This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from... of Economic Research

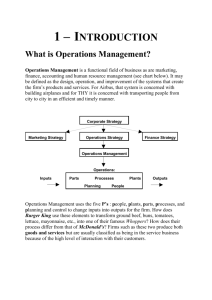

advertisement