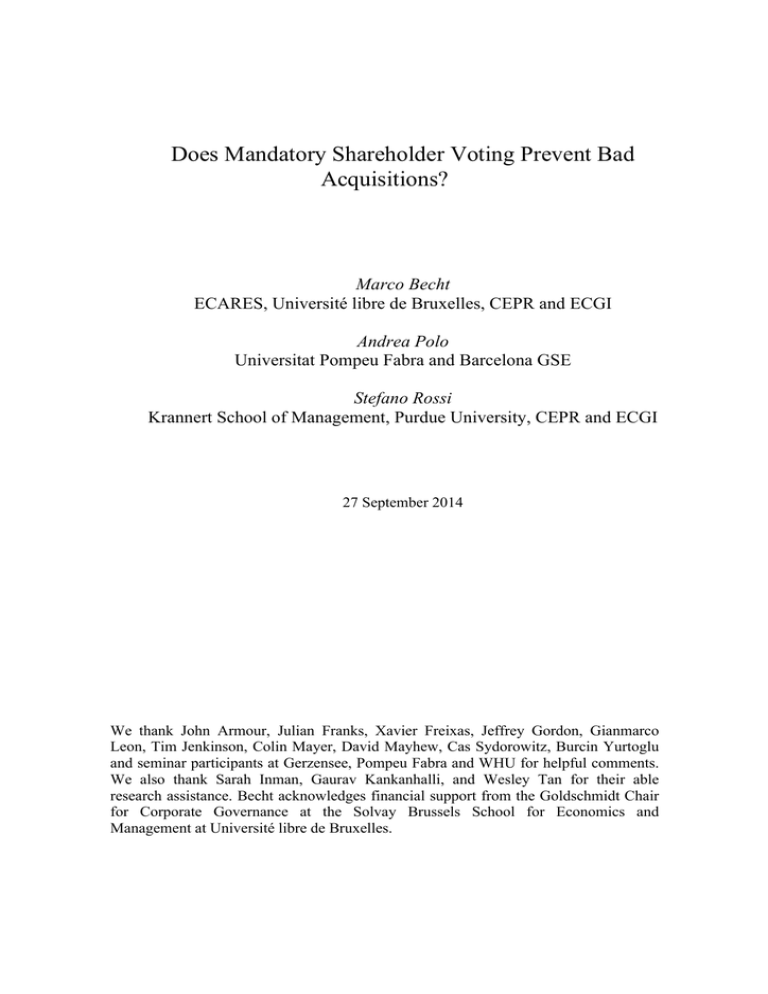

Does Mandatory Shareholder Voting Prevent Bad Acquisitions?

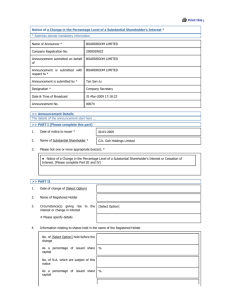

advertisement