Decent Homes Better Health Sheffield Decent Homes Health Impact Assessment

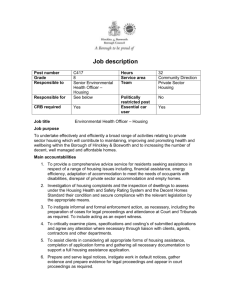

advertisement