Document 12231134

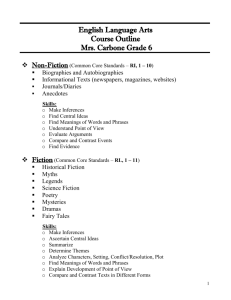

advertisement

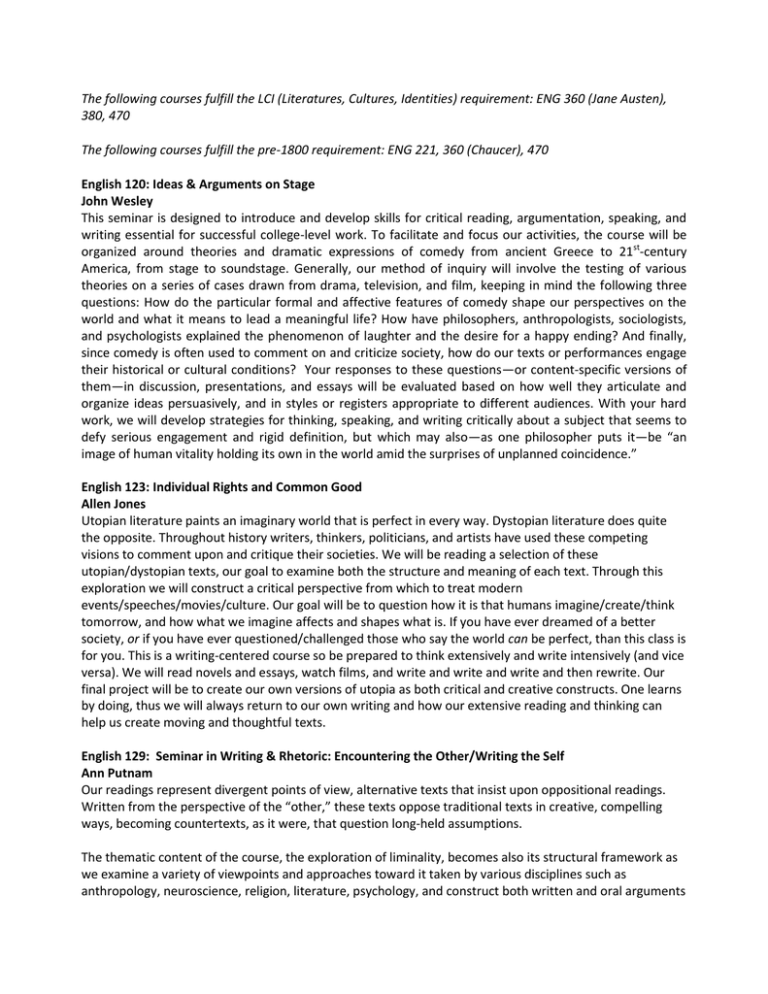

The following courses fulfill the LCI (Literatures, Cultures, Identities) requirement: ENG 360 (Jane Austen), 380, 470 The following courses fulfill the pre-1800 requirement: ENG 221, 360 (Chaucer), 470 English 120: Ideas & Arguments on Stage John Wesley This seminar is designed to introduce and develop skills for critical reading, argumentation, speaking, and writing essential for successful college-level work. To facilitate and focus our activities, the course will be organized around theories and dramatic expressions of comedy from ancient Greece to 21st-century America, from stage to soundstage. Generally, our method of inquiry will involve the testing of various theories on a series of cases drawn from drama, television, and film, keeping in mind the following three questions: How do the particular formal and affective features of comedy shape our perspectives on the world and what it means to lead a meaningful life? How have philosophers, anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists explained the phenomenon of laughter and the desire for a happy ending? And finally, since comedy is often used to comment on and criticize society, how do our texts or performances engage their historical or cultural conditions? Your responses to these questions—or content-specific versions of them—in discussion, presentations, and essays will be evaluated based on how well they articulate and organize ideas persuasively, and in styles or registers appropriate to different audiences. With your hard work, we will develop strategies for thinking, speaking, and writing critically about a subject that seems to defy serious engagement and rigid definition, but which may also—as one philosopher puts it—be “an image of human vitality holding its own in the world amid the surprises of unplanned coincidence.” English 123: Individual Rights and Common Good Allen Jones Utopian literature paints an imaginary world that is perfect in every way. Dystopian literature does quite the opposite. Throughout history writers, thinkers, politicians, and artists have used these competing visions to comment upon and critique their societies. We will be reading a selection of these utopian/dystopian texts, our goal to examine both the structure and meaning of each text. Through this exploration we will construct a critical perspective from which to treat modern events/speeches/movies/culture. Our goal will be to question how it is that humans imagine/create/think tomorrow, and how what we imagine affects and shapes what is. If you have ever dreamed of a better society, or if you have ever questioned/challenged those who say the world can be perfect, than this class is for you. This is a writing-centered course so be prepared to think extensively and write intensively (and vice versa). We will read novels and essays, watch films, and write and write and write and then rewrite. Our final project will be to create our own versions of utopia as both critical and creative constructs. One learns by doing, thus we will always return to our own writing and how our extensive reading and thinking can help us create moving and thoughtful texts. English 129: Seminar in Writing & Rhetoric: Encountering the Other/Writing the Self Ann Putnam Our readings represent divergent points of view, alternative texts that insist upon oppositional readings. Written from the perspective of the “other,” these texts oppose traditional texts in creative, compelling ways, becoming countertexts, as it were, that question long-held assumptions. The thematic content of the course, the exploration of liminality, becomes also its structural framework as we examine a variety of viewpoints and approaches toward it taken by various disciplines such as anthropology, neuroscience, religion, literature, psychology, and construct both written and oral arguments about them. The implicit if not explicit framework of the course will be the construction of persuasive arguments that examine moral, ethical and intellectual dilemmas, issues that shoot to the core of human existence. As both writers and speakers, we will construct persuasive arguments that either contradict or defend given assumptions about culture, history, identity, and the natural world. For example: American Primitive calls into question the anthropomorphism implicit in our “readings” of nature; The English Patient, the absolute borders of geography, history, and identity; bel canto: what tells us who we are when all known reference points have vanished? when the other (the enemy) becomes ourselves. It explores the in-between world where time and space are altered and identity is shattered and knit back together in new and unexpected ways. American Primitive explores the liminal world in the poet’s encounter with the natural world and the shifting sense of identity that comes out of this. The English Patient explores the complexities that make up one’s identity when inhabiting the liminal world of wartime, and the in-between place where we find a shattering of borders and boundaries in geography and personality. As we negotiate these texts we will explore ways secondary sources can enrich and deepen our understanding of the texts at hand. To that end, we will seek out sources that help guide us on our way. We will learn to find sources that speak to our most urgent concerns and to evaluate, compare and contrast those sources for their relevance and reliability. (i.e. scholarly versus popular, primary versus secondary, for example) We will also practice the use of and differences between summary, analysis, and interpretation—when and how much to use each. English 132: Writing and the Environmental Imagination William Kupinse If ecology is the relationship of living organisms to their environment, how might we describe the ecology of writer, text, and audience? How does an implicit sense of environment—whether “natural,” humanly constructed, or some combination of the two—inform written and verbal arguments? By examining a varied selection of ecological texts, this class will explore how and why writers have argued for particular understandings of the concepts of ecology and environment. Drawing on oral tradition, essays, a novel, book-length journalism, and short fiction—and with an emphasis on Northwest nature writing—we will further explore the social, political, and cultural issues at stake in these contested definitions. Among the questions this class will consider: Is wilderness a useful conceptual category for ecocritical analysis, or is it fraught with too much ideological baggage? Is wild a more productive concept for a critical practice that might inform effective resistance to current environmental degradation? How do wild and wilderness intersect with the familiar critical issues of race, gender, and colonial legacy? English 133: Not Just Fun and Games: Sport and Society in the Americas Mike Benveniste Many of us turn to sport as an escape from the pressures and concerns of everyday life, a space apart from society’s daily grind. This course, however, will explore the myriad ways that sport in enmeshed in the social world: the interplay of sports and sporting culture with socio-political conflict and ideology. Honing in on the three major sports of the Americas – baseball, soccer, and boxing – we will examine their interaction with shifting historical and social contexts in order to query the role of identity, economy, class and politics both on and off the field. Drawing on writing and film about sport, as well as sporting events themselves, students will learn the rudiments of critical analysis and argumentation, and together we will see just how permeable are the boundaries between sport and society. English 135: Travel Writing and the Other Martha Webber What kinds of travel have humans practiced over time and who has possessed the ability to travel and compose knowledge about the “Other”? From pre-industrial trade routes, the European “Grand Tour,” and contemporary “voluntourism” – what motivates travel and how does travel writing represent encounters with difference? This course will connect critical theories of travel to texts that work to construct knowledge about locations, cultures, and people – challenging texts that include 19th century missionary accounts, literary essays, poems, maps, and photographs. Over the semester, you will become adept at engaging these texts as you cultivate analytical writing and speaking skills through assignments that include academic essays and an analytical map. English 138: Seminar in Writing and Rhetoric Alison Tracy Hale This seminar in writing and rhetoric emphasizes the skills of analysis and argumentation that characterize college-level work in the liberal arts and clear thinking and expression in academic and professional fields. It is designed to give you extensive practice in discovering, supporting, revising, refining, and presenting academic arguments, in oral and written forms. In addition, the course will expose you to working with and interpreting a variety of textual and visual materials, including film, sociology, psychology, history, and urban studies. Our focus in this course is the changing face of American life—in particular, the 20th-century shift from a rural/urban population to one largely based in Suburbia—and the developments that will come in the next decades. This course will consider some of the larger historical, political, social, and demographic factors that led to our cultural disinvestment in the idea of the City as a thriving and dynamic cultural space, and those that have shaped the “Suburban America” that has characterized most of our lifetimes. We will consider the issues and events that led to “white flight,” urban poverty, the political divide, and the rise of Suburbia. We will focus our investigation on the fall and possible resurgence of the American city, from its beginnings to today. Our course will conclude with an individual research paper based on the issues most interesting to you. English 202: Introduction to Fiction Writing Ann Putnam In this course you will write two 5-6 page stories, one Short Short and one Deep Revision, in addition to keeping a writer’s log and reading lots of short stories. You will have many opportunities to participate in panels, small group workshops, large group workshops, as well as many in-class writing sessions. Each day when you come to class you will know exactly what to expect, but you will also be surprised. So you'll need to be here every day--ready to do things you've never done before, remember things you've never remembered before, ready to write about things you didn't know you knew. All you need is a brave and willing heart. English 202: Introduction to Creative Writing: Short Fiction Beverly Conner You will learn what goes into the making of short fiction, giving consideration to the process of your own creativity as well as to the techniques of theme, narrative, dialogue, description, characterization, point of view, symbol and metaphor, revision, etc. We will aim high, hoping to create literary art (not genre fiction) as we tell our tales, finding meaning for ourselves as well as offering it to our readers. Because writers of fiction read fiction (a lot!), you may find that your enthusiasm for reading stories is fueled by your development as a writer. An increased sophistication in reading imaginative literature and in developing creativity in diverse areas of life can be valuable aspects of this course for you. English 203: Introduction to Writing: Poetry Beverly Conner In this class we are attempting literary art—hoping to find meaning for ourselves and to convey it to others. You will learn about meter, rhyme, imagery, free verse, and sonnets, as well as other forms and elements of poetry. Through writing your own poems and reading a variety of poets, you will explore the genre not only as an expressive art but also as a new way of seeing: a sharper condensation of yourself and of your world. You will find that all of your writing (yes, even research papers) will be enhanced by your close attention in this class to language. English 203: Introductory Creative Writing: Poetry Hans Ostrom Combining seminar and workshop formats, the course introduces students to the art and craft of writing poetry. Students experiment with a variety of poetic forms, read the work of poets from many eras, study versification, expand their range of subjects, and explore different strategies of revision. English 211: Introduction to Creative Writing Suzanne Warren This course investigates affinities among various forms of creative writing as it introduces you to the study of three genres of literature and facilitates your creative work. Primary emphasis is on short fiction, poetry, and the personal essay. Assignments in this course emphasize writing as a process and may include readings by Flannery O'Connor, Junot Diaz, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lee Ann Roripaugh, and James Baldwin, among others; regular writing exercises; reading responses; in-class discussion; and workshops. English 220: Introduction to Literature Allen Jones We take time for granted. We set alarm clocks, make appointments, fear deadlines, and speak of time as if it exists as concretely as our experience of it. However, it is literature’s job to dig beyond the surface of things, to help us understand and explore our experience at ever-increasing depths. Thus literature cannot take time for granted. Rather, over the centuries, writers and storytellers have used time as a fundamental key to imagining and reimagining the world and our place in it. In this class we will read literature ranging from the very beginnings of human history right up to the digital revolution that at this very moment is changing the way we write and think of writing. We will examine the way these different writers use time and how this affects the possibilities of their texts. We will also examine the time period within which each writer wrote and its influence on his or her conception of time. In each segment of the course, students will be asked to think critically about our readings and to practice using time as a formal element in their own creative work. The final project will be the reinterpretation of a paper-based text as a piece of electronic literature. Students will learn how to put a piece of literature into the world of the computer program. This process will serve as the seed for original twenty-first century critical work examining the changing role of time as a structural and thematic element in literature. English 221: British Literature I – Medieval to Renaissance John Wesley This course will introduce you to some of the major works of literature written in Britain from the AngloSaxon invasion to the aftermath of the English Civil War. Along the way, you will also be introduced to a number of different genres and forms, as well as to many of the key terms and concepts that help us think critically about texts. Although the stories are diverse, and range over some nine or ten centuries, our discussions throughout the term will revolve (though not exclusively) around the relationship between literature and religion, especially in terms of its impact on heroic ideals, concepts of family and nation, the meaning of devotion, the understanding of the cosmos, or the apocalyptic imagination. In order to better appreciate how literature expresses and re-interprets these ideas over such a vast stretch of time, we will study the survey period three times in three ways; that is, rather than reading once straight through the centuries, this course focuses on three different generic clusters—1) heroic narrative, 2) drama, and 3) confession and lyric—all under the broad rubric of “Faith, Reason, and the Imagination.” Thus, while learning techniques and vocabulary for close textual analysis, we will also gain a wider contextual framework by touching on the cultural transformations of Britain from the Christianization of its early Germanic invaders to the religious and political revolutions of the seventeenth century, noting especially the religious upheaval of the sixteenth century known as the English Reformation, when Britain turned officially from Catholicism to Protestantism in a matter of only a few decades. Readings include selections from Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, The Canterbury Tales, The Faerie Queene, Doctor Faustus, The Duchess of Malfi, and Paradise Lost, as well as shorter lyric poems and confessional literature. English 226: Survey of Literature by Women Ann Putnam After setting up some initial terms and contexts, we will follow a chronology which traces the development of the female literary tradition from the Medieval and Renaissance Periods up to the present. We will place each work in its historical, cultural and literary context. Sometimes we’ll read works which seem to speak to each other from across the expanse of decades or even centuries, though chronology will be the main way we’ll organize our readings. Several of the issues we’ll address include: (1) What are the canonical issues which come from a study of women’s literature? what issues emerge concerning the idea of the canon in general and the Norton Text in particular? Why has it come under such criticism? Why is there no Norton Anthology of Literature by Men? What works have been discovered or reclaimed? What happens to a developing literary tradition when key works have been lost or devalued? For this we will examine both “The Awakening” and “Life in the Iron Mills,” to name two. (2) Are there significant differences in women’s literature which we can characterize? Is women’s literature different from literature by men in some essential way? If so how? We will begin by looking at Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. (3) How have women been characterized through the ages in works written by men? Why have such concepts or images as the gaze, the mirror, silences, the blank page, a room of one’s own, the monster, the madwoman in the attic become gathering metaphors we encounter again and again in literature by women? (4) What has it been like through the ages to be both a woman and an artist? What has it cost women to follow their creative urgings? Why have they agonized over this? And why have they so often thought of their writing as something monstrous, perverted, abnormal, something to be hidden and composed anonymously and in private? What obstacles have women writers faced throughout history? What forces work against them and what strategies do they often employ to make their voices heard? How have women found the voice to write? What has changed? What has remained the same? We will examine what Emily Dickinson meant when she said, “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” by looking at the strategies women writers have employed through the ages. We will contrast the strategies of outright rebellion; disguises and masks; apology and deference; and transposition. English 236: Literature and the Quest for Personal Identity Michael J. Curley The aim of this course is to introduce you to the rich literature devoted to the theme of the individual's search for personal identity. We all strive to identify ourselves in relation to family, religion, nationality, social status, work, gender, race, language, tradition, authority, and so on. Yet to understand this familiar struggle for identity in the life of a Greek woman, a nineteenth-century Russian student or an Italian Jewish prisoner in Auschwitz requires the exercise of our intellectual and imaginative powers. In order to give form to our reading, English 236 will be organized loosely around three topics: Family, Love and Freedom. We shall quickly appreciate how interrelated our three topics are, and how uncertain are the lines that separate one from the other. I hope that this course will play an important role in your lifelong education, and that it will encourage you to read at some time in the future another Russian novel, another Greek play, another Irish writer, that it will build your confidence, fire your imagination, illuminate your intellect and capture your heart. English 301 Intermediate Composition: Eureka! Narratives of Scientific Discovery Martha Webber “We can publish” Aaron says to his friend and research partner, Abe, about their invention in the 2004 film Primer. “Yeah, we can publish,” Abe responds. What ensues when these two researchers decide not to publish the results of their time-travel experiment offers a compelling narrative for viewers, but also raises ethical questions about the impact of scientific research that remains unpublished or unknown to the public. For this course we will read and view accounts of scientific discoveries to examine them in terms of their narrative elements. How do narrative features (such as point of view, complication, and resolution) create scientific understanding and for what audiences are they composed? Major assignments include two analytical essays, a “story map” where you will create narrative meaning with words and images, and an academic personal statement that incorporates narrative elements to communicate your experience and qualifications for entrance into graduate or professional school. Texts include the film Primer, James Watson’s The Double Helix, Lauren Redniss’ illustrated biography, Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout, as well as selections from the Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory and other narrative theorists. English 306: Playwriting Hans Ostrom The course will introduce students to the art and craft of playwriting and builds on what students have learned writing in other creative genres or in playwriting already. English/Theatre 306 combines seminar and workshop formats in which we write, present, and revise monologues, dialogues, and sketches. We will work toward a final portfolio of this material as well as the completion of a short one-act play. The course will also involve the analysis and discussion of published, produced plays; of conflict, suspense, characterization, plot, and other elements of drama; and of writing with actors, directors, producers, dramaturges, and theatre audiences in mind. We will also explore collaborative modes of creation. Crosslisted as THTR 306. English 343: Literary Genre: Personal Essay Suzanne Warren The essay is a capacious form, drawing on many of the resources of fiction—character, plot, point of view— yet also inviting direct “telling” by the narrator. According to the great anthologist of the form, Phillip Lopate, the essay is a “mode of thinking and being” marked by intimacy, a conversational quality, and contrariety; a tendency toward cheek and irony; and a preference for the past, the local, and the melancholic. In this class, we will *essay* these questions: what makes an essay an essay? How have its rhetorical functions changed over time? What do we owe our subjects and audiences in the way of truthtelling? How can we adapt the personal essay to tell our own stories? Course texts include Phillip Lopate’s The Art of the Personal Essay and Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and the Story. Essayists may include Sei Shonagon, Michel de Montaigne, St. Augustine, Virginia Woolf, George Orwell, E. B. White, Annie Dillard, Richard Rodriguez, James Baldwin, Sara Suleri, Alice Walker, and David Shields. English 360: Chaucer Denise Despres When Geoffrey Chaucer began his career around 1370 as a court poet, French was the language in which to explore sentiment, Latin the vehicle for learned subjects. Chaucer’s commitment to English in view of the scope and breadth of his literary ambition thus reflects a creative adventurousness that justly earned him the reputation as the father of English poetry. His legacy to the fifteenth-century poets was an enriched language with the metrical versatility requisite for grand creations in the tradition of Virgil and Ovid, those literary predecessors most admired and imitated by medieval writers. Modern readers, influenced by eighteenth and nineteenth-century literary critics, view Chaucer largely as a comic realist, a precursor of Shakespeare and the author primarily of The Canterbury Tales. This course will focus on his transformation from a sophisticated courtly love poet to the philosophical craftsman of his greatest work, most admired by medieval readers: Troilus and Criseyde. The evolution of themes, imagery, and ethical issues central Chaucer’s poetic ethic will occupy the early part of the course, when we focus on his indebtedness to the influential medieval works (the Consolation of Philosophy and the Romance of the Rose) he translated and mined in his dream visions and Troilus and Criseyde. This material will enable us to be critical readers of The Canterbury Tales, where Chaucer engages most consistently the value and purpose of poetry in a Christian moral universe, rethinking—as poets did throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Plato’s assertion that poetry is untruthful and that poets must be banished from the moral Republic. English 360: Jane Austen Mita Mahato This course takes as its focus the novels of Jane Austen (1775-1817) and the social, political, literary, and domestic contexts that influence her craft. While recent cinematic and literary adaptations have promulgated the idea that Austen’s novels are trite and easily digestible romances, her “home-bound” perspective on issues including marriage, dandyism, colonialism, healthcare, and class showcase an intricate discursive exchange between domestic and political spheres that demands engaged and nuanced reading. This exchange and its varied manifestations throughout Austen’s major novels will be the star of this course; by studying how Austen articulates ambivalent movements between the domestic and political—between inside and outside, female and male, England and other, writing and reading—students will identify and appreciate the unique and groundbreaking narratives stylings that have made Austen into a cultural and literary touchstone. In addition to works by Austen, readings will include short contemporaneous texts as well as recent scholarly criticism. This course is cross-listed with Gender Studies and fulfills the LCI requirement for majors. English 380: Literature and Environment William Kupinse ENGL 380 will explore the development of environmental writing in English-language texts with an emphasis on twentieth-century fiction, poetry, and memoir. Covering a wide range of geographical settings and literary genres, we will examine each text as an argument for a particular “reading” of the environment, and we will further inquire about real-world consequences of that reading. Our investigation will address questions of both historical and topical importance: How pervasive is the Romantic vision of nature today? How have the legacies of war and colonialism affected not only the environment but our understanding and use of it? What does environmental literature have to add to current scholarship on race, class, and gender? Finally, in an era that has diagnosed "the trouble with Wilderness" and proclaimed "the end of Nature" (to allude to the respective titles of paradigm-shattering works by William Cronon and Bill McKibben), what contributions can emerging ecocritical models--of "dark" ecology, "ecology without nature," or "bodily natures"--offer, as both aesthetic and ethical interventions? In addition to regular participation, this course will require three short and one long written assignments, a group presentation, and a final exam. English 402: Advanced Creative Writing: Fiction Suzanne Warren In this course, you will deepen their ability to write and revise short stories. You are expected to have a firm grasp of the basic elements of fiction—plot, character, structure, point of view, timeline, setting, and tone—and a nascent understanding of your writerly identity. You may have begun to think about what role your fiction might play in shaping our understanding of the world. With that in mind, more of the responsibility for the success of the class is shifted onto you, the student. We workshop near-weekly and read, write, and revise heavily. We adopt four literary journals as class texts, which students present to the class as a panel. At the same time, the lessons of Fiction 101 bear repeating in this class: reading makes writers; participation in workshop benefits the reader as much as the writer; the art of revision distinguishes the advanced writer from the beginner. English 403: Advanced Poetry Writing William Kupinse “A line will take us hours, maybe,” writes W. B. Yeats on the craft of poetry. “Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought, / Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.” This creative writing workshop will take seriously Yeats’s notion that the effect of spontaneity in poetry is achieved only through fierce attention and substantial effort. By stitching and unstitching multiple drafts of their poems, seminar participants will work to develop the critical skills that will allow them to become more effective writers of poetry. Assignments in this course will emphasize writing as a process and will include selected reading of canonical and contemporary poems, weekly exercises, mid-term and final self-assessment essays and portfolios, in-class discussions, and peer reviews. An on-campus reading of student work will be held at the end of the term. English 405: Writing and Gender Martha Webber Can writing be gendered or sentences sexed? Are there experiences – such as combat, pregnancy, or even wearing clothing – that only men or only women may write about? Moreover, how have literary and popular readerships accorded value to texts about these experiences? Our seminar begins by reading theories of gender that work to understand it as a complex interplay of biological and cultural influences (including Fausto-Sterling’s Sexing the Body and Fine’s Delusions of Gender). From there we will consider theories of women and men’s writing as we apply them to literary and everyday texts – including texts that you will research and present about to the class. Our seminar will examine accounts of warfare, motherhood, and wearing clothing – significantly gendered experiences – to understand how texts work to represent these experiences to readers. We will question how these accounts both affirm and challenge conventional representations of gender, from Jarhead to the “Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong” and from Navel Gazing to a “Bloodchild.” English 442: Seventeenth-Century Literature: Deceit and Dissent John Wesley We will study the poetry, prose, and drama written in England between the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603 and the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. These politically tumultuous years, which witnessed the outbreak of the Civil Wars, also produced some of the most innovative works in English literature. We will examine how literature of the Jacobean and Caroline periods manifests deceit and dissent on both thematic and structural levels. Lectures and discussions will focus on close textual analysis of selected texts by Francis Bacon, Ben Jonson, Aemilia Lanyer, John Donne, Mary Wroth, George Herbert, Richard Crashaw, Henry Vaughan, John Webster, Elizabeth Cary, Thomas Hobbes, Margaret Cavendish, John Milton, Katherine Philips, Robert Herrick, Lucy Hutchinson, and Andrew Marvell. The course will explore how these writers engaged in seventeenth-century debates concerning personal and political sovereignty, censorship, gender, religion, social hierarchy, courtship and marriage, nationhood, race, and women’s authorship. We will also consider how literature of this period both appropriates and challenges established generic, structural, and stylistic conventions. English 458: US Fiction after 1945: Race, Realism and Cold War Culture Mike Benveniste By most accounts, US culture, and hence literature, underwent a massive paradigm shift which challenged the very notion of reality in the years after WWII. Doubtless, in this period – formerly known as the Postmodern – historical factors like the Cold war, the Civil Rights Movement, identity politics, postindustrialism, accelerated technological transformation and the ‘end of ideology’ altered the way that writers and intellectuals understood their social reality, and influenced their response to it. Empirically speaking, one of the defining features of this era is the historically unprecedented diversity of its novelists. In this course, we will study a multi-ethnic canon of writers from 1945 to the present in order to think about literature as a tactical response to its social conflict, with a particular focus on the ways that ethnic writers in the post-war period have used the novel to address inequality. Spanning novels from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man to Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, we will see that the novel, while certainly mediated by the structures and ideologies of its historical moment, can also be a site of innovation as it confronts new problems. Because this period is paradoxically marked both by Postmodernism’s rejection of realism and ethnic literature’s reinvestment in the socio-political, we will place these writers alongside Postmodern stalwarts like DonDelillo or Thomas Pynchon, to pursue the slippery question of what realism might mean in contemporary literature. Other novelists may include Karen Tei Yamashita, Colson Whitehead, Salvador Plascencia, John Rechy, Ishmael Reed, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, E.L. Doctorow, Mohsin Hamid, Richard Powers, Bharati Mukherjee and Jonathan Safran Foer. English 470: Gothic America Alison Tracy Hale As no less a figure than novelist Toni Morrison has noted, “it is striking how dour, how troubled, how frightened and haunted our early and founding literature truly is” (Playing in the Dark, 1992). A course in the American Gothic, by definition, inhabits the dark side of American identity, society, and history. Familiar narratives about the U.S. suggest strongly that our national identity is based on progress, reason, and optimism; the literature you will read in this course undermines that narrative, reinscribing the American "dream" as an American "nightmare." Long considered trivial and "non-literary," the gothic genre was once derided as an escapist form of sensational fiction unworthy of critical attention. Recent work, however, has challenged such an easy distinction between America’s progressive mythology and its gothic undercurrents, and this course will be devoted to investigating gothic texts as central to the expression, articulation, repression, and management of significant tensions in American culture at the collective and individual levels. Over the semester, we will explore the very idea of an American gothic: how is a genre associated with the haunted castles, demonic noblemen, and ancient mysteries of Europe re-envisioned in particularly "American" ways? How do American authors and texts re-imagine gothic tropes and images in order to convey uniquely American anxieties? When and how does the genre allow for subversive approaches to pressing questions, and in what circumstances might it perhaps reinforce the status quo? Readings will likely include works by Charles Brockden Brown, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Stephen Crane, Shirley Jackson, Flannery O’Connor, Truman Capote, William Faulkner, and Colson Whitehead. Requirements: two substantial literary analysis essays, shorter assignments, and the presentation of a critical/secondary source. Prerequisites: English 210; English 224 or 225. English 471: Special Topics in Writing, Rhetoric and Culture: The Rhetoric of Literacy Julie Nelson Christoph The Oxford English Dictionary, known for its compendious definitions of words in the English language, defines “literacy” quite simply as “The quality or state of being literate; knowledge of letters; condition in respect to education, esp. ability to read and write. Also transf.” While this entry provides a good definition of what literacy itself is, the cultural meaning and import of literacy is much more complex. Literate in what, or whose language? How much knowledge of letters? In respect to what kind of education? Ability to read and write what? Transferred sense to what? This seemingly simple definition has complex implications for individuals and cultures, and many of the major political and social issues of our time—such as questions about nationhood, education, and social services—are intertwined with literacy concerns. In the Spring 2013 Special Topics in Writing, Rhetoric, and Culture, students will consider the role of rhetoric in constructing notions of literacy and will be engaging in discussions about theoretical and critical readings from the New Literacy Studies, ethnographic and narrative accounts of literacy practices within specific cultures, and debates about literacy in the popular press. English 497: The Writing Internship Mita Mahato The Writing Internship combines internship work with traditional coursework, giving students the unique opportunity to begin their transition from college to the sometimes daunting world “out there.” In bringing together experience and reflection—work and school—students enrolled in this course practice and reflect upon the professional writing they might encounter after graduation from Puget Sound. Past students have completed a wide range of work in their internships, including copy editing and layout for publishers of children's books, editing for local and national magazines, and public relations writing for local businesses or not-for-profit organizations. In the classroom portion of the course (we will have weekly meetings), students consider the relationship between coursework and work by studying their experiences as interns through the lenses of voice, style, and context. Although the course is not designed to be a “how-to” on technical and professional writing, students become skilled in several writing genres by completing assigned readings, participating in discussions, workshopping writing, and presenting work-related issues to each other. In addition, the course provides students with a forum in which to trouble-shoot difficulties in their internships when they arise, explore career goals, consider ethical and practical concerns, make valuable connections, and gain relevant and useful skills and experiences. By the end of the semester, all enrolled students should have solid templates of their cover letters and résumés, as well as practical know-how that will help them take on the post-graduate job market. All interested students should speak with Mita Mahato immediately to begin the process of locating and securing an appropriate internship to coincide with the Spring semester. Connections 303: The Monstrous Middle Ages Denise Despres and David Tinsley Today, we naturally “connect” the medieval period with monstrosity, and rightly so. While popular culture has relegated the monstrous to subgenres of film and literature, medieval culture embraced monstrosity and all its ambiguity as the border between human ingenuity and Platonic form, culture and the darker forces of fallen nature, self and the ever-present other (Saracen, Jew, Mongol, Hermaphrodite, to name a few). Humanities 303 explores medieval ontology, the nature of creation and our human ability to know it fully, through the monstrous. Recent research in art history, geography, anthropology, literary history, and cultural studies enables medievalists to offer undergraduates current scholarship in an interdisciplinary format; as cultural historians whose published scholarship ranges from the disciplines of art history to literary and religious studies, we welcome the opportunity to collaborate with you in search of an answer to Bernard’s haunting question: Why does monstrosity assume such a visible place in medieval culture? In turn, we hope that you will emerge with a critical methodology for cultural studies in other periods. You will not be surprised to discover that Renaissance historiographers, sharing the classical heritage with medieval intellectuals, were equally fascinated with monstrosity and compiled their own “scientific” works on the marvelous.