The Costs and Benefits of Different Initial Teacher Training Routes

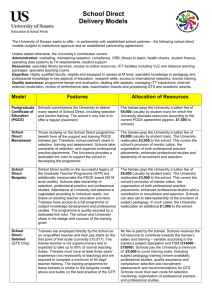

advertisement