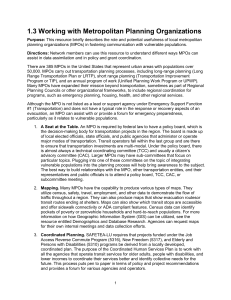

Small MPO Funding

advertisement