Document 12836819

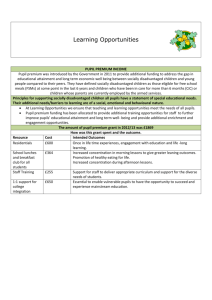

advertisement