Williams, Peter Greenfield, John Finney, Heping Liu, Greg Elliott, Yvonne... Roundy Academic Standards Committee Minutes

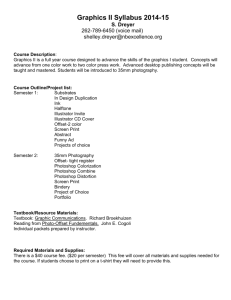

advertisement

Academic Standards Committee Minutes February 24, 1999 Present: Ken Clark, Brad Tomhave, John English, Susannah Hannaford, Marianne Taylor, Wade Williams, Peter Greenfield, John Finney, Heping Liu, Greg Elliott, Yvonne Swinth, Tom Gething, Jack Roundy 1. Minutes: The minutes of the February 10 meeting were approved with a correction of the spelling of Yvonne Swinth’s name. 2. Announcements: Roundy solicited feedback on likely faculty interest in an April 8 teleconference entitled “Reclaiming Civility in the Classroom,” produced by Dallas Telelearning and distributed by PBS. Dean Kay had offered support in putting on this event. Committee members did not believe incivility was a serious enough problem at Puget Sound to warrant hosting this program. 3. Petitions Committee: Tomhave submitted the following report without elaboration: Date Approved 2/11/99 2/18/99 YTD 23 5 180 Denied No Action Total 4 1 23 0 2 2 27 8 205 4. Re-examine the Idea of an Ethics or Honor Code for the University: Summarizing the discussion to date, English noted four issues of interest to the committee: 1) what forms of academic dishonesty require our attention (A. Wilson’s teaching guide focuses on plagiarism, but we’ve also discussed academic honesty issues related to science classes, and Bob Steiner has suggested that we attend to the new problems posed by the internet); 2) what possibilities there are for us to educate students about academic honesty issues in the classroom (e.g., through freshman seminars as proposed by Greenfield); 3) how we maintain currency of student and faculty knowledge of our policies (through periodic reminders?); 4) encouragement of faculty use of policies in place to address offenses (what should faculty do when faced with an offense? can faculty trust that they will be supported when they impose penalties?, etc.) Most of this day’s attention was given to #4. Clark distributed a summary of his inquiries of 11 members of the Geology, Physics, Chemistry and Biology faculty. Only 3 of 11 felt there would be some usefulness to general University guidelines to reduce cheating in science labs; the majority preferred to set and enforce their own guidelines, which they believed differed from colleagues’. While 4 of 11 felt no reluctance to report cheating, 7 were very reluctant, primarily over concerns about the harshness of the penalties that would ensue. Here Clark opined that more faculty would report cheating if they were aware that first offense reports are kept confidential and that the decision on penalties for those offenses is left with them. Finney pointed out that faculty reporting cheating usually don’t know if they are reporting a first offense; precisely because second and subsequent offenses merit more severe responses it is crucial that offenses be reported, so the behavior of serial offenders can be interrupted. Clark also asked his 11 respondents what assumptions they had about the reporting process. Two felt they understood the process well, 4 felt ill-informed, and the remainder had certain piecemeal assumptions. To the question “how many times do you think academic dishonesty has happened,” Clark received a variety of responses; no one felt cheating was widespread, but only one noted that he had never encountered a case. A fairly common response was that more students cheat than are caught. And of all instances known to these 11 faculty, only one case was ever reported according to policy. Reluctance to report among these faculty could not be attributed to a perceived lack of administration support, however, since the majority believed they would be supported if they brought a case forward, and only one felt fairly sure he would not be. English reported his inquiries of four colleagues. He collected these responses: a) are you aware of the policy? - yes; b) do you have confidence in the administration? - yes; c) do you feel you would be supported if you brought a case? - yes (though none had used the process). In each case, English’s colleagues said that if cheating occurred, they would see it as a counseling opportunity, and would handle it with the students themselves. None has ever needed to move the process up the reporting chain. English also collected comments, one of which was Steiner’s observation about the internet as repository for plagiarizable materials. The other was a suggestion that well-crafted paper assignments can defeat plagiarism by design; making a paper personal and setting up the process by which it is written carefully can make the submission of a plagiarized paper virtually impossible. Swinth reported making inquiries of her colleagues, the chief of whose concerns seemed to be that a reported offense might “dog” a student ever after. Her colleagues trusted in administration support if they reported an offense. One colleague had become gun-shy about the process nonetheless because of a case in which a student she reported requested a Hearing Board. The process took an enormous amount of her colleague’s time, and the colleague was nonplussed at facing off in the Hearing Board against the student and the supporter the student was allowed to bring along. Though the Hearing Board’s decision was satisfactory, the process was hard on her. Gething wanted to make it clear that the Hearing Board is not an administrative creature, so it may be misleading to cast the issue in terms of administrative support. In fact, the Hearing Board includes academic and student affairs deans’ representatives, but is balanced with faculty and student representatives, as well. Moving to a more general discussion, Greenfield advocated that we do a better job publicizing the difference between first offense responses and second offense responses, as he didn’t believe that was well understood around campus. Finney proposed that the ASC might sponsor an annual reminder to faculty about our policies (the ASC chair could be author, and could distill policy into its most salient points). English agreed, in fact, to take a crack at drafting such a reminder. Elliott wondered whether such a reminder would make much difference, citing his own habit of recycling general informational memos and emails of that type. He thought it might be more effective to have chairs sit down with younger colleagues and explain how the process works. Gething advocated multiple means of communication: a) email reminders; b) faculty “boot camp” presentations (Finney reported that he already covers academic honesty policy briefly at boot camp); c) department chair reminders in department meetings. Greenfield thought that timing was important, recommending that reminders go out shortly before midterm, when a lot of assignments come in and faculty are getting ready to post midterm grades. Hannaford made two points. First, she advocated telling faculty to be savvy as they craft assignments to avoid cheating. Second, she reported Biology faculty frustration with offenders who aren’t caught (those who steal exam keys, for example); such students don’t offer faculty many counseling opportunities. Williams noted that writing assignments requiring multiple drafts are effective in deterring plargiarism. Elliott replied that the sheer volume of writing assignments he has to grade would discourage him from reviewing multiple drafts. Williams and others thought that Chris Kline might be invited to take on the topic “Strategies for Discouraging Cheating” in the Informal Committee on Teaching. As we prepared to adjourn, English pointed out that we had spent most of our time addressing topic 4 among those he first enumerated, and encouraged us to return next time to the other three. In that context, Finney proposed that we discuss forged signatures as another form of academic dishonesty (topic 1). With that, we adjourned at 8:52. NEXT FULL COMMITTEE MEETING: Wednesday, March 10 at 8 a.m. in LIB 134. Respectfully submitted by the ASC amanuensis, Jack Roundy