIGABLE LAND ................................................... 18

FIGURE 4: TYPES OF SEEDS USED BY FARMERS TO PRODUCE HORTICULTURAL CROPS (N=128) .................................... 21

FIGURE 5: FARMERS' ASSESSMENT OF CHANGES IN VOLUME OF SALES OF HORTICULTURAL PRODUCTS........................ 23

FIGURE 6: POTATO YIELD (QT/HA) ............................................................................................................................... 25

FIGURE 7: INPUT SUPPLY CHANNEL............................................................................................................................... 30

FIGURE 8: MAJOR HORTICULTURE MARKETS AND FLOW IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA ............................................................ 38

FIGURE 9: MAJOR MARKET ACTORS ALONG THE MARKET CHANNEL ............................................................................. 45

FIGURE 10: TREND OF EXPORT OF HORTICULTURAL PRODUCTS .................................................................................... 48

FIGURE 11: CHANGE IN QUANTITY AND REVENUE ........................................................................................................ 48

FIGURE 12: AVERAGE PRICE OF POTATO AT KOMBOLCHA MARKET .............................................................................. 60

vi

ACRONYMS

AIQCI

AISE

ARDO

CATVC

DAs

DCG

ECC-SDCOH

ETFVMSC

FGD

IPC

MD

MOARD

MOTI

NGOs

OARD

PA

PRA

QSCAE

qt

USD

WARDO

ZARDO

Agricultural Input Quality Control and Inspection

Agricultural Input Supply Enterprise

Agriculture and Rural Development Office

Chiro Agricultural Technical and Vocational Training College

Development Agents

Drylands Coordination Group

Ethiopia Catholic Church Social and Development Coordinating Office of

Harar

Ethiopia Fruits and Vegetables Marketing Share Company

Focus Group Discussion

International Potato Center

Man days

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

Ministry of Trade and Industry

Non Governmental Organizations

Oromia Agricultural and Rural Development

Peasant Association

Participatory Rural Appraisal

Quality Standard and Control Authority of Ethiopia

Quintal (100 kg)

United States Dollar

Woreda Agriculture and Rural Development Office

Zonal Agriculture and Rural Development Office

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several people contributed to the successful accomplishment of this work. The management

of DCG Ethiopia in general and Mr. Abiy Alemu in particular were very helpful facilitating

the assignment. Staffs of CARE Ethiopia especially Ms. Komi Alemu and Mr. Asmare Ayale

were helpful in facilitating the logistic and the data collection process. The eastern Hararghe

and western Hararghe zone Agriculture and Rural Development Offices, Haramaya, Kersa,

Kombolcha, and Chiro Agriculture and Rural Development Offices, the Harari Agricultural

and Rural Development Office, Trade and Industry Development Agency, Dire Dawa

Agriculture and Rural Development Office, Quarantine and the Dire Dawa Customs Office

are among the many organizations that cooperated in providing the necessary data and

facilitated the data collection in their respective areas.

Without the willingness of the traders, farmers, consumers, middlemen, and experts to

respond to the questions, this work would not have been possible. Mrs. Hedija Mohammed

helped in the data analysis.

Mrs. Lauren Naville and Mr. Moti Jaleta read the draft report and gave useful comments

which helped to improve the report.

The authors appreciate their contributions and thank them all.

The authors

viii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The study was conducted in selected major horticulture producing woredas, namely

Kombolcha, Haramaya, Kersa (for vegetables) and Dire Dawa (for fruits). The study aims at

assessing the marketing channels, organizations, linkages and lines of movements of

horticultural products and production inputs to understand the major constraints of marketing

functions and opportunities to improve horticulture production and marketing.

The data collection was conducted in September 2006. A survey was conducted using

structured and semi-structured questionnaires to collect primary data from 141 producers and

95 consumers. Moreover, PRA tools were used to collect information from groups and key

informant producers, traders, transporters, exporters, institutions involved in extension, input

supply and marketing. The following provides a brief summery of the findings of the study.

Production:

Different types of vegetables are grown in the study area with different intensities in terms of

land and other input allocation, purpose of production, and marketability. The most

commonly grown vegetables in terms of the number of growers are Irish potato, cabbage,

onion, carrot and beet roots. Only 23% of the respondents (N=141) produce fruits. The

production is concentrated in the lowland areas. Most of the households have few plants often

grown for consumption although a limited amount is also sold. Vegetables provide the most

intensive production system where some farmers produce them in three cycles within the

same year. But two cycles are very common.

Irrigation water is crucial for horticulture production. Hence, most of the vegetable producers

rely on irrigation mainly to harvest their products during the dry season when the price is also

high. High fertilizer and animal manure intensity is used. Since the land size is small, the

fertilizer use intensity is high. About 31% of the vegetable producers used local varieties.

Improved varieties needed to produce the desired product are said to be unavailable.

Pesticides are used by some 33% of the sample respondents. About 74% of them acquired it

from known sources while some 11% purchased it from unknown sources. There are

observations of adulteration of inputs affecting germination qualities of seeds and efficacy of

pesticides.

Input supply system:

Improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides are supplied through different channels. Seeds and

pesticides are either collected from local producers or imported for further distribution.

Fertilizers are imported. The role of unions in importing and distributing inputs is growing.

Currently there are some 11 unions importing fertilizer. The regional governments deal and

facilitate input supply through the unions to member cooperatives and then to farmers. The

Ethiopian Agricultural Inputs Supply Enterprise (AISE) is a major public institution involved

in inputs importing, collecting and distributing through its branch offices at woreda level.

Traders also play a crucial role in supplying inputs.

Production constraints and opportunities:

The major horticulture production constraints include pests, drought, shortage of fertilizer,

and price of fuel for pumping water for irrigation. Lack of desired seed variety was also

stated. The opportunities for increasing horticulture production include the increase in market

integration, the need for intensive production in response to increasing population pressure,

farmers' awareness of the benefits, the current outreach program in relation to supportive

government policy, attempts made in water harvesting, etc.

ix

Horticulture marketing:

Vegetables and fruits are produced in some specific locations in the eastern part of Ethiopia

and supplied to the local markets and to the neighboring countries. The major markets

identified for collection and distribution of large volumes of vegetables are Haramaya,

Finkile, Harar, Kombolcha and Dire Dawa. The market actors namely producers, collectors,

brokers, transporters, traders, consumers, and exporters play different roles along the market

chain.

Irish potatoes and onion/shallot are the most commonly marketed vegetables accounting for

about 60 and 20% of the marketed products. The other products such as cabbage, beetroots

and carrot, garlic, green pepper, Baharo, lettuce and tomato are marketed at relatively smaller

quantities by few farmers.

The leafy vegetables are often supplied from the woredas within the eastern region to markets

in the eastern towns including Djibouti while relatively less perishable and highly demanded

vegetables such as Irish potatoes and onion, are also supplied from markets in Addis Ababa

and eastern Shewa zone of Oromia to these markets depending on the seasonal supply deficit

in the region.

The production is seasonal and price is inversely related to supply. During the peak supply

period, the prices decline. The situation is worsened by the perishability of the products.

Storage facilities are poor. Along the market channel 25% of the product is spoiled.

Farmers’ bargaining power is low due to the lack of alternative market outlet. The most

common marketing channel immediately available to the farmer is through brokers. There are

up to three brokers between the producer and the trader. Each of the brokers makes a known

margin of Birr 5-10 per quintal. The traders/wholesaler and the producer do not have any

contact in which case the broker is decisive in setting the price, often making his own margin

(unknown to both trader and producer). There is no norm or regulation governing the acts of

the brokers and their behavior negatively affects the farmers.

Every market actor makes its own market margin. Hence, the more the farmers organize

themselves and access the terminal market, the more they benefit.

Marketing problems:

The major constraints of marketing include lack of markets to absorb the production, low

price for the products, large number of middlemen in the marketing system, lack of marketing

institutions safeguarding farmers' interest and rights over their marketable produces (e.g.

cooperatives), lack of coordination among producers to increase their bargaining power, poor

product handling and packaging, imperfect pricing system, lack of transparency in market

information system mainly in the export market.

Informal transaction prevails in the export system. Producers and local traders receive value

for their products only after the exported product is sold. There is a lack of standard for

quality control and hence lack of discriminatory pricing system that accounts for quality and

grades of the products.

Recommendations:

Different recommendations are forwarded. The most crucial ones are organizing the traders

and the producers to work as partners. Building their business capacity and overcoming their

constraints and capacitating them to use market information are important. Putting the market

right through institutionalizing the marketing system, the commission agents' functioning,

x

grades and standards, improving the export system by improving the transparency in the price

setting and credit system are crucial interventions. Finally, the government should review the

export price, which is determined through negotiations.

xi

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1

BACKGROUND

More than 85% of the Ethiopian population, residing in the rural area, is engaged in

agricultural production as a major means of livelihood. However, the agricultural productivity

is low due to use of low level of improved agricultural technologies, risks associated with

weather conditions, diseases and pests, etc. Moreover, due to the ever increasing population

pressure, the land holding per household is declining leading to low level of production to

meet the consumption requirement of the households. Hararghe highland is one of the highly

populated areas in Ethiopia. As a result, intensive production is becoming a means of

promoting agro-enterprise development in order to increase the land productivity. Horticulture

production gives an opportunity for intensive production and increases smallholder farmers'

participation in the market.

The production of horticultural crops is a major element of the farming system of some of the

woredas1 in the eastern part of Ethiopia such as Fedis, Haramaya, Kombolcha, Kersa, Meta,

Kurfa Chelle, Grawa, Jarso in eastern Hararghe zone and some other woredas such as

Gemechis in western Hararghe zone, and Dire Dawa Provisional Administrative City Council.

In the areas where irrigation water is available and farmers have access to the market,

horticulture production is a major source of cash income for the households. Horticultural

products are supplied to the local markets and exported to Djibouti and Somalia. Horticulture

production and marketing is one of the major sources of livelihood for a large number of

farmers, transporters, middlemen and traders in the area.

The Ethiopian Rural Development Strategy document has given emphasis to market-led

agricultural development that will be achieved by establishing and implementing grades and

standards, improving the provision of market information, expanding and strengthening

cooperatives, and improving and strengthening private sector participation in the agricultural

system. The growing government support for market integration and agro-enterprise

development provides an opportunity for the horticulture growers and market actors. This

indicates that the government is using policy support as one of the mechanisms for creating

investment opportunities in the horticulture sector for production, transportation, grading,

exporting and financing the venture. It has been, however, witnessed that farmers are price

takers and the middlemen and exporters are major gainers of the business. Farmers are often

losers or receive a marginally low share of the price paid by the consumers for the

horticultural products.

The few studies available were made on few commodities such as potatoes and pointed out

that there is a greater need to diversify export earning options by improving the quality of

produces supplied to the export market and enhancing the efficiency of the marketing system

to contribute to the economic growth of the country. Nevertheless, little or no information is

available on how to do this and particularly on how to improve the life of poor producers by

increasing their share of the market price and enhance farm productivity.

In order to address these issues and generate further knowledge on the production and

marketing of horticulture in the study area and inform policy makers as well as use the

1

Ethiopia is a federal state of regions. Every region is administratively structured into zones and zones are

divided into woredas, which is similar to the district level administrative unit. Every woreda is divided into

Peasants Association (PA), which is the lowest administrative unit. The PAs are called kebeles in the urban

areas.

1

Drylands Coordination Group

knowledge gained as basis for designing local level development programs, this study was

commissioned by CARE Ethiopia and DCG Ethiopia to two national consultants (Dr. Bezabih

Emana and Mr. Hadera Gebremedhin).

The study was conducted in the major horticulture producing woredas and major horticulture

market centers in the eastern part of Ethiopia and the data collection was done in September

2006.

1.2

OBJECTIVES

The overall objective of the study was to assess constraints of maximum use of opportunities

in vegetable production and marketing in the eastern part of Ethiopia. The specific objectives

were:

1. To assess the marketing channels, organizations, linkages and lines of movements of

horticultural products and production inputs;

2. To assess major constraints of marketing functions (production, processing, grading,

buying and selling, transportation, storage, financing, etc.);

3. To analyze national and local government policies, strategies and practices related to

marketing and production of horticulture crops;

4. To identify and inform government, chambers of commerce and NGOs with possible

strategies that would support horticulture production and marketing to improve the

economy of the region and more specifically the income of poor farmers.

The first three objectives have been addressed in the study process and results have been

documented while the fourth objective involves continuous attempts and forums to

disseminate the results and advocate on how to overcome the constraints and make the

maximum use of the identified opportunities.

1.3

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The report is organized into 11 chapters. The first chapter provides background, objectives,

and organization of the report and limitation of the study. Chapter 2 describes methodology

on data collection and data analysis. Chapter 3 describes some characteristics of producers

and consumers. Chapter 4 deals with horticulture production covering farming systems, type

of horticulture crops produced, inputs used, production level, income from the sub sector and

profitability. Chapter 5 deals with the input supply system while chapter 6 assesses the

constraints and prospects of horticulture production. Chapter 7 deals with horticulture

marketing functions covering market centers, marketing channel, facilities/infrastructure,

constraints and opportunities for horticulture marketing. Chapter 8 discusses the prices of

fruits and vegetables. In chapter 10, gender disaggregated horticulture production and

marketing decisions are highlighted. Finally recommendation and conclusions are outlined in

chapter 11.

1.4

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Marketing of horticulture products in the eastern part of the country extends to markets in the

neighboring countries. The time and logistics budgeted for the study could not, however,

allow for an assessment of the markets in Somalia and Djibouti, which are the export markets

for fruits and vegetables. Thus, only a few key informants and secondary information have

been used as source of information to obtain preliminary information about the external

markets.

2

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

The secondary data collected at different levels sometimes show inconsistence. In this case,

the research team was forced to rely on grassroots primary data.

There is also administrative restructuring where some PAs and woredas are split, as it was the

case in Chiro woreda in west Hararghe zone. Since this is a new phenomenon, the structure

during the last production season was used.

3

Drylands Coordination Group

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1

DATA COLLECTION

The major vegetable producing woredas in Hararghe are Kombolcha, Haramaya, Kersa, Kuni,

Meta, Hirna and Jarso woredas. Kombolcha, Dire Dawa and Haramaya are serving as a

medium for both export and domestic vegetable marketing centers, because of their long

border with Somaliland and Djibouti and transport network (air, train and road).

The study was conducted in eastern Ethiopia during September 13 - 28, 2006 in selected

horticulture producing woredas and horticulture marketing towns/cities. A survey was

conducted in four sites, namely Haramaya, Kersa, Kombolcha and Dire Dawa to collect

primary information on production, marketing and consumption of horticulture products. The

four study sites were purposefully selected in consultation with the clients and concerned

Offices in eastern Hararghe, western Hararghe and Dire Dawa. The Hararghe Zone

Agriculture & Rural Development Office was instrumental for the selection of the major

vegetable suppliers since the woredas in eastern Hararghe are the major producers of

vegetables for marketing. Dire Dawa Provisional Administrative City Council Agriculture

and Rural Development Office were also consulted in the sampling of appropriate PAs for the

assessment of fruit production in the woreda.

The data collection intended to generate the necessary information along the horticulture

production and marketing channel/chain. Accordingly information about production potentials

and constraints, transportation, storage, product handling, prices, marketing systems and

constraints, consumption, etc. were collected. The data collection, therefore, required visiting

different actors along the marketing channel2. Accordingly, the primary data were collected at

three levels: from producers, consumers, and intermediaries. The following sub-sections

provide the tools used for data collection from the different sources.

2.1.1 Producers’ survey

A two stage sampling technique was used to select the producers. Firstly, in consultation with

the respective Woreda Agriculture and Rural Developments Offices, the PAs in each woreda

were clustered into two: horticulture producers and non-producers. Two horticulture

producing Peasant Associations (PAs) were randomly selected in each of the woredas.

Secondly, the sample farm households were randomly selected for the interview from the

selected PAs. It was originally planned to interview 40 farmers in each woreda, though it was

difficult to access the intended number in Dire Dawa Provisional Administrative City

Council3. Table 1 shows the specific study sites and the number of horticulture producers

included in the survey.

2

We chose to use the Marketing Channel when discussing the product flow between producers, market actors

and consumers. Since there is no value adding process as such in horticulture marketing in the study area, the

value chain analysis is not appropriate at this moment.

3

Farmers producing fruits in Dire Dawa woreda were suspicious of the land tenure system and did not want to

appear for the interview during the data collection period. Those found were convinced about the purposes of

the study and cooperated to provide the necessary information.

4

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

Table 1: Distribution of sample horticulture producers included in the survey

Sr.

No.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Kebele

Chefe

Anani/Walta'a

Lammi

Bilisumma

Finkile/Bate

Ifa-Oromiya

Kosum/Burqa

Jalala

Metaqoma

Bishan Bahe

Lega Dol/Lega

Harree

Total

Kombolcha

Source: Own sampling (September 2006)

Woreda

Haramaya Kersa

20

20

Dire Dawa

20

20

20

19

20

19

20

20

40

39

Total

40

10

20

20

10

12

22

12

141

Structured and semi-structured questionnaires and checklists were used to collect data from

producers and consumers. The survey questionnaire was administered by experienced and

qualified enumerators employed from Haramaya University. The producers' questionnaire

includes questions relevant for assessment of production potential, input use, constraints of

production, marketing extent of horticulture products, market centers, marketing agents,

pricing, packaging, transportation and associated cost, marketing problems and potentials

perceived by the producers, etc. (see Annex 1).

2.1.2 Consumers’ survey

Consumers were interviewed in major towns along the horticulture marketing channel,

namely Haramaya, Kersa, Kombolcha, Harar and Dire Dawa. The consumers were selected

based on systematic random selecting technique. Firstly, the kebeles in the town were

randomly selected and then respondents were systematically randomized in such a way that

the enumerators were guided and visited to the residences of the respondents at fixed intervals

and interviewed 20 households per kebele. The major purpose of the consumers’ survey was

to get an impression of local consumption of horticultural products and assess constraints

associated with consumption so that possible interventions for improvement of horticulture

production and marketing can be identified. In total 95 consumers were interviewed using a

structured questionnaire (see Annex 2) of whom 74% were female. The fact that the

household activities including purchasing and cooking of food is mainly the responsibility of

women and girls, the high ratio of female respondents reflects the reality on the ground. Table

2 shows the distribution of respondents by sex and town.

Although some farmers also purchase horticultural products, which they do not produce,

emphasis was given to urban dwellers. The sample size is proportional to the size of the

town/city where population is taken as an indicator of size. Accordingly, the sample size is

larger for bigger towns (42% for Dire Dawa), 24% for Harar, 16% for Kombolcha, 11% for

Haramaya and 7% for Kersa.

5

Drylands Coordination Group

Table 2: Number of consumers included in the survey by sex

Location

Haramaya

Dire Dawa

Kombolcha

Kersa

Harar

Total

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

Sex of the respondent

Male

Female

4

6

9

31

6

9

1

6

5

18

25

70

Total

10

40

15

7

23

95

2.1.3 Focus group discussion

Besides the primary data collection from producers and consumers, general information about

the production potential, constraints, marketing channels, marketing functions and constraints

were assessed in the intensive focus group discussions using a detailed checklist prepared for

this purpose. Focus Group Discussions (FGD) and key informant interviews were made with

groups and community leaders, key informants, and knowledgeable people on the subject in

the study areas covering five woredas in both eastern and western Hararghe zones of Oromia

Regional States, Dire Dawa and Harari Regional State. The discussions were held with elders,

youth, and women farmers, and responsible persons of different institutions. Moreover, the

data generated in collaboration with experts at various levels was supported by field

observations. Furthermore, FGD were conducted with traders, transporters, brokers, etc. in

Dire Dawa, Harar, Haramaya, Kersa, Kombolcha, Finkile and Chiro towns. From the 51

participants of the FGD, 39 were involved in production while 12 were involved in marketing

(see Annexes 3 and 4).

Furthermore, six exporters were contacted in Dire Dawa where they were clearing and

loading their products to Djibouti and three other wholesalers at Kafira market in Dire Dawa

were also approached to discuss marketing of vegetables and fruits.

2.1.4 Secondary data

Additional data were also collected from secondary sources. Different offices such as the

Agriculture and Rural Development Offices of the zones and woredas, Micro and Small Scale

Development Enterprise, Trade and Industry, Customs Office, etc. in Dire Dawa were major

sources of secondary data. Time series bid price information was also collected from

Haramaya University to understand the trends in vegetable prices. The Dire Dawa Plant

Quarantine, Federal Seed Agency, Horticulture Development Enterprise, and Ethiopian Fruits

and Vegetables Marketing Share Company, and Quality Standard and Control Authority of

Ethiopia have all provided information on the subject.

2.2

DATA ANALYSIS

The data collected from primary sources were coded and entered into SPSS computer

software. The data were checked for consistence and completeness and analyzed.

Frequencies, cross-tabulations, means and ratios were computed. Moreover, factors

determining the productivity of major horticultural crops and marketed volumes of

vegetables, price situations, etc. were computed. The following chapters present the results of

the analysis.

6

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

3. SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RESPONDENTS

3.1

PRODUCERS

3.1.1 Demographic features

Age and sex composition are the major demographic features used to characterize the

producers. Although efforts were made to account for gender representation, the actual

random sampling resulted in only 2 female headed households from the 141 sample

producers. But attempts were made to interview the household head in the presence of his

spouse so that the responses account for the views of the women. In the study area (eastern

Ethiopia), men are often responsible for farm work and the woman has the major

responsibility in the reproductive tasks, marketing of smaller quantities of farm products and

purchase of food and non-food items for consumption.

The respondents' age ranges from 16 to 68 with an average of 38 years. About 24% of the

producers fall below 30 years and 50% of them are more than 40 years old. The respondents

have an average of 17 years of experience in horticulture production (ranging from 2 to 50

years) and hence could provide information related to the constraints and potentials of

promoting the horticulture sector.

The horticulture production system is often intensive and requires more labor for cultivation

than the cereal production does. The household provides a major source of labor for crop

production. The labor available for work per household is directly proportional to the family

size. The family size of the respondents ranges from 1 to 13 with an average of 7. On average

43% of the household members are able to work (Table 3). Accounting for children below 16

and elders of above 60 years as dependents4, the dependency ratio was calculated. The results

show that 57% of the households depend on the active labor force of the household since they

are unable to take part in the income generation process.

Table 3: Average household size and dependency ratio

Household size

Working members

Woreda

Male Female

Total*

Male Female Total*

Kersa

4.03

3.51

7.45

1.78

1.28

2.89

Kombolcha

3.97

3.64

7.36

1.67

1.69

3.00

Dire Dawa

3.19

4.14

7.33

1.52

2.12

3.05

Haramaya

3.33

3.23

6.33

1.82

1.77

3.18

Total

3.69

3.57

7.09

1.72

1.66

3.03

* Weighted average and accounting for intra household gender differences

Dependency

ratio

0.61

0.59

0.58

0.50

0.57

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

In terms of the marital status of the producers, 93% of all the sample respondents were

married while about 4.5 and 2.2% of them were unmarried and widows respectively. There

are no significant differences among the sample respondents in terms of age, sex and marital

status (Table 4).

4

Although some children below 16 years of age are involved in farming, they significantly contribute to herding

rather than cultivation per se.

7

Drylands Coordination Group

Table 4: Marital status of the household heads by woreda

Woreda

Kersa (N=40)

Kombolcha (N=40)

Dire Dawa (N=22)

Haramaya (N=39)

Total (N=141)

Married

92.31

100.00

95.45

86.49

93.28

Unmarried

5.13

4.55

8.11

4.48

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

Widowed

2.56

5.41

2.24

Total

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

3.1.2 Education

Education is a crucial factor for skill development and enhancing effective production and

marketing decisions. The survey shows that 58% of the producers do not have formal

education while about 16% attended high school level education. The smallest proportion of

those who attended high school level education is found in Haramaya woreda (Table 5).

Table 5: Level of education of the household heads by woreda

Education Level

No formal education

Primary education

Secondary

Total

No. of respondents

Kersa

60.0

22.5

17.5

100

40

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

Kombolcha

65.0

20.0

15.0

100

40

Woreda

Dire Dawa

45.5

31.8

22.7

100

22

Haramaya

56.4

33.33

10.3

100

39

Total

58.2

26.2

15.6

100

141

As children share information with parents, the knowledge gained in school is instrumental in

influencing parents' decisions. The importance of education is getting momentum whereby

82% of the respondents have at least one child attending school with an overall average of

about 3 children per household attending school (Table 6). Education is an instrument for

bringing about attitudinal change and enabling girls to take part in making decisions affecting

their future.

Table 6: Average No. of children in school per sample household

Woreda

Kersa

Kombolcha

Dire Dawa

Haramaya

Total

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

Male

2.6

1.5

1.6

2.0

2.0

No. of children in school

Female

1.8

1.7

1.9

1.5

1.7

Total

3.2

2.7

3.3

2.2

2.8

3.1.3 Means of livelihood

The respondents depend on different means of income generation strategies. Crop production

is a major source of income for the majority of the producers. About 96% of the respondents

earn their living from horticulture production as a primary source. Grain and legume crops

production is considered as the second major means of livelihood of the producers. The area

that does not have any irrigation possibility is allocated to maize, sorghum and haricot beans.

Khat (Catha edulis) or coffee production takes the 3rd and 4th rank respectively in terms of

the number of households that depend on them as a means of livelihood (Table 7). This shows

8

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

that the study sites are appropriate for the assessment of horticulture production and

marketing constraints.

Livestock production is limited by the shortage of grazing area and hence by critical shortage

of feed. Only 44% of the sample respondents have oxen, which is 1.6 on average. Cattle are

reared for milk production, which is an important dietary source in the hoja5. On average

there are two cattle of which at least one is a milking cow per household. Moreover, there are

about 3 sheep and 3 goats per sample households though only 42% of the respondents own

sheep and 65% own goats.

Farmers also participate in off-farm activities to generate supplementary income during slack

production seasons. Petty trade is a major off-farm activity. The participants of such trading

activity could make an average income of Birr 59 per market day. About 10% of the sample

producers stated that they participated in off-farm income generating activities. Among the

respondents, only 3% make subsidiary earnings from trading of Khat and vegetables.

Table 7: Major means of income generation of the horticulture producers

Income sources/livelihood strategies

Frequency

Percent

136

92

68

66

96.5

Horticultural production

Grain and pulse production

Livestock production

Khat /coffee production

Income generating activities such as

retailing and flour mill service

Khat trading

7

3

Horticulture trading

Total

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

3.2

65.2

48.2

46.8

5.0

1

2.1

0.7

141

100

Relative

importance

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

CONSUMERS

As stated above, 74% of the respondents are females that are involved in the purchase and

preparation of vegetables. The respondents are adults of ages ranging from 22 to 74 years

with an average of 37. The consumers have an average of 21 years (minimum 4 and

maximum 67 years) of experience in purchasing fruits and vegetables for consumption.

3.2.1 Demographic features

The household size determines the volume of purchase of horticultural products. The average

family size of the consumers is 5 persons and ranges from 1 to 13. On the other hand, the

purchasing capacity of the household depends on the income the household generates. In a

labor based household economy where the income of the household depends on the labor

availability, the number of able family labor determines the income level. The survey result

shows that for every one working person there is a minimum of one dependent person. The

number of female members of the household is only slightly higher than the number of male

members, which is consistent with national statistics.

5

Hoja is a stimulant drink prepared from coffee pulp or leaves to be used like tea when chewing Khat.

9

Drylands Coordination Group

Table 8: Consumers' household size and family labor availability

Sr.

No.

1

2

Number of members in the household

Male members of the household

Female members of the households

N

95

95

Minimum

0.00

1.00

Maximum

7.00

6.00

Mean

2.51

2.71

3

Total family size

95

1.00

13.00

5.19

4

Male working persons in the household

Female working persons in the

household

95

0.00

6.00

1.23

95

0.00

4.00

1.17

Total number of working persons

95

0.00

9.00

2.40

5

6

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

With regard to the level of education of consumers, the survey result shows that about 43% of

the respondents attended education until secondary school or the level above. On average, the

sample consumer household has two children attending school, with insignificant difference

between the number of school boys and girls.

Table 9: Level of education of the household head (consumers)

Level of Education

No formal education

Primary education

Secondary

Collage level (Diploma)

University level (Degree)

Total

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

No. of respondents

21

33

32

8

1

95

Percent

22.1

34.7

33.7

8.4

1.1

100.0

3.2.2 Means of livelihood of the consumers

The urban consumers earn their income from different sources and the purchasing power of

the consumer depends on his/her income level. Figure 4.1 shows the composition of the

consumers included in the survey. The largest proportion of the respondents (48%) earns its

income from employment while the next largest proportion earns it from trading. About 8%

of the sample includes consumers who earn their income from skill based activities such as

mechanics, drivers, etc. Some three percent of the consumers are also involved in farming

although they are urban/town dwellers.

10

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

Figure 1: Composition of consumers by income source (%)

Renting

houses

2%

Other means

(skill based)

8%

Farming

3%

Trade

39%

Employment

48%

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

In Hararghe, vegetables are commonly used as part of the diet. Onions, potatoes, carrots,

tomatoes and cabbage are consumed even by poor households at different intervals. The

consumers were asked to estimate their monthly/annual income and the proportion of income

they spend for the purchase of horticultural products. The result shows that the average annual

income per household is Birr 11,841, which means that the per capita income is about Birr

2,370 (USD 272). There is, however, a difference in income level of the sample consumers in

different towns/cities which increases with the size of the town/city (Table 10). On average

about 10.5% of the income is spent for horticulture consumption.

Table 10: Annual income and its proportion allocated for the purchase of horticultural

products

Location

Haramaya

Dire Dawa

Kombolcha

Karsa

Harar

Weighted average

No. of

respondents

10

41

15

6

23

95

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

Mean income

(Birr per year)

12,728

13,352

13,820

4,655

9,344

11,841

11

Proportion of income used for

consumption of horticulture (%)

12.0

9.6

12.3

17.5

8.2

10.5

Drylands Coordination Group

4. HORTICULTURE PRODUCTION

In Ethiopia, vegetables and fruits are produced in smallholders and some state-owned farms.

The lion share in terms of area and produce comes from the smallholder sector. According to

MOARD (2005), about 99% of the area allocated to horticulture production is cultivated by

smallholders, which produced 428,752 tons of fruits and 2,107,292 tons of vegetables. The

total share of smallholders' produce during 2003 was 97% of the national supply. It is reported

that in 2004 about 45,0392ha of land was used for vegetable and fruit production which is

0.05% of the total area under cultivation, while in 2003 the total production of vegetables and

fruits was 24,526,712 qt.

4.1

FARMING SYSTEM IN THE AREA

The farming system in both highland and lowland areas is mixed farming. Farmers produce

different crop enterprises in order to secure their family food supply and also cover various

household expenses. Keeping animals in their homestead to provide feed by the cut and carry

system is commonly practiced in the highland areas where the farmland is small. The

production system in the study area can be described in two ways, i.e., rain-fed and irrigated

systems. The rain-fed production system is most dominant and is practiced by the majority of

the farmers in the study area. Farmers mostly produce potato, sweet potato, and local cabbage

together with cereals. The horticultural crops are often produced using irrigation.

Intercropping is also practiced by farmers to grow two or more crops simultaneously on the

same land. The crops may or may not be planted or harvested at one time. Intercropping has

numerous advantages such as:

• Greater stability of yield over different seasons;

• Increased fertility of the soil;

• Better use of resources;

• One crop provides physical support to the other crop;

• Erosion control through providing continuous leaf cover over the ground surface.

In addition to this it serves as insurance if in case one crop fails since different crop varieties

have different merits in terms of tolerance to diseases, pests, moisture stress, etc. The system

is very good for small farmers owning limited land area as they can produce two or more

crops on the same piece of land they own. The findings of the study reveal that only 12% of

the horticulture producers intercropped vegetables with other crops during the last production

year. This is due to the small area allocated to vegetable production, economic use of

irrigation water and expected high yield for cash generation. On the other hand, different

parcels of the same plot are allocated to different types of vegetables and fruit trees, which are

intercropped with other horticultural crops. The vegetable production system depends on

several factors such as the land size, availability of water, existence of adequate market

demand, and availability of inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, etc.

Eastern Hararghe has different geographical and ecological conditions. For instance, in the

relatively highland areas of Jarso, Deder, Haramaya and Meta, the farmers plant potato and

sweet potato during the short rainy season (early March) and harvest it in early June so that

the land will be used for the long season cereal crop production (wheat, barely, oat, and other

legumes). In areas where there is irrigation water in the two main production seasons (MarchJune) and meher (June to September), vegetables are produced during the dry season on land

used for cereals and other crop production as rain-fed. In areas like Haramaya, Kombolcha

and Kersa, vegetable production is determined by the market situation.

12

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in eastern Ethiopia

Double cropping is the production of two crops on the same plot of land in a year. Such a

practice is possible in the study area due to the bimodal nature of the rain. The farmers

produce the first crop during the short rainy season in February/March (1st cycle) and harvest

it in June/July and plant the 2nd crop in June/August to harvest it in October/November. Some

farmers indicate that they could produce vegetables in three cycles during a year. But the

technical production requirement indicates that crop varieties should be synchronized in order

to use the land three times a year (See Figure 2).

The extent of the third cropping is very low in the low land areas due to a very short growing

period and uncertainty of rainfall during the short rainy season. In some of the study woredas,

farmers use irrigation either to supplement certain crops or use irrigation throughout the dry

season of the year. Under such circumstances, a limited 3rd cycle of production may be

possible. The notion of increasing crop intensity requires a strong technological improvement

through research so that short cycle varieties are introduced. Table 11 shows the extent to

which farmers practice double/multiple cropping in vegetable production.

Table 11: Area allocated to vegetables during the different production cycles

Vegetables

Cabbage

Beetroots

Carrots

Onion

Irish potato

Tomatoes

Baharo

All vegetables

Cycle I*

Area

N

(Qindi)+

38

0.39

24

0.35

20

0.41

36

0.88

87

1.09

10

0.65

6

0.37

119

1.51

N

36

25

22

19

57

3

8

84

Cycle II**

Area

(Qindi)+

0.42

0.44

0.47

0.50

1.33

1.00

0.33

1.62

Cycle III***

Area

N

(Qindi)+

8

0.57

7

0.47

5

0.31

4

0.56

24

0.99

3

32

0.42

1.20

* Feb./March to May/June; ** July/August to October; *** November/December to January/February

+ 1 Qindi = 0.25 ha

Source: Own survey (September 2006)

The results show that cabbage, onion, potato, carrot and beetroot are the most commonly

grown vegetables during the two cycles. On average 0.35 ha of land is allocated to vegetable

production during the two cycles and helps increase land use intensity. The first cycle which

involves planting of vegetables in February/March requires irrigation supplementation while

the third cycle indicated by the farmers starts from October/November and depends entirely

on irrigation.

13

Drylands Coordination Group

Figure 2: Typical cropping pattern in eastern Hararghe, eastern Ethiopia

Type of crops

Jan.

Quarter I

Feb.

March

Sorghum /maize

April

Quarter II

May

Quarter III

June

July

Rain-fed system

Vegetables

August

Sept.

Oct.

Quarter IV

Nov.

Dec.

2nd cycle

Crops

Onion/potato

Sequence of vegetable production with irrigation (3 cycles)/year

1st cycle

Beet roots

Carrot/cabbage

3rd cycle

3rd cycle

Free

Source: Own survey (September, 2006)

14

Constraints and Opportunities in Horticulture Production and Marketing in Eastern Ethiopia

4.2

TYPES OF HORTICULTURE PRODUCED IN THE AREA

4.2.1 Vegetables

Different types of vegetables are grown in the study area with different intensities in terms of

land and other input allocation, purpose of production, and marketability. The most

commonly grown vegetables in terms of the number of growers are Irish potato, cabbage,

onion, carrot and beetroot (Table 12). As a result, emphasis is given to these vegetables for an

in depth analysis.

Table 12: Proportion of households producing vegetables (2005/06 production year)

Sr. No.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Crops

Irish potato

Cabbage

Onion

Carrots

Beetroots

Tomatoes

Baharo

Kale

Pepper

Lettuce

Sweet potatoes

Sample size

Source: Own survey (September, 2006)

No. of producers

118

48

43

34

34

12

11

9

8

7

2

141

Percent

83.7

34.0

30.5

24.1

24.1

8.5

7.8

6.4

5.7

5.0

1.4

100.0

Relative importance

1

2

3

4

4

6

7

8

9

10

11

4.2.2 Fruits

Only 23% of the respondents (N=141) produce fruits. The production is concentrated in the

lowland areas. Some of the respondents grow 1-4 different types of fruit trees while others

have none. Papaya is relatively widely grown followed by mandarin, gishta and orange. Most

of the households have few plants often grown for consumption although a limited amount is

also sold. The production is based on gardening (for non-irrigated) and field level production

under the irrigated system. About 52% of the fruit producers use irrigation, mainly in the Dire

Dawa area. Table 13 shows the number of farmers owning fruit trees and the number of plants

owned.

A good quality species of papaya was introduced to the Dire Dawa area through the

government extension system. The buyers also confirmed that the quality of the newly

introduced papaya is preferred. The output is appreciated by the producers since a papaya tree

produces 75-150 fruits attracting a good price of Birr 1.00 per piece. In the highland area, the

Hararghe Zone Agriculture & Rural Development Office is striving to expand fruit production

such as mango and other fruits conducive for highland areas.

15

Drylands Coordination Group

Table 13: Number of fruit trees per household

Sr.

No.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Type of fruit

Orange

Mandarin

Mango

Papaya

Gishta

Guava/Zeituna

Banana

Peaches

Others

No. of

respondents

No. of

producers

8

10

7

16

8

2

1

1

2

% of HH

24

30

21

48

24

6

3

3

6

33

100

Minimum Maximum

number

number

3

70

15

100

2

15

2

100

1

15

3

5

10

10

1

1

8

30

Mean

38

59

7

39

4

4

10

1

19

Source: Own survey (September, 2006)

Due to the small number of producers of fruits, a detailed production related analysis was not