HORSE HEALTH LINES

advertisement

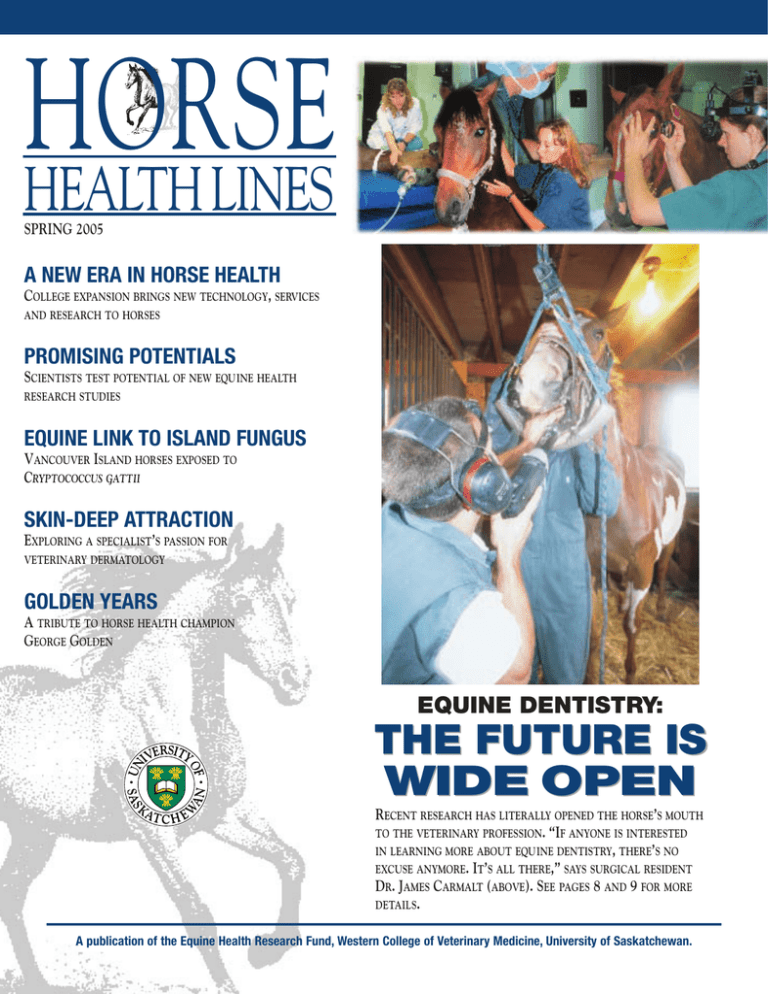

HORSE HEALTH LINES SPRING 2005 A NEW ERA IN HORSE HEALTH COLLEGE EXPANSION BRINGS NEW TECHNOLOGY, SERVICES AND RESEARCH TO HORSES PROMISING POTENTIALS SCIENTISTS TEST POTENTIAL OF NEW EQUINE HEALTH RESEARCH STUDIES EQUINE LINK TO ISLAND FUNGUS VANCOUVER ISLAND HORSES EXPOSED TO CRYPTOCOCCUS GATTII SKIN-DEEP ATTRACTION EXPLORING A SPECIALIST’S PASSION FOR VETERINARY DERMATOLOGY GOLDEN YEARS A TRIBUTE TO HORSE HEALTH CHAMPION GEORGE GOLDEN EQUINE DENTISTRY: THE FUTURE IS WIDE OPEN RECENT RESEARCH HAS LITERALLY OPENED THE HORSE’S MOUTH TO THE VETERINARY PROFESSION. “IF ANYONE IS INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE ABOUT EQUINE DENTISTRY, THERE’S NO EXCUSE ANYMORE. IT’S ALL THERE,” SAYS SURGICAL RESIDENT DR. JAMES CARMALT (ABOVE). SEE PAGES 8 AND 9 FOR MORE DETAILS. A publication of the Equine Health Research Fund, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Saskatchewan. A New Era in HORSE H E A LT H W ith the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s $43-million transformation now underway, bringing horses to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital calls for dexterity in the parking lot. “We’re starting to deal with some traffic challenges in our animal receiving area,” says Dr. David Wilson, head of WCVM’s Large Animal Clinical Sciences department. “As larger equipment moves in, clients may have to wait before unloading their animals.” But as Wilson points out, these traffic challenges won’t affect the quality of clinical services. And in the long run, any short-term disruptions are well worth the benefits that all western Canadians — including horse enthusiasts — will gain once the College completes the major expansion and upgrade of its facilities in 2008. To reach that point, construction crews will add more than 11,000 square metres to the College’s original 25,290-square-metre building and renovate nearly 6,900 square metres of existing facilities during the next three years. Plans involve more than two dozen “sub-projects” including a two-storey addition to the veterinary teaching hospital, a food animal clinical teaching facility, consolidated research animal housing, “multi-use” research laboratories and an upgraded diagnostic services area. “Mixed into that, we’re planning construction in phases since our teaching, research, clinics and diagnostic laboratories must continue operating throughout the project,” explains WCVM Dean Dr. Charles Rhodes. He adds that the federal government has already provided $22.2 million in funding for the project, and the Saskatchewan government committed $15 million in November 2004. WCVM will raise the final $5 million through its Veterinary Teaching Hospital capital campaign. While three years of construction is posing logistical challenges, hospital director Dr. Stan Rubin confirms that it’s “business as usual.” Regular services will continue even during major renovations to the hospital’s surgical, examination and animal care facilities in its Small Animal and Large Animal Clinics. The key is planning construction in phases so regular hospital services continue operating, explains Rubin, a member of the College’s hospital expansion committee. The committee, which is chaired by WCVM veterinary ophthalmologist Dr. Bruce Grahn, is one of the College’s four planning teams. Directed by Rhodes, all of the committees have been working closely with the project architect (AODBT), the project manager (UMA Engineering) and the construction manager (Graham Construction) to plan the College’s renovations in phases. 2 Horse Health Lines • Spring 2005 Construction crews will add more than 11,000 square metres to the College’s original 25,290-square-metre building and renovate nearly 6,900 square metres of existing facilities during the next three years. For WCVM’s large animal clients, noticeable changes include: • a safer chute complex in the large animal handling area and an expanded “stocks” area to accommodate additional equine patients. • a modernized surgical “core area” with more spacious suites for large animal surgery. Renovated facilities include a surgery room dedicated to performing surgery in standing, sedated cows. • improved biosecurity throughout the Veterinary Teaching Hospital and improvements to isolation facilities to reduce the spread of infection. Above: Equine surgical specialists will have more room to work in the Large Animal Clinic’s renovated surgical suites. At right: This architect’s rendering shows the Veterinary Teaching Hospital’s two-storey addition, the remodelled Large Animal Clinic entrance and additional garage space for the hospital’s ambulatory service. Extensive renovations will allow staff to shut down a particular ward from the rest of the hospital in case of a biosecurity issue. Traffic patterns will be altered between equine and bovine wards so humans and animals can’t walk directly between wards. Remodelled wards will also have stalls equipped with flooring materials that can be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Although most of the isolation units are already on the building’s periphery, Wilson says the expansion project will provide additional space for calf isolation and a separate anteroom for each isolation unit. Health care workers can use these rooms to dress and remove special protective clothing before returning to the hospital. • a renovated large animal reception, a new field service office and storage room, and some client consultation rooms. Construction crews will also build additional garage space for the Veterinary Teaching Hospital’s ambulatory service. With final approvals from the University of Saskatchewan and Environment Canada in place, construction workers moved on site in October 2004. As Rhodes explains, the crews are using a staggered, “construction management process” that allows planning to continue on one area of the project while construction is fully underway on another area. “It’s more time efficient, it’s easier to stay on budget, and if we have late-stage changes, it’s more flexible than the traditional, single-tender approach.” Just as construction plans need to be flexible in the next three years, the College’s staff, clinicians and students are quickly learning to adapt to a variety of environments, situations and new roles — such as the temporary job of traffic cop in the clinic’s parking lot. “These problems are surmountable, and it’s going to be more of a temporary inconvenience than anything,” assures Wilson. “And when everything is finished, we’ll definitely be competitive with any veterinary teaching, research and clinical facility in North America.” Visit www.wcvm.com to learn about the College’s expansion project. From the Dean’s Desk This issue of Horse Health Lines includes a tribute to George Golden — an Alberta horseman who recognized the long-term value of supporting equine health research and training at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine. Besides helping to establish the Equine Health Research Fund, George was one of WCVM’s earliest advocates in the horse industry. More than three decades after George made his first contribution to WCVM, thousands of horse owners and veterinarians continue to follow his example. That grassroots support has enabled our faculty and graduate students to forge ahead in many aspects of horse health research. It has also allowed WCVM to generate a network of equine specialists who continue to improve health care for horses around the world. Now, the College’s $43-million expansion will provide WCVM’s equine research and training programs with the facilities and resources they need to produce even more research, more specialists and more services for horse owners. New laboratories will provide our students, faculty and staff with the facilities and tools they need to conduct advanced research. An expanded Veterinary Teaching Hospital will also increase the number of specialized services we offer to horse owners and referring veterinarians. In turn, this will provide students with a larger and more diverse caseload that enriches their education and provides them with solid experience they can take into the field. As we grow, so will the Fund — and that’s why it’s important for you to continue your support of the College’s horse health programs. I’m also asking you to consider making a special contribution to our Veterinary Teaching Hospital capital campaign. While the federal government and the province of Saskatchewan have committed more than $37 million to the entire expansion, we must raise the final $5 million from WCVM’s alumni, friends and stakeholders before we can complete this project. We can accomplish several goals with your support. By expanding WCVM, we can strengthen the College’s role as Western Canada’s centre for veterinary education, research and expertise. We can continue being an integral part of national networks for animal and public health. And we can provide our partners — including the Equine Health Research Fund — with the facilities and resources needed to enhance WCVM’s animal health research and training programs. Ultimately, this expansion project will significantly increase the Equine Health Research Fund’s potential for improving the quality of horse health care — a goal that George Golden and the rest of the Fund’s founders envisioned nearly 30 years ago. These are exciting times for the College, and we look forward to having you join in our plans for expanding your world of veterinary medicine. You can help by continuing your support of the Equine Health Research Fund — and by considering a special contribution to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital capital campaign this year. You’ll find all of the information you need to make both donations on the enclosed tear out cards or visit www.wcvm.com/supportus. If you have any questions about EHRF or the VTH capital campaign, please contact Joanne Wurmlinger, WCVM’s development officer, at 306966-7450 (joanne.wurmlinger@usask.ca). Enjoy the rest of Horse Health Lines — and thank you for investing in the future of veterinary medicine. Dr. Charles Rhodes, Dean, WCVM Promising POTENTIALS PROMISING (adj.): likely to be successful or to turn out well. POTENTIAL (noun): the capacity or ability for future development or achievement. These two words are a fitting description for the 200506 lineup of research projects supported by the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s Equine Health Research Fund. Worth just over $93,000, discoveries stemming from these five promising studies have the potential to save millions of dollars in health costs for horse owners around the world. Can lidocaine prevent intestinal damage after colic surgery? Drs. Ryan Shoemaker, David Wilson, Andy Allen and Jenny Kelly Horses that undergo surgery for small intestine-related colic have a low survival rate. Many suffer postoperative complications like ileus (lack of movement in the intestine), abdominal adhesions or systemic illness. The culprit? Overzealous neutrophils. These primary white blood cells infiltrate the small intestine and potentially cause post-surgery complications to develop. Scientists have proven that intravenous lidocaine (a local anesthetic) decreases the migration and adverse actions of neutrophils on tissue in humans and other species. In the next 14 months, two teams of WCVM surgical specialists will simultaneously perform experimental surgical procedures on pairs of anesthetized horses (nine pairs altogether). Their goal is to mimic naturally occurring small intestine strangulation and bowel distention in experimental models. Once the teams have recreated this scenario, each horse will receive intravenous infusions of lidocaine or saline solution for the remainder of the experiment. If tissue samples show that continuous lidocaine infusions during surgery reduce neutrophil accumulation and activation in patients’ small intestines, surgical specialists will gain a new tool in preventing complications after colic surgery. Bone Scans Reduce GUESSWORK As part of its expansion plans, WCVM will bring one of the most useful tools for diagnosing difficult equine lameness cases to its Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Nuclear scintigraphy — or bone scanning — detects increased bone turnover (or bone remodelling) that’s associated with stress fractures, arthritis, bone injuries and infections. “If you take 100 lame horses, we can usually sort out the problems in 80 of those cases. The remaining 20 per cent will be horses with unidentifiable lamenesses,” explains equine surgical specialist Dr. David Wilson. “But with nuclear scintigraphy, we can make a definitive diagnosis in about 18 of those 20 tough cases. Having the technology will increase our success rate in correctly diagnosing equine lameness.” Can we treat heaves by removing pro-inflammatory cells? Drs. Baljit Singh and Hugh Townsend Recurrent airway disease (heaves) is a chronic respiratory disease that impairs lung function and compromises performance in mature horses. Besides reducing a horse’s exposure to allergens, bronchodilators and corticosteroids can help to treat the disease symptoms — but long-term corticosteroid use isn’t recommended. As an alternative, Drs. Baljit Singh and Hugh Townsend will test the potential for “knocking out” pulmonary intravascular macrophages (PIMs) — pro-inflammatory cells that may play a central role in heaves development. Previous studies have shown that depleting a body’s supply of these inflammatory molecules will neutralize endotoxin-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension and lung inflammation. To test the potential role of PIMs in heaves, the research team will assemble five normal horses and another five horses diagnosed with heaves. Both groups will then undergo a PIM-depleting protocol. Researchers will use bronchoalveolar lavages and lung biopsies to examine lung responses of all horses before and after the process. They’ll also conduct clinical examinations of all horses while they’re kept in a clean environment for one month. After 30 days, the research team will move all of the horses to a heavesprovoking environment, then take further lung samples. If horses diagnosed EHRF-supported research includes a study looking at whether R. equi-susceptible foals have impaired immunity (above), a surgical trial to test drug therapy that may prevent complications after colic surgery (right, top) and an in-depth investigation of congenital stationary night blindness in Appaloosa horses (right, centre). Besides horses, WCVM’s newest diagnostic technology will be used on other large animals and small animal patients. The College will purchase the specialized equipment once renovations are completed in the areas that will house nuclear scintigraphy and the CT (computed tomography) scanner — another diagnostic tool that WCVM installed in 2004. During a bone scan, a medical imaging specialist injects a radioisotope (a radioactive compound called Technetium 99 combined with MDP, a bone seeking agent) into a horse’s vein. After circulating through the bloodstream, the radiopharmaceutical concentrates in the bone — especially where there’s increased metabolic activity. When the horse stands in front of a gamma camera, the device shoots signals back to a computer, and it develops a scintigram highlighting “hot spots” of increased bone remodelling. Veterinarians regularly use nuclear scintigraphy to diagnose difficult lameness problems like incomplete fractures of the cannon bone, damage to the high suspensory ligament and low-grade arthritis. More with heaves show inhibition of inflammation following exposure to allergens, this project may lay the foundation for developing a new treatment method for heaves. Can genetics help identify high-risk patients for endotoxemia? Dr. Katharina Lohmann Endotoxemia (endotoxin in the bloodstream) is a life-threatening complication of many common equine diseases including colic, endometritis (inflammation of the uterus) and pleuropneumonia. While the ability to mount an inflammatory response to endotoxin is part of the body’s natural defense against infection, overwhelming amounts can stimulate a systemic (generalized) inflammatory reaction that may result in complications like laminitis, a permanent loss of athletic ability or even death. Based on studies in humans and other species, it’s possible that gene sequence variations among individual horses — as detected by the identification of certain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) — may be associated with differences in the immune response to endotoxin. As a result, finding these SNPs may help identify horses that have an increased susceptibility to the effects of endotoxemia. While no one has characterized the genetic factors influencing the response to endotoxin in horses, Dr. Katharina Lohmann has identified SNP in equine genes encoding innate immune sensors like Toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) and MD-2, as well as in inflammatory mediators such as equine tumour necrosis factor a (TNFa). This year, Lohmann plans to build on these preliminary findings. Using a large group of 50 horses, the scientist will evaluate the animals’ gene sequences to estimate the prevalence of SNP in the equine population and investigate their association with endotoxin-induced TNFa production in vitro. This study will be the first step toward characterizing genetic risk factors for endotoxemia in horses, and ultimately, could allow clinicians to use preventive therapy on high-risk patients. It may also lead to individualized therapy, more accurate prognoses and more informed breeding strategies for the horse industry. recently, it’s been used to identify incomplete pelvic fractures, navicular disease, abnormal teeth and for measuring the speed of transport through the gastrointestinal tract. Nuclear scintigraphy usually isn’t the first diagnostic tool that equine specialists use, but if all other imaging methods fail, a bone scan can refocus the diagnostic process. “For example, once a hot spot is identified over a tooth, that stimulates people to reexamine a radiograph or to take another X-ray. In our case at WCVM, we may even decide to perform a CT scan to get a better idea of what’s going on,” explains Wilson. In the past, western Canadian horse owners travelled to the University of Minnesota or Washington State University to access nuclear scintigraphy. The technology is now available at Moore & Company, an equine veterinary clinic north of Calgary, Alta., and accessibility will be even better once WCVM offers the diagnostic service: “We see lots of cases where it would help to make a definitive diagnosis. Once we have the technology in place, this will be the next step in most of those undiagnosed cases,” says Wilson. Is CSNB linked to the gene responsible for leopard Appaloosas? Drs. Lynne Sandmeyer, Bruce Grahn and Carrie Breaux Congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB) is a hereditary condition in Appaloosa horses. Affected animals can have visual problems ranging from reduced vision to complete blindness in dim light, or even reduced vision in normal light. While the disease’s inheritance pattern is still unknown, reports from breeders suggest that clinical signs of CSNB are more common in Appaloosas with the homozygous leopard complex (Lp) or leopard coat patterns. Geneticists recently mapped Lp to a small region on equine chromosome 1. One potential candidate gene for Lp is the pink eyed dilution gene that’s responsible for oculocutaneous albinism in humans — an hereditary disorder characterized by a deficiency of the pigment melanin in the eyes, skin and hair. Affected people have structural abnormalities of the optic nerves and optic tracts of the brain. Scientists hypothesize that similar abnormalities cause CSNB in Appaloosas. During the next two years, veterinary ophthalmologists will conduct an in-depth investigation of the clinical, electroretinography and structural characteristics of CSNB in Appaloosas. As well, the research team hopes to confirm the disease’s inheritance pattern. If their findings confirm that CSNB is linked to the gene responsible for leopard coat patterns, then future investigations will focus on finding the gene responsible for CSNB in the breed. This information could also lead to the eventual development of gene therapy for this condition. Do R. equi-susceptible foals have low expression levels of antimicrobial peptides? Drs. Hugh Townsend, Marianela Lopez, Volker Gerdts and Sam Attah-Poku Rhodococcus equi is a soil-borne, Gram-positive bacterium that causes rhodococcal pneumonia in young foals. The bacteria concerns horse breeders since prevalence and case fatality rates are high on endemic farms. As well, available therapies are expensive and not always effective. Scientists still don’t know why young foals are more susceptible to R. equi, but evidence supports the theory that immaturity of the immune system in neonates is responsible for this susceptibility. As part of the innate immune system, antimicrobial peptides are molecules capable of eliminating a broad spectrum of bacteria, fungi and parasites. Major components of this peptide-base defense system — ß-defensins and cathelicidins — have been identified in the horse, and they have shown antimicrobial properties in vitro. During the next year, a team of researchers at WCVM and at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization will determine whether these molecules are able to eliminate R. equi. The team will also investigate whether low expression levels of these antimicrobial peptides in the mucosal surfaces are associated with the foals’ susceptibility to R. equi infection. By gaining a better understanding of the immunologic mechanisms associated with the increased susceptibility of individual foals to R. equi infection, scientists can develop more effective ways to control and prevent this devastating disease. Western College of Veterinary Medicine 5 I n October 2003, Dr. Colleen Duncan of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine had just finished a summer-long investigation into the spread of cryptococcosis among cats and dogs on Vancouver Island. After concentrating on small animals for most of the year, the graduate student was putting the final touches on a new research proposal that targeted another potential victim of the rare fungal disease: the thousands of horses living on the Island. Then she heard the news: for the first time, diagnostic bacteriologists had isolated Cryptococcus gattii — the same fungus that had caused cryptococcal disease in hundreds of pets, wild animals and humans — from an Island horse with pneumonia. “It made us ask the question: if we look hard enough, will we find the cryptococcal infection in more horses?” says Duncan, who helped to perform the post mortem examination on the Cryptococcusinfected horse. The case also became part of the successful Equine Health Research Fund proposal that she and her graduate studies supervisors — Dr. John Campbell of WCVM and Dr. Craig Stephen of the Centre for Coastal Health in Nanaimo, B.C. — submitted in November 2003. While it was the first time that C. gattii had been identified in a horse on the Island, it was only one of many cases included in the disease outbreak that began in 1999. Since then, 101 humans and more than 200 small animals have fallen ill with a unique version of cryptococcosis that can cause upper respiratory infection, acute neurological disease and even death. So far, four humans have died from cryptococcal disease while more than half of the pets diagnosed with C. gattii have died or have been euthanized. Based on the number of cases and the involvement of multiple species, researchers describe the Island outbreak as an unprecedented emergence of C. gattii. In December 2004, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Center for Emerging Issues issued a notice about Vancouver Island’s C. gattii outbreak, citing that “the emergence of this ‘tropical’ fungus and its ability to colonize on Vancouver Island stresses the importance of worldwide monitoring of its distribution. Particular focus should be given to those areas that have climactic and ecological attributes similar to eastern Vancouver Island.” Cryptococcal disease isn’t new to the Island, but this latest outbreak is different than the disease’s classic form. “First off, we’re seeing a lot more cases as well as a full spectrum of cases. Secondly, all were clustered in a region on the east coast of Vancouver Island,” explains Stephen, who conducted a case control study involving 36 companion animal patients from local veterinary clinics in 2001. His findings helped him and scientists at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control recognize that most of the human and animal cases were part of a larger “cluster” near Parksville and Rathtrevor Beach Provincial Park on the Island’s east side. The researchers eventually confirmed that all of the cases, which involved healthy people and animals, were caused by C. gattii — formerly classified as the gattii variety of Cryptococcus neoformans. This tropical strain of the fungus has been detected in soil, air and tree samples taken from areas in the coastal Douglas fir region of Vancouver Island. These areas became target zones for Duncan as she began her EHRF-supported study in May 2004. Local equine practitioners helped her compile a list of clients’ horses living within a 10-kilometre radius of fungal “hot spots” identified by environmental scientists from the University of British Columbia. During July and August, Duncan collected superficial nasal swabs and a number of blood samples from 260 horses living within the targeted zones. She also gathered details about horses’ ages, health problems, amount of time spent outdoors and the length of time the animals had lived on owners’ farms as well as on Vancouver Island. While all equine blood samples tested negative for Cryptococcus organisms, laboratory technicians isolated the fungus in nasal swabs from four horses involved in the study. All of the animals lived near the community of Duncan, B.C., where human health officials have reported clinical cases of cryptococcosis and where researchers have identified subclinical exposure or infection in small animals and wildlife. “Finding Cryptococcus organisms in the horses’ noses but not in their blood suggests that these animals have been exposed to the fungus and that there’s a potentially higher level of the organism — plus a potentially higher exposure level — in that area,” explains Duncan. “That’s supported by findings in our small animal research and the wildlife sampling we conducted while we were testing horses.” When Duncan conducted a similar survey on 300 companion animal patients in 2003, she found that about two per cent of the pets tested positive for the fungus while showing no signs of the disease. In 2004, Cryptococcus organisms were found in nasal swabs taken from two grey squirrels living wild in the area near the sub-clinical horses. Island Fungus Makes EQUINE CONTACT 6 Horse Health Lines • Spring 2005 Horses on Vancouver Island may not be developing the clinical signs of cryptococcosis, but an epidemiological study confirms that the region’s horses are being exposed to Cryptococcus gattii — the same strain of fungus at the centre of an unprecedented disease emergence. Veterinarians haven’t identified any further clinical cases of equine cryptococcosis since 2003, and the fungus doesn’t appear to be as much of a threat to local horses as it is to companion animals and humans. However, from an epidemiologist’s perspective, the Island’s horses are still valuable information sources since they spend much of their lives outdoors and are “very representative” of the environment, explains Duncan. Based on her 2003 companion animal study, Duncan and her colleagues concluded that where an environmental organism is not uniformly present everywhere in a region’s environment, risk is increased if disruptions — such as logging or commercial soil disruption — redistribute the organism from its environmental niche. Increased levels of travel or activity in the Island’s “hot spots” for C. gattii also boost the likelihood of encountering the organism. “Compared to other areas on the Island, UBC researchers have found higher concentrations of Cryptococcus organisms in environmental tests taken in the Duncan area — information that was confirmed by our findings in horses,” says Duncan, now a PhD student at Colorado State University. “We’re not saying that everyone should go around swabbing horses’ noses, but if the organism is isolated from an animal, we know the source is the environment. And if the animal doesn’t travel, we know the source of the fungus is in the immediate environment.” It’s one more way that veterinary research has helped human medical scientists understand this unique spread of cryptococcosis, says Duncan, who worked closely with scientists at UBC and at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control throughout her investigations. Within the next year, Duncan hopes her work will help even more researchers gain valuable knowledge of Vancouver Island’s C. gattii outbreak: the international journal Medical Mycology has published one of her articles while several others are in the review process at other medical and veterinary publications. For more information, visit the B.C. Centre for Disease Control at www.bccdc.org (click on Health Topics, A-Z). Students Share STUDIES at AAEP While Sylvia Carley and Jodyne Green picked up knowledge at the American Association of Equine Practitioners’ annual convention in December 2004, the student scientists also shared some new equine reproduction findings with veterinarians from around the world. Carley and Green, third-year veterinary students at WCVM, travelled to the convention in Denver, Colorado, to present research papers based on equine reproduction projects they helped to conduct as first-year undergraduate students during the summer of 2003. The students assisted equine reproduction specialist Dr. Claire Card with several projects that focus on assisted reproductive technology in horses. Card’s research team holds a multi-year, multi-project grant worth $277,911 from the Alberta Agricultural Research Institute. WCVM’s Equine Health Research Fund has also supported several aspects of Card’s reproductive research. Nearly 6,300 veterinary professionals, exhibitors and guests attended the AAEP’s 2004 convention that included close to 100 scientific presentations. “The AAEP accepted both papers for publication in the AAEP’s convention proceedings and for presentation at the December meeting,” explains Card. “We were told that many papers were entered in this competition since this was AAEP’s 50th anniversary convention, so we’re really very proud of Sylvia and Jody for going this far.” Frozen semen not inflammation source Frozen semen has gained a reputation in the horse breeding industry for causing acute post-breeding uterine inflammation in mares, and as a result, lower pregnancy rates. But based on their research, Carley and Card Continued on page 15 Above, from left to right: Sylvia Carley with Dr. Claire Card and Jodyne Green. Carley and Green worked with the equine reproduction specialist on several studies at WCVM’s Goodale Research Farm during the summer of 2003. Western College of Veterinary Medicine 7 The Future is WIDE OPEN in Equine Dentistry Imagine a visit to your dentist without the usual request of “Open wide.” Sounds strange, but it’s nothing new in the horse industry. Veterinarians have been examining and treating horses’ teeth through the partially-open mouths of their reluctant patients for centuries. But times are changing. The wideopen mouth of a horse is now one of the most visible signs of equine dentistry’s evolution. Since the introduction of safer sedatives and fast-acting general anesthesia drugs in the past two decades, a growing number of veterinarians are opting to use traditional tools like the full mouth speculum to identify and treat dental pathologies. “The full mouth speculum gives you a complete view of the horse’s mouth so you can pick up on any dental problems, and you can show the horse’s owner exactly what you’re seeing,” explains Dr. James Carmalt, a surgical resident at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM). Despite the tool’s benefits, some experienced veterinarians prefer to work without it. While that won’t make a difference in most cases, Carmalt says it means clinicians may overlook dental pathologies that they can’t feel or see (or a combination of the two) in their patients’ mouths. One example is the diastema (an abnormal gap between two cheek teeth in the same arcade). While people have known about this painful oral condition for more than 160 years, no one (other than a German veterinary dentist in the 1940s) has treated the problem. “Diastemata (plural of diastema) are extremely difficult to diagnose and treat without a complete oral examination. Horses often suffered and wasted away without anyone realizing the problem,” explains Carmalt. “The only way you can identify diastemata is with a full mouth speculum because you need to feel them and see them. They’re fairly rare, but at the same time, better drugs and equipment are allowing veterinarians to identify this problem and do something about it.” The full mouth speculum is also helping veterinarians put new equine dentistry knowledge to work in the field. In the past 15 years, scientists like Drs. Paddy Dixon and Ian Dacre of the University of Edinburgh have conducted fundamental research that has finally given practitioners an advanced picture of the horse’s dental micro-anatomy, how equine teeth erupt, the mouth’s blood supply and of common dental pathologies. “Scientists have produced more research articles and case reports about equine dentistry in the last two decades than what has been written in the last two centuries,” says Carmalt. Above: A full mouth speculum gives a clear view inside a horse’s mouth. Right: Surgical resident Dr. James Carmalt uses a motorized dental instrument to float a horse’s teeth. 8 Horse Health Lines • Spring 2005 ADVANCED INSIGHT, ARCHAIC PRACTICES On the surface, it looks like today’s veterinarians have all they need: a primary knowledge base of equine dentistry, plus access to safer and more effective anesthesia drugs. They also have the option of using motorized dental instruments — tools that have had a significant impact on the way veterinarians perform equine dentistry. “We can now float a horse’s teeth significantly faster than the 10 to 15 minutes it takes to do it manually,” says Carmalt. The machines are also very consistent: if veterinarians are floating the teeth of multiple horses at one farm, the quality of each procedure isn’t affected by operator fatigue. But when it comes down to putting practical dentistry into action, Carmalt points out that not much has changed: the profession still relies on many inefficient practices and anecdotal evidence. For example, many veterinarians still “punch out” horses’ teeth rather than pulling them out through the mouth. Although the latter method was the first to be put in practice, veterinarians began punching out horses’ teeth to save time and effort. Now, the profession is gaining a renewed appreciation for the original extraction technique. “It takes more time, skill and patience to pull a horse’s tooth through the mouth, but we can avoid problems associated with punching out teeth such as leaving tooth fragments behind,” Carmalt explains. Research is in high demand, but “Scientists meagre funding and a lack of controlled situations have deterred many have produced scientists from conducting clinical more research trials to study practical, dental issues and to test accepted practices. articles and case One of the few exceptions was reports about equine a western Canadian research team including Carmalt and Dr. Nadia dentistry in the last two Cymbaluk, director of veterinary decades than what’s research/field operations for Wyeth Organics. In 2001, the team worked been written in the last with 56 equine ranching horses to two centuries.” investigate the relationship between “These are the only three clinical trials of teeth floating published in equine dentistry, and that’s since the Chinese started aging horses in 630 B.C., so we truly are on the cutting edge.” feed digestibility and teeth floating. Contrary to conventional thought, the researchers found that floating makes no difference to feed digestibility — similar findings to two previous studies that were conducted in the U.S. and in Italy with smaller groups of horses. “These are the only three clinical trials of teeth floating published in equine dentistry, and that’s since the Chinese started aging horses in 630 B.C., so we truly are on the cutting edge,” says Carmalt. NEW AGE FOR AGE-OLD AGING SYSTEM? While researchers now have a better understanding of teeth floating’s true impact on feed digestibility, veterinarians still can’t definitively say whether dental care is integral to a horse’s performance — a question that horse people often ask. “The owners want us to float their horses’ teeth, check their mouths and make sure these animals have no dental problems before they deal with their behaviour problems,” says Carmalt, who regularly examines the teeth of young performance horses that have behaved badly during training. “It makes sense that bad teeth would limit performance, and there’s significant anecdotal evidence to say that is the case. But so far, there’s no scientific evidence.” Estimating horses’ ages is another area of interest for people involved in equine sports. For centuries, horse people have gauged a horse’s age by looking at the chewing surface of its lower incisors. This method is generally accurate until a horse is five years old, but after that, accuracy diminishes as the animal ages. Since many equine sports involve older, experienced performance horses, Carmalt believes there’s a need for a more accurate aging system — especially when veterinarians must estimate horses’ ages for prepurchase examinations. To achieve a higher level of accuracy, Carmalt is developing a new system where veterinarians look at the specific length of the enamel ridges on a horse’s cheek teeth. “The challenge is we need to copy that ridge from the tooth on to another medium — tracing paper, dental amalgum or a photo — where we can physically measure the length of the ridge and compare it to our mathematical models.” When can horse owners expect to see the new aging system in place? Not for awhile, says Carmalt, who must test the system’s accuracy on a large number of live horses with known ages before it’s considered a viable option. More work also needs to be done to make the aging system more practical. But if it proves to be an accurate approach to estimating horses’ ages, this will be one more step in the evolution of equine dentistry — a centuries-long process that is finally gaining momentum around the world. The specialized area is also gaining a larger following of veterinarians who are eager to contribute to its progress whether it’s in the research laboratory, out in the field, or in the classroom. At WCVM, Carmalt is one of several veterinarians who organizes an annual morning of voluntary lectures on equine dentistry for third-year veterinary students. After lunch, students try their hands at manually floating the teeth of the College’s palpation mares. “They have to know what it feels like to manually float teeth and to have respect for the soft tissues in a horse’s mouth. The other reason is that the majority of veterinary clinics out there don’t use motorized dental tools so they need to be competent at doing the job manually,” explains Carmalt. He adds that students gain more experience in diagnosing and treating dental pathologies during clinical rotations in their final year. Because equine dentistry is changing so rapidly, undergraduate students aren’t the only ones keen on taking a closer, more informed look inside the horse’s mouth. A case in point is Carmalt who learned how to perform root canals in horses during a recent endodontic course. “Root canals have been out there for four or five years. However, the treatment of incisor and canine teeth is significantly more successful than the treatment of cheek teeth due to their complex anatomy,” explains Carmalt. “It’s now a service we can offer to specific cases where it’s crucial to the horse’s performance and a practice we can introduce to our students.” What’s amazing is that scientists didn’t completely understand basic equine dental anatomy 20 years ago, and now, high-tech root canals for horses are a reality. Equine dentistry’s future truly is wide open. “Everybody is learning new things: we’re putting some of the old myths to rest and at the same time, we’re generating more questions that need to be tested,” says Carmalt. “If anyone is interested in learning more about equine dentistry, there’s no excuse anymore — it’s all there.” Want to read “Feed + Floating = Healthy Horse?” and other dentistry-related articles? Visit www.ehrf.usask. ca and click on to Horse Health Lines (Fall 2002) in PDF format. Western College of Veterinary Medicine 9 Scratches, &Moose Ticks RINGWORM Western Canada’s most common (and not so common) skin conditions. D r. Sue Ashburner still shudders when she describes the sight of one of her equine patients covered with thousands of bloodsucking ticks last winter. “We occasionally see wood ticks on horses during May and June, but I didn’t know what kind of ticks would be on horses in February,” admits Ashburner, a veterinary clinician at WCVM’s Large Animal Clinic in Saskatoon, Sask. Dr. Lydden Polley, a parasitologist at the College, soon solved the mystery: he identified the parasites as Dermacentor albipictus (Acari: Ixodidae), more commonly known as moose ticks. “It was the first time I ever saw a horse in this area covered in moose ticks,” says Ashburner. “That’s what I like about working on dermatology cases. There are always new things, and those cases challenge you to find out what you’re dealing with. Sometimes we never know the cause, but we usually know how to treat what we see.” At least once a week, Ashburner gets a chance to use her dermatological know-how on equine patients living around Saskatoon — an area that’s populated with horses of all breeds and disciplines. The clinic’s number of dermatology cases usually rises in the spring after horses shed their coats and owners suddenly notice lumps, bumps, growths or parasites that have shown up during the winter. Thanks to advances in diagnosing and treating equine skin conditions, veterinarians can offer clients more effective therapies and more understanding of what causes skin problems to develop. Most clients call for advice or to arrange for a veterinary visit, but some still insist on using their own home remedies that often makes Ashburner’s job tougher. “After they’ve scraped it, treated it or used ointments that burn the skin, it doesn’t look anything like it originally did. These remedies usually just make things worse.” While Ashburner isn’t expecting another moose tick infestation case soon, here are some common skin conditions that she and veterinary pathologist Dr. Ted Clark regularly see out in the field and in the pathology laboratory. Their comments accompany some additional information gleaned from the text, Equine Dermatology, co-authored by Drs. Danny Scott and William Miller Jr. • Dermatophytosis or ringworm is a fungal infection that’s transmitted by contact with infected hair, bedding, tack and grooming equipment. Ashburner often diagnoses multiple cases of ringworm in young horses living in close quarters throughout the winter months: the infection often goes unnoticed until horses shed their winter coats. The most consistent clinical sign is one or many circular patches of alopecia (hair loss) with variable scaling and crusting. But horses may also 10 Horse Health Lines • Spring 2005 develop the classic ring lesion with a healed centre and fine follicular papules and crusts on the ring’s edges. Lesions are usually multiple, and they’re most commonly found on the face, neck, the sides and girth. The lesions usually go away within three months, but veterinarians often use topical and systemic treatments to help their patients’ response to the infection, to reduce the spread of the fungus and to speed up the healing process. • Sarcoids are the most common skin tumour of horses around the world. Veterinary researchers believe the cause of sarcoids is viral, and research has shown that bovine papillomaviruses (BVP) are commonly involved in sarcoid development. Lesions frequently show up in areas of a horse’s body after a wound or trauma, or they may also spread to other areas of the same horse or to other horses through biting, rubbing, tack, equipment and insects. Sarcoids occur anywhere on a horse’s body, but most lesions are found on the head, neck and ventral body surface. The lesions’ appearance can be verrucous (wart-like), fibroblastic (proud flesh-like), mixed verrucous and fibroblastic, and occult (flat). Sarcoids do not metastasize, and some tumours may disappear after several years. Depending on available resources, veterinarians can choose from surgical excision, cryosurgery, radio-frequency hyperthermia, laser therapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy or combinations of treatments. • Papillomas present in two different forms: as warts (viral papillomatosis) or as aural plaque (ear papillomas). Viral papillomas spread through direct contact or indirectly through contact with contaminated equipment or housing. Young horses often develop clusters of warts, usually on their muzzles or lips. “They bother the owner much more than horses,” says Ashburner. “If left alone, they tend to go away and you can’t rush them. People always buy potions and lotions, but they usually make no difference.” Aural plaques — white-greyish crusts commonly found in horses’ inner ears — don’t respond very well to topical treatments, and they rarely go away. Fortunately, these lesions are only a cosmetic problem. • Eosinophilic granuloma or nodular necrobiosis is an equine dermatosis most commonly seen in the spring and summer. These nodules are round, elevated, and occur as single or multiple lesions on the back, withers and neck. The lesions aren’t painful or itchy, and the overlying skin and hair coat are normal. Veterinarians can surgically remove one or several lesions, or treat multiple lesions with systemic glucocorticoids over several weeks. Some lesions undergo spontaneous remission in three to six months, while older or larger lesions must be surgically removed. cream — to fight the mixed infection,” explains Ashburner. Clark adds that it’s important for veterinarians to be aware that scratches isn’t “one specific disease with one specific cause.” If certain horses or horse herds continue to be plagued by this type of dermatitis, practitioners need to look at the animals’ environment, their habits and what they’re used for to learn more about probable causes. • Allergic reactions show up as • Rain scald (dermatophilosis) anything from bumps and wheals in is a bacterial skin infection that causes all shapes and patterns to angioedema superficial, pustular and crusting (swelling) involving the muzzle, eyelids, dermatitis in horses. These lesions under the belly, legs or the entire body. are most commonly found on horses’ These reactions result from insect bites, rumps, saddle area, face and neck — or plants, drugs or vaccines, a change in on pasterns, coronets and heels (in the feed, bedding or the horse’s environment. form of scratches). Gathering a thorough medical history The two most important factors “That’s what I like about working on is how veterinarians usually track down the that lead to rain scald are skin damage dermatology cases. There are always and moisture. The condition is often source, says Ashburner. “It could be caused by a minor environmental change, a sudden new things, and those cases challenge diagnosed in horses after intense rain, and hatch of bugs in the area. It really pays off to you to find out what you’re dealing with. when temperatures and humidity are high. ask a lot of questions.” Veterinarians on the Prairies don’t often see Sometimes we never know the cause, rain rot, but it’s a common problem in B.C. Ashburner and her colleagues but we usually know how to usually try to eliminate the source of While most cases of rain rot go away hypersensitivity or generally treat the horse within a month, the best treatments include treat what we see.” to try and decrease its immune response. keeping the animal dry, removing crusts, and “One treatment that has worked quite well is to feed the horse raw linseed oil: using topical treatments and using systemic therapy if the infection is chronic its Omega 3 fatty acids help to decrease the animal’s hypersensitive response or severe. in the skin. That seems to calm things down and it helps to make the other • Insect hypersensitivity: Western Canadian horse owners and treatments work better.” veterinarians deal with fewer parasitic problems than in other parts of the • Scratches or pastern dermatitis most commonly affects one or both world because of the region’s cooler climate, but insect hypersensitivity is still hind limbs with varying levels of pain and itchiness. The condition initially a common problem in the spring and summer months. Controlling insects shows up as erythema (dew poisoning), swelling and scaling on the pastern, and using anti-itching agents can help to manage insect hypersensitivity. The then progresses to discharge, matting of hair and crusting. use of ivermectin, moxidectin and other dewormers has also helped to reduce Veterinarians usually diagnose this problem when there’s abrasive mud the occurrence of conditions like sweet itch, says Ashburner. in corrals, or when ice crystals are mixed in the snow and dirt. “We think - Sweet itch or Summer Seasonal Recurrent Dermatitis (SSRD): The most the moisture content has something to do with it: something seems to set important cause of equine insect hypersensitivity is Culicoides gnats (sandflies, up the right environmental conditions to induce scratches, particularly in no-see-ums, biting midges). Affected horses develop itchy, crusted papules on the spring,” says Ashburner, adding that the condition usually shows up on a the top of their tails, along their mane, neck, withers, hips, ears and forehead. white leg. The disease’s itchy nature causes horses to scratch and chew at themselves, “It responds very well if treated early, but it’s often missed by the owners or they may rub against stalls or fences. That can lead to hair loss, ulcer until the horse’s pastern is very sore or very swollen. And the longer they development and damage to the animals’ manes and tails. have it, the harder it is to treat.” Severe cases of scratches can also lead to - Mange is caused by mite infestations in horses’ coats. Owners and a longstanding, immune-mediated infection called vasculitis that can take veterinarians usually see these infestations during the late winter and early months to cure. spring, and contributing factors include crowding, prolonged stabling, and If diagnosed early, the ideal treatment is to clean the area very well with poor nutrition. mild soap (no abrasive cleaners) then remove as much of the scabby debris - Lice infestations are commonly found in horses during the winter when as possible. Clipping the hair can help to remove the scabs. “We keep the the animals’ coats are longer and they may be in close contact with their herd area dry and use a topical cream — a combination of antibiotic and steroid mates. Biting lice are usually found on the horses’ dorsolateral trunk, while sucking lice prefer the animals’ mane, tail and fetlocks. Clinical signs include Left: A case of pastern dermatitis (scratches). Top: Young horses often develop scaling, a dishevelled coat, hair loss and mild to moderate itchiness. clusters of warts, usually on their muzzles or lips. Centre: Rain scald-associated lesions are most commonly found on horses’ rumps, saddle area, face and neck. Western College of Veterinary Medicine 11 Skin-deep ATTRACTION Dr. Danny Scott had only scraped the surface of his lecture topic when he stopped to make something very clear to his listeners. “There isn’t anything I’d rather do than see, hear and talk about skin disease — because nothing rocks more than skin disease,” declared the Cornell University veterinary professor with a wide grin. Scott’s infectious enthusiasm for his profession drew laughs, plus plenty of admiration from his appreciative audience. Few people in the world know as much about veterinary dermatology as Scott does, explaining why his name is associated with dermatological “bibles” such as Small Animal Dermatology, Large Animal Dermatology, and most recently, Equine Dermatology. In January 2004, Scott spent a week in Saskatoon as one of WCVM’s D.L.T. Smith guest lecturers. “In the last 25 years, Danny Scott has taken veterinary dermatology from ‘orphaned disdain’ to an organized specialty,” said Dr. Sherry Myers as she introduced the skin specialist, researcher and diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Dermatology to his audience. Back in Ithaca, New York, Scott uses his three decades of experience to diagnose and treat challenging skin diseases in dogs, cats and horses on a daily basis at Cornell University’s Hospital for Animals. His specialized training in dermal pathology also enables him to gain a microscopic view of his patients’ skin problems. And just why is he so passionate about studying skin? “Because it’s all just hanging out there. The gross pathology is right there before your eyes: you can see it, you can smell it, you can feel it, you can taste it. It’s all right there for the taking,” Scott explained to Horse Health Lines. “The owners see their pets’ skin, too — so it’s obvious to them if you’re making a difference or not. It’s quite a humbling specialty because you can’t hide anything from anyone.” 12 Horse Health Lines • Spring 2005 Q How did you become interested in veterinary dermatology? When I went through veterinary school at the University of California Davis, my favorite veterinary professor was Dr. Tony Stannard. Then, when I came out to Cornell to do my internship in 1971, I met Dr. Bob Kirk who continues to be my Dad-away-from-home and the best veterinarian, the best people person and the nicest guy I ever met. Those two people really intrigued me and both happened to be dermatologists. The other thing that really interested me was that veterinary dermatology was such a black hole. So many conditions had no names, so many therapies were totally anecdotal and not based on any disease understanding. For example, when I graduated, there was about 50 known skin diseases. Now, there are over 500. There has been an explosion of information, and it’s been exciting to be part of that. I liked the challenge of the unknown: trying to push the frontier and remove some of the mysticisms surrounding veterinary dermatology. Q What helped you understand veterinary dermatology? About nine years after I came to Cornell, I took my first sabbatical at the University of Minnesota’s medical school in dermatology. I went to specifically study skin pathology because at that time, no one in veterinary medicine had formal training as a dermal pathologist. Like many other people, I had taught myself dermal pathology, but I really wanted to see what could happen at a higher level. I spent a year looking at human skin biopsies through a microscope, and it was probably the single most explosive, professional growth year for me. I saw things and heard about things that never occurred to me. I came back tremendously enriched, and that was when I started developing the pattern analysis approach to veterinary dermal pathology which is now an institution. That all stems from my experience in human dermatology. It broadened my understanding, my appreciation for dermatology. It also increased the number of diagnoses I could make — because it’s pretty difficult to diagnose something if you don’t even know it exists. Above, left to right: A close up look at an equine sarcoid; hyperextensible skin is a clinical sign of hyperelastosis cutis; a horse that has lost large amounts of telogen (resting) hairs; draining an atheroma — a cyst of the nasal diverticulum or false nostril. Facing page, top: Serum scalding after an injection. Centre: Skin sores developed all over this horse’s body when its owner forgot to rinse off shampoo after a bath. Q What makes dermatology so tricky? Part of the challenge is that as an organ and as a tissue, skin has a limited number of reaction patterns. In other words, skin has a limited number of ways that it can react to billions of stimuli. In the eyes of most veterinarians (other than dermatologists), many skin diseases tend to look the same, so unless you spend a long time picking up on the nuances, these conditions can lead you down a merry path over and over again. As a specialist, it’s not unusual for me to see a patient who has been examined by four to six veterinarians, who has had a double-digit number of diagnoses made by one or more people and who has been through all kinds of unsuccessful therapies. It was Goethe that said, “What is the most difficult of all? That which seems to you the easiest, to see with one’s eyes what is lying before them.” That’s particularly apropos for dermatology. Equine dermatology doesn’t have any corner on the anecdote market, but it’s an area that has certainly been rife with them over the years. Frankly, there aren’t enough days or cases to address all of them in my lifetime. But every once in awhile, I’m confronted with one that seems to work into my plan for the next year, so we’ll set up some kind of pathological or therapeutic routine to address that particular anecdote. It’s fun to show whether these anecdotes are the truth or not, and I must confess that it gives me a cheap thrill to blow one of those things out of the water! Q What does it take to be a good veterinary dermatologist? You have to be a person whose selfimage and daily goals aren’t based on instant gratification because those little moments don’t come along very often in dermatology. If you’re an orthopedic surgeon, you fix the problem and then you may never see that particular patient again. But many of these chronic skin conditions require a lot of client education, a lot of phone time, and a lot of temporary frustrations as things spiral out of control in a particular month. The gratification may be borne out over seven to eight years when one of your patients finally dies of a natural cause and the owners tell you how much they appreciated the time you took on the phone or the time you spent tweaking the treatments. Q What can veterinarians do to ensure more accurate diagnoses? If there’s one place where practitioners come up short, it’s that they just don’t accumulate their patients’ histories. Everything is an important piece of the puzzle. If you have a really good history, that history could eliminate nine of the 10 possible diseases and give you the most likely diagnosis. Of course, I do understand that time and money are issues when you’re in practice: it can take at least a half-hour and even longer to get a good history on a chronic case. Practitioners often don’t have time to go back to the beginning, come up to the present and take a few side trails. On the other hand, that extra time could save them a lot of frustration. Q What’s your clinical work like? I spend a lot of time teaching students and diagnosing skin diseases, but another part of my job is to give my clients long-term prognoses. Because of the types of diseases that I deal with, I have to let them know that we’re not going to cure this condition by November 2005 and that we’ll become very good phone pals through the ups and downs of these diseases. Many skin conditions aren’t curable: they require lifelong management so we may need to tweak our therapies from month to month or year to year based on factors such as higher levels of pollen or mould spores in the air. Q How do you choose research topics? A lot of what I publish is about microscopic nuances that I notice as I look at interesting patients and various things. I start formulating these little, anecdotal “gut feelings,” then I convince some resident to work on my idea, confirm my gut feeling or blow it away, and we eventually get the work published and push the frontier a tad. For more equine dermatology stories, visit www.ehrf.usask.ca and click on to Horse Health Lines (Fall 2004) and related articles. THE GALLOPING GAZETTE WCVM Presents In January, Dr. James Carmalt gave a talk entitled “Does dental care affect digestion?” at the 2005 Alberta Horse Breeders and Owners Conference in Red Deer, Alta. Two months later, Carmalt was also one of several WCVM representatives who took part in the Saskatchewan Horse Federation’s annual conference where the organization celebrated its 30th anniversary. During the conference’s horse health and welfare section, Carmalt gave a presentation called “Colic: is it as bad as it seems?” while Dr. Trish Dowling gave the veterinary point of view in a panel discussion called “The good moving horse.” Other featured speakers included veterinary pharmacologist Dr. Chris Clark and internal medicine specialist Dr. Katharina Lohmann. Continued on back cover Western College of Veterinary Medicine 13 M ore than seven tributes: lifetime memberships decades ago, an in the National Cutting Horse Edmonton, Alta., Association and the American teenager wrote an essay in Quarter Horse Association, high school about his ambition and the title of honourary viceto own a farm and to build a president with AQHA. life for himself that revolved George’s most prized horse around horses, cattle and the was a son of King P-234 called country. It took a few more Fred B. Clymer — a talented years for that young man to cutting horse that earned fulfil his dreams, but the words sixth place in the NCHA’s written by George Golden’s 1966 World Championships. teenaged self essentially charted The stallion also received the the course of his life. NCHA Bronze Award and was “The farm was always classed as one of the AQHA really special to George. As Superior Cutting Horses a boy, he used to spend all with an impressive record of of his summers at his uncles’ four halter points and 101 farms near Lavoy (Alta.) and performance points. that’s when he decided to be “George mainly competed a farmer,” explains Eleanor in cutting horse competitions, Golden. Eleanor first met her and all of the girls competed future husband while she was in horse shows when they visiting the sisters of Stuart were younger,” recalls Eleanor, Hart, and George was working who prepared meals and clean out with the famous wrestler. outfits for her husband and The couple eventually daughters during competitions. married in 1941 and lived George even took a couple of in Vancouver, B.C., until daughters on longer treks to George joined the Canadian compete in Ontario and the Navy for a year and a U.S. “He really enjoyed those half. After returning from summers on the road. We won overseas, George established a so many trophies, we didn’t construction firm called G.W. know where to put them all.” Golden Construction Limited It was during these busy in Edmonton — the first of years when George became a series of successful business acquainted with the Western ventures in construction, saw College of Veterinary Medicine milling, lumber production and and its future plans for equine ranching that he developed health research and advanced during his lifetime. veterinary training. After The Western College of Veterinary But the business closest to chairing the College’s equine Medicine’s Equine Health Research Fund his heart was the family’s ranch research advisory committee located 24 kilometres east of pays tribute to one of its founders — George from 1971 to 1974, George was Sherwood Park, Alta. After of four Alberta horsemen Golden. The Alberta horseman passed away one buying the property in the who contributed $15,000 each on October 16, 2004, at the age of 88. late 1940s, George built a new to establish WCVM’s Equine ranch home for Eleanor and Health Research Fund in 1977. their four daughters — Patricia, Doreen, Nadine and Elaine — in 1954. George continued to serve as a member of the Fund’s advisory board until While George took pride in raising beef cattle, it was his horses that 1983. earned him special recognition. He was one of the first to breed and show “We were all just interested in the horse business and in the health Quarter horses in Western Canada, and from the 1950s to 1980s, the of horses,” explained George during an interview for the Fund’s 25th Golden name became synonymous with champions in Canada’s Quarter anniversary in 2002. “We were just trying to help.” horse industry and on the Western horse show circuit. George’s longtime Above: George Golden astride his mare, Pepsi Clymer, after winning first in a involvement in the Quarter horse industry also earned him several major GEORGE GOLDEN, 1916-2004 GOLDEN YEARS Western Pleasure class. 14 Horse Health Lines • Fall 2004 “He was just a very down-to-earth, friendly person who was interested in veterinary medicine, in horses and in bettering their lives.” But George provided much more than financial support to the fledgling organization. “The Fund’s future relied on whether Western Canada’s horse community would rally around this idea and support it,” points out Dr. Ole Nielsen, WCVM’s dean from 1974 to 1982. Nielsen also initiated the development of a regional equine health research fund. “Prominent horse people like George who volunteered their time, leadership skills, and their influence were crucial to the Fund’s success.” Besides supporting EHRF, George often trailered his Quarter horses to WCVM’s Large Animal Clinic for specialized care. One faculty member who often worked on the rancher’s mounts was Dr. Peter Fretz. In particular, the surgical specialist recalls meeting George soon after returning from a 1980-81 sabbatical leave at Colorado State University with Dr. Wayne McIlwraith — a world-renowned specialist in equine arthroscopy. “I took a large fragment of bone out of the hock of one of George’s horses, and afterwards, he asked me how it went. I mentioned to George that we could have done the same surgery with an arthroscope — except we didn’t have the equipment at WCVM.” Shortly after, Fretz was amazed to hear that George had sent a $25,000 cheque so WCVM could purchase its own arthroscope and begin offering horse owners the minimally-invasive technology as an option to traditional surgery. Having the equipment at the College also enabled Dr. Mark Hurtig — the Equine Health Research Fellow from 1982 to 1984 — to develop arthroscopic techniques during his surgical residency. Another of George’s unexpected gifts to WCVM was an exercise treadmill — worth more than $7,000 — that was used to walk equine clinical patients. “I’m sure he just looked around and saw that we didn’t have any proper exercise equipment, talked to a few people, then decided to purchase it. We certainly didn’t ask him for it, but that was just the way he liked to do things,” says Nielsen. “When the Fund’s travelling equine health seminars came to Alberta, George always came, he was always one of the first to write a cheque, and he always set the standard,” adds Fretz. “He was just a very down-to-earth, friendly person who was interested in veterinary medicine, in horses and in bettering their lives.” Those recollections make Eleanor smile in agreement. “There was nothing George liked better than talking to people. He was always interested in what people were doing and planning — and that was usually what convinced him to help out.” Besides WCVM, many people and organizations — including an Edmonton hospital and several local churches — benefited from George’s generous nature. “He did a lot of good in his day, and he was pretty thoughtful in his ways,” says Eleanor, his wife of 63 years. Five years ago, George and Eleanor moved into a Sherwood Park condominium where they enjoyed countless visits with their daughters and their expanding families of 12 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. And even when illness prevented George from visiting his beloved ranch, his keen mind never stopped running the place — never stopped picturing the cattle, the horses, the crops, the hay land, everything. “All he ever wanted was to own a farm, and he got it,” says Eleanor. Indeed, George Golden got it. AAEP cont’d from page 7 say frozen semen doesn’t deserve the bad rap: their 2003 study demonstrated that breeding with one full dose or two half doses of frozen semen did not significantly increase the amount of bacteria, endometrial debris and the percentage of neutrophils measured in uterine lavage samples. Those findings come from a WCVM project that involved 37 young, fertile mares separated into three groups. While control mares received no breeding treatment, Carley and Card bred the second group of mares with a single dose of frozen semen on the day of ovulation. The research team bred the third group with two half-doses of frozen semen: one breeding at ovulation and another breeding 24 hours later. The scientists collected low volume uterine lavage samples 24 to 96 hours post-breeding during a total of 40 cycles, and relied on the expertise of veterinary microbiologist Dr. Manuel Chirino-Trejo to analyse slides for bacteria. “There was no significant difference between the control group and the single breeding. The neutrophil counts in the singlebred mares were no higher than four per cent — what you would expect in a mare that had just been bred — and any inflammation that may have been present had resolved itself very quickly after the single breeding,” says Carley. She adds that while the second group of horses did have higher amounts of bacteria, endometrial debris and neutrophil percentages than the single-breeding mares, the differences weren’t significant. The same study also helped researchers set a baseline for the normal range of endometrial cytologic parameters — valuable information that can help practitioners evaluate mares postbreeding. Based on their findings, Carley and Card say that an average neutrophil count of five per cent following breeding is normal for mares selected for good breeding potential. “Any time a veterinarian evaluates a mare 24 hours after being bred with frozen semen and sees anything more than an average of five per cent of neutrophils on the slide, it indicates that there’s a problem,” says Card. “That’s important because until this point, nobody knew what the magic number was.” Fits to a T Green’s paper described the effects of using inexpensive controlled intravaginal drug release (CIDR) to synchronize estrus in large herds of horses. The key part of this method is a T-shaped plastic device that releases progesterone intravaginally for up to 14 days in mares. While owners have been concerned about whether the CIDR device affects mares’ fertility, Green found no difference in pregnancy rates among horses that used the device and those that didn’t. However, minor side effects (small amounts of vaginal discharge and urine scald) could potentially cause complications in mares that have past breeding problems. As a result, Green and Card advise that the CIDR devices are best suited for use in mares without a history of breeding problems (see the Spring 2004 issue of Horse Health Lines at www.ehrf.usask.ca to read more about CIDR research). Western College of Veterinary Medicine 15 THE GALLOPING GAZETTE (cont’d) Veterinary Teamwork In January 2005, Dr. James Carmalt leapt out of his hectic life as a surgical resident at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine to jump into another demanding job: Canada’s team veterinarian at the 2005 Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) World Endurance Championships in Dubai, UAE. Carmalt was certainly qualified for the role: he became an FEI-certified endurance racing veterinary judge nearly two years ago and has served as a foreign delegate at several U.S. endurance races. As well, Carmalt was Canada West’s team veterinarian for the 2003 Pan American Endurance Championships at Mount Adams, Washington, where the team won a bronze medal. “They’re two very different roles, and it’s nice to have experience on both sides of the fence. I know what the judges are looking for when I bring my team’s horses forward at these world events, and if I wouldn’t pass a horse, chances are the judges will share the same opinion,” says Carmalt. At 6 a.m. on January 27, 178 horses and their riders from 41 countries started in the 160-kilometre (100-mile) endurance race across the Arabian desert. Just over seven hours later, the race’s leaders crossed the finish line to win the largest FEI event ever held. Altogether, 61 horses and riders completed the race including three of the five Canadian competitors. Those results earned Team Canada a fourth place in the world championship’s team event — an incredible accomplishment, says Carmalt. “It was a flat race, and the Arabs run flat horses very well. In contrast, we tend to have general-purpose and mountaintype horses, so our team came from competing at Mount Adams to the extreme opposite in terrain at Dubai and won fourth overall. I’m extremely proud of them.” Other than the flat terrain, Carmalt says the desert climate didn’t cause any difficulties for the Canadians. “Beforehand, we worked on some of the horses’ little niggling problems, but once race day came, we just had to accept that what will happen will happen — and you just deal with it. That’s no different whether you’re at the World Championships or at a local race.” During the race, Carmalt gained valuable experience in identifying lamenesses in endurance horses — including subtle injuries that only became evident after a certain number of miles. “There were nearly 180 horses in the race and each horse ‘trotted out’ (part of the veterinary examination process) about five times throughout the entire competition. That’s nearly 1,000 trots within a 13-hour period, so it was an incredible chance to improve your ability to detect signs of lameness.” It was also the ideal opportunity to watch how other teams managed their horses during the race’s mandatory veterinary checks. “It was very interesting to see how the crew dynamics worked in other teams like the HORSE HEALTH LINES Horse Health Lines is a publication produced by the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s Equine Health Research Fund. Articles from Horse Health Lines reprinted in other publications should acknowledge the source. Please send questions or comments to: Dr. Hugh Townsend, Editor, Horse Health Lines WCVM, University of Saskatchewan 52 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5B4 Tele.: 306-966-7453 Fax: 306-966-7274 wcvm.research@usask.ca UAE team that descended on one of their horses like a Formula One pit crew. Literally, within 30 seconds, their horse was bare naked and being cooled.” But what Carmalt will never forget was the unique opportunity to see the world’s most elite endurance horses perform at the sport’s highest level. “For example, I remember watching the French rider who was five minutes behind the first group of horses just before the race’s final stage. In that final loop, her horse galloped flat out, with no whipping or spurring. Their average speed was 31 kilometres per hour — and this was after already running 141 kilometres of the race. It was just incredible to see that calibre of horse perform its best.” WCVM Presents In October 2004, Dr. Spencer Barber spoke about racetrack injuries at the Canadian Racetrack Officials conference in Saskatoon, Sask. In January, Barber travelled to Orlando, Florida, to give five presentations on different aspects of wound healing at the North America Veterinary Conference. Last fall, Horse-Canada published an article called “Proud Flesh: When Granulation Goes Wild” that was based on writer Nicole Kitchener’s interview with Barber. As well, one of Barber’s articles called “Managing Fractures of the Facial Bones in Horses” will appear in the Spring 2005 issue of the Veterinary Wound Management Society’s newsletter. Above: The scene shortly before 178 horses and their riders begin the World Endurance Championship race at 6 a.m. on January 27. Right: Myna Cryderman and her Arab mare, Night Skye, were the first members of Team Canada to finish with a time of 11 hours, 10 minutes and 13 seconds. Canada’s Yvette Vinton and Daphne Richard also finished the race — earning fourth place for Canada in the team event. Check out Horse Health Lines on line at www.ehrf.usask.ca PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40112792 RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO: Research Office, WCVM University of Saskatchewan 52 Campus Drive Saskatoon, SK S7N 5B4 wcvm.research@usask.ca