Net Costs of Modern Apprenticeship Training to Employers R

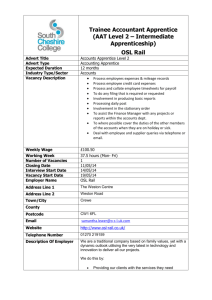

advertisement