Strategic Responses to Hybrid Social Ventures Please share

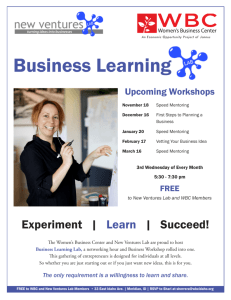

advertisement