This program deals with portions of the International codes’ prescriptive requirements for wood construction. Typically these provisions address what is often referred to as

advertisement

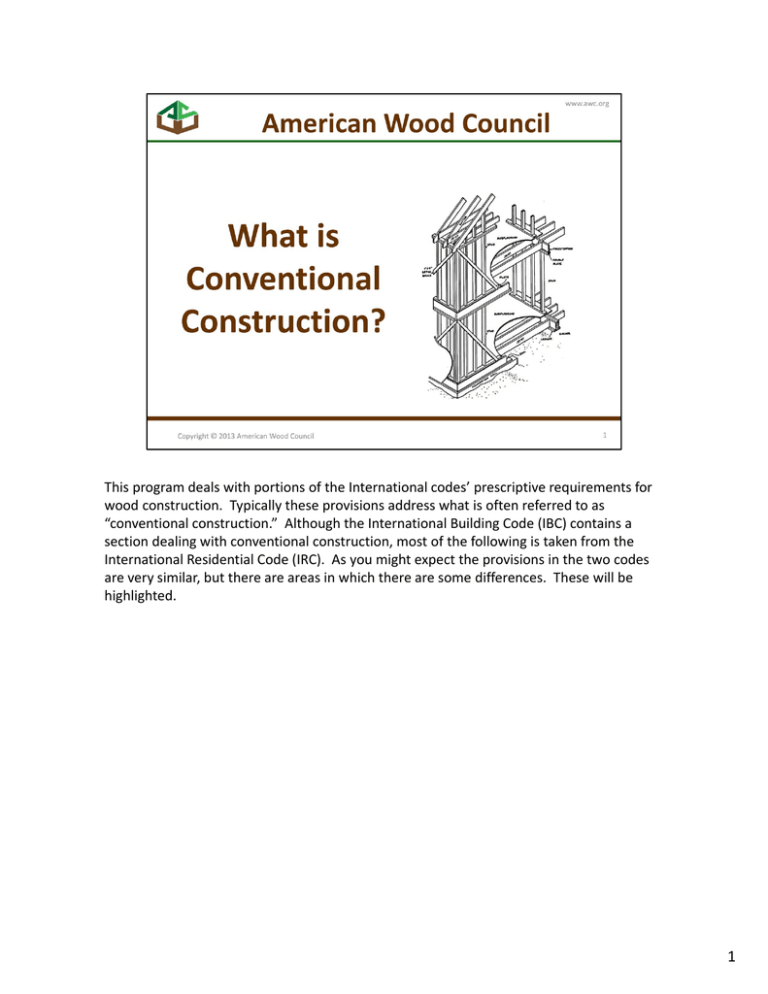

This program deals with portions of the International codes’ prescriptive requirements for wood construction. Typically these provisions address what is often referred to as “conventional construction.” Although the International Building Code (IBC) contains a section dealing with conventional construction, most of the following is taken from the International Residential Code (IRC). As you might expect the provisions in the two codes are very similar, but there are areas in which there are some differences. These will be highlighted. 1 Although this program is centered on the IRC, let’s look at how the IBC addresses wood design. In Chapter 23 of the IBC four methods of wood design are recognized – allowable stress design, load and resistance factor design, conventional construction, and provisions of ICC 400 for log structures. Conventional construction is specifically called out as one of those methods. 2 Here is the IBC definition of the term, although it’s somewhat different than just “conventional construction,” and a summary of the limitations for buildings that are constructed in accordance with the provisions of conventional light‐frame construction are listed here. 3 Although the conventional construction provisions in Ch. 23 of the IBC appear to address primarily residential uses, Section 101.2 of the IBC places most dwellings under the provisions of the IRC. Notice the exception to the scope of the IBC says that dwellings SHALL comply with the IRC. Therefore, conventional construction in the IBC 2308 would apply to those dwellings that might fall outside of the scope of the IRC for some reason and also includes portions of nonresidential buildings that fit within the limits of conventional construction as addressed in Chapter 23. 4 The IRC doesn’t define the term, “conventional construction”, however the term is used in the IRC and it’s scope tends to establish the limits of this methodology as permitted by that code. An expansion of the scope of the IRC seen in the 2012 edition is making it applicable to both live/work units (as defined in the IBC) and owner‐occupied lodging houses. See exceptions 1 and 2 of R101.2. 5 The basis of conventional construction is not from engineering analysis, but rather is from historic methods of construction using wood members. These methods have displayed a reasonable level of performance over decades. It’s important to realize that the original structures from which this method of construction was derived were relatively small, with small horizontal spans and moderate wall heights. The floor plans for these buildings were typically rectilinear. Also the loading on the buildings was consistent, and the materials used were familiar and their limits well understood. 6 Even when larger versions of these early buildings were constructed, the basic structural forms of the buildings were simple. 7 It’s important to remember that conventional construction – not engineering‐based prescriptive methods of construction such as are contained in AF&PA’s Wood Frame Design Manual – aren’t really intended for high loads. In fact both limits the use of it’s provisions to low‐wind areas. 8 For high‐wind areas, both codes references the readers to other methods of design, one of which is using the AWC Wood Frame Construction Manual. The program will talk about that document later. 9 Unlike the wind‐related portions of the code, the codes permits some prescriptive design of structures in high‐seismic (earthquake) areas. There are some limits, however, on building configurations. If the buildings are outside the scope of the IRC, they can be engineered or designed in accordance with the WFCM. 10 The IRC and IBC 2308 permits mixing of professionally designed elements with conventional construction. 11 We’ve talked a little about what conventional construction is – at least within the limits of the IBC and IRC. But what’s important to keep in mind is what conventional construction ISN”T. 12 Although the codes, particularly the IRC and IRC 2308, address general framing requirements, it doesn’t address situations like these in which concentrated loads are placed on beams or headers. In conventional construction, it assumes beams and headers are uniformly loaded. 13 Very large wood buildings may have some elements that could be conventional construction – interior nonbearing walls for instances – but these types of buildings are beyond the scope of conventional construction. And state engineering practice acts may require professional design. 14 Heavy timber structures are beyond the scope of the IRC and IBC 2308. 15 Engineered wood products such as glued‐laminated beams, which are common as headers and beams, aren’t addressed in conventional construction although their use is permitted. These types of products shouldn’t be treated like solid‐sawn lumber. 16 Trusses require professional design and the way that they connect to the rest of the structure should be closely examined. No changes should be made to these members without professional approval. 17 Other engineered wood products are also professionally designed and their use should be in compliance with the formal design and with the manufacturers’ recommendations. 18 To emphasize the fact that engineered wood products are special elements and shouldn’t be altered the code specifically addresses that situation. IRC R502.8.2 (floors) & R802.7.2 (roofs) prohibit alteration of EWPs unless specifically permitted by manufacturer’s recommendations or considered in the design of the member 19 And some things are just too abstract to be considered as conventional construction. 20 21