/ç /7 Date thesis is presented

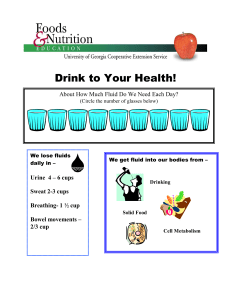

advertisement