Age-biased Spring Dispersal in Male Wild Turkeys

advertisement

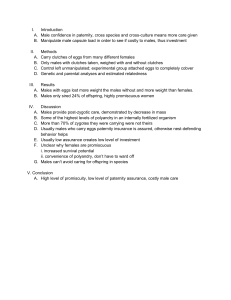

The Auk 113(1):240-242, 1996 Age-biasedSpring Dispersal in Male Wild Turkeys ALEXANDERV. BADYAEV? 3 WILLIAM J. ETGES, 1 AND THOMASE. MARTIN2 •Department of Biological Sciences, University ofArkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701,USA;and 2MontanaCooperative WildlifeResearch Unit, Universityof Montana,Missoula, Montana59812,USA In polygamousanimal species,the reproductive componentof male fitnesslargely is determinedby the number of femalesto which they can gain access (e.g. Wright 1946).Accessto femalesoften is strongly influencedby the possession of high-qualitybreeding or display groundsby males(Weatherheadand Rob- female renestingand breedingreceptivenesscauses changesin distribution of females. Methods.--Ourstudywas conductedduring 19921993 in the Ozark National Forest in northern Ar- kansas.The study sitewas flat-toppedhills (elevation to 746 m) with narrow valleys.Dominant canopyspe- ertson 1977). For animals that move between winter cies included white oak (Quercusalba), northern red and breeding areas,accessto high-quality breeding or displaygroundscan be determinedby timing and distanceof suchmovements,but ability to hold highqualitysitescouldbe determinedby localfamiliarity, aswell associaland physiologicalstatus(Greenwood oak (Q. rubra),postoak (Q. stellata),shagbarkhickory (Caryaovata),and shortleafpine (Pinusechinata).For a detaileddescriptionof the studysite, seeBadyaev (1995).All birdswere capturedusingcannonnetson pre-baitedsitesdistributedthroughoutthe studyarea. All capturedbirds were fitted with 120 g backpackstyle radio transmittersand releasedat capturesites. Most of the 35 radio-taggedmaleswere locatedonce every four to five days, although more frequent lo- 1980, Johnson 1986, Johnson and Gaines 1990, P•irt 1994, Tsuji et al. 1994). Early dispersal and short-distance movements should allow access to best sites and dominant indi- vidualsshouldbe expectedto exhibit suchmovement behaviors. Moveover, shorter dispersal can enhance the survival component of fitness becauseit often reducespotentialcostsof increasedmortalityriskwith dispersal distance (e.g. Johnsonand Gaines 1990). Subordinates,however, may be expectedto disperse longer distancesand move morewithin displayareas becauseit takesthem longer and more movement to cations and visual observations also were recorded. Only birds with 15 or more recorded locationswere usedto calculatehomeranges(for detailsof telemetry protocol,see Badyaevet al. 1996). Femalesinitiated80%of firstnestsby 1 May in both years.Thus, the period prior to 2 May is referred as "early" as opposedto "late," which extendsfrom 2 May to 2 June.Successive locationsseparatedby more find suitable areas from which a dominant individual than 2 days but lessthan 10 days were statistically will not exclude them. Here we examine this domiindependent (e.g. Swihart and Slade [1985] test for nance hypothesis. two-day intervals; t2/r2 > 1.85, P < 0.05) regardless Wild Turkeys (Meleagrisgallopavo)are especially of time lags between them. Observationsseparated suitable for study of potential effectsof dominance by five dayswere usedfor interlocationdistanceanalstatuson dispersaland movementpatterns.They are yses.The displayrangewasdefinedasthe homerange polygynous and, in females, nest-site selection preoccupiedfrom 1 April through 15 June. This time cedesmateselection(Healy 1992,Badyaev1994).The interval was basedon female nest-initiationphenolsocialstatusin thisspeciesis largelysetby age;young ogy (Badyaev1994).Dispersaldistancewas defined malesare subordinateto older malesand can be pre- as the distancefrom harmonicmean of home range vented from breeding by theseolder males(Healy usedin February to harmonic mean of display range. 1992).In addition,the useof radiotelemetryallowed Partial areawas calculatedassum of areasof all polyus to quantify female movementsduring springdis- gonsdrawn aroundcentersof activitydivided by the persal and distribution of nesting areas(Badyaevet total area of single polygon of range occupiedby an al. 1996). animal (Kenward 1990). Home-range estimates,inWe predictedthat: (1) older malesshould disperse terlocation distances, and associated statistics were the shortest distance; (2) movements of older males computedusing RANGES IV software(Kenward 1990; should concentratearound suitabledisplay grounds for details,seeBadyaevet al. 1996).Neither morpho(i.e. aroundlimited nestingareas;Badyaevet al. 1996) logical measurementsnor dispersalparametersdifonce they reach their display grounds, and should fered between study sitesor years (ANOVA, all P > encompassa smaller area than subordinates;and (3) 0.3).We usedthe criteriaof Kelly (1975)and Steffen if movementsof males in spring are influenced by et al. (1990) to classifymales into SY (secondyear displayingactivity, malesare expectedto move more after hatching), TY (third year after hatching), and and farther in later partsof the breedingseasonwhen ATY (after third year sincehatching)age groups. Results.--ATYmalesdispersedshorterdistancesthan either SY or TY males (Kruskal-Wallis test, X 2 = 7.45, 3 Present address:Department of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA. 240 df = 2, P < 0.05; Table 1). Dispersal distancesof SY and TY maleswere not significantlydifferent (X2 = 3.42, P = 0.12). Heavier SY males dispersedshorter January 1996] Short Communications andCommentaries 241 TABI.•1. Descriptive statistics(• + SE,with n and range in parentheses)of spring-dispersaland home-range estimatesof male Wild Turkeys in the ArkansasOzarks, 1992-1993. Age category Parameter' SY TY 6.8 + 1.7 + 3.3 + 4.9 + Spring dispersal(km) 5.1 + 1.0 (12, 1.1-12.6) Harmonic-meanrange (km2) 18.9 + 7.9 (5, 2.5-36.7) Multinuclear polygon (kin2) 6.9 + 1.6 (7, 2.1-12.7) Convex polygon (kin2) 10.7 + 2.8 (7, 2.1-18.9) ATY 1.4 (17, 0.5-22.2) 0.5 (9, 0.4-4.2) 0.9 (11, 0.9-10.8) 1.4 (11, 0.7-14.3) 2.6 + 0.7 (6, 0.4-4.7) 0.38 (1) 0.5 + 0.3 (3, 0.2-0.8) 0.9 + 0.05 (3, 0.92-1.0) ßHarmonic-meanestimate,multinuclearpolygon by clustering,and convexpolygon methodsbasedon 90%-probabilitypolygons. distances,and body massin springexplained59%of the variation in spring dispersaldistancein this age class(linear regression,F•,•2= 14.2,P < 0.005). Dispersaldistancesof TY and ATY malesdid not correlate with body mass(both P > 0.2). Display rangesof TY and ATY maleswere significantlysmallerthan thoseof SY males(Kruskal-Wallis from being closerto suchareasby assuringfrequent encounterswith females(seealsoBradburyand Gibson 1983, Schroederand White 1993). In the population under study, early nest initiation was the most important factor contributing to nest survival (Badyaev 1994). Thus, males that reach spring display groundsearliestprofit by mating with early-nesting test, X • = 8.35, P = 0.01; Table 1). This difference was females. mostapparentwhen harmonic-meanestimatesof disAdult malesoccupiedsmallerdisplayhome ranges than did SY males (see also Hoffman 1991). Adultplay range were used (P < 0.001; Table 1). Males of different agesuseddisplayrangesdifferently (Fig. 1). malehome-rangeusewasmoreheterogeneous, which Partial-area estimate differed between age classes possiblyreflectsan uneven distribution of suitable (Kruskal-Wallistest,X• = 3.61,P = 0.06)and averaged nestingareasof females(Badyaev1994,1995,Badyaev 0.49 + SE of 0.13 (n = 10, range 0.11-1.0) for adults et al. 1996). Adult-male movements within their dis(TY and ATY males combined) and 0.79 + 0.13 (n = play ranges were more restricted than those of SY 7, range 0.37-1.00) for SY males. Adult-male use of males, potentially becausenondisplaying SY males range was concentratedaround several centersof acexperiencereducedaggressionfrom older conspeciftivity (• = 1.8 + 0.2), but SY male range usewas less icswhen moving amongdisplaygrounds(e.g. Healy 1992). Adult males showed considerable fidelity to restrictedto particularareas.Rangeestimatesfor subadultsincreasedwith almost every additional ob- display siteswithin the breeding season(Fig. 1). Berservationbecausebirdsfrequently ventured into pregerud (1988) and Phillips (1990) also speculatedthat viously unvisited areas(Fig. 1). female forest grousespreferred males showing the For SY males, distances between successive loca- tions averaged 4.1 + 0.3 km late in the seasonand were significantlylonger than 2.2 + 0.1 km distances early in the season(pairwise t-test, t = 3.89, P = 0.02). However, there were no differencesbetween early (4.6 + 1.3 km•) and late (9.0 + 3.5 km•) home ranges in this age class(t = 0.67, P = 0.53). For adult males, distancesbetween successivelocationsaveraged 1.4 + 0.4 km late in the seasonand 1.3 + 0.2 km early in the season,and were not significantlydifferent (t = 0.26, P = 0.79). Adult male home rangesused late in the season(2.4 + 1.3km•) were significantlylarger than home rangesusedearly in the season(0.6 + 0.1 • '• 100- • ---- -•- SY 75- u_ 50z • 25- km•; t = 3.56, P = 0.01). Discussion.--Our findingswere consistentwith predictions of the dominance hypothesis:late-winter home rangesof ATY maleswere closerto spring display groundsthan were rangesof youngermales.In addition, larger SY males, which presumablyare dominantover smallerSY males,alsodispersedshorter distanceswithin this age group. Becausesuitable habitatsfor nestingare limited in our study areaand prenestingdispersalof femalesis influencedby nesthabitat searching(Badyaev1994,1995),malesbenefit 0 • 15 25 •5 45 PERGENT 55 OF 65 75 85 95 OBSERVATIONS Fig. 1. Patternsof displayrange use in SY (n = 6) and adult (TY and older; n = 8) male Wild T•tkeys. SE showRfor eve• [20 + 10•] petceRtageof obser- vation for SY males,and for eve• [25 + 10•] percentageof obse•ation for adult males. 242 ShortCommunications andCommentaries most predictability in display behavior when near nestinggrounds.Male fidelity to displayingsitescontributesto maintaining safedistancesbetweenfemale nestsand male display sites,ensuringthat maleswill not follow females to their nesting areas, thereby making them more conspicuousto predators(Bergerud 1988). Wild Turkey malesof all examinedage groupsincreased their movements later in the season. The ob- served pattern is consistentwith our prediction and could result from a decline in availability of receptive females and changesin the previously established hierarchy in breeding areasas a result of human dis- turbance(e.g. hunting). In addition, more areasbecamesuitablefor nestinglater in the season(Badyaev 1995) and, therefore, female distribution was not so restrictedas it was early in the season. Acknowledgments.--We are grateful to D. Frick, D. Hasenbeck,A. Hodgson,T. Lane, and K. Teter for help with the fieldwork. We thank F. C. Jamesand J. E. Johnson for helpful discussion.This paper was significantlyimproved by commentsfrom A. T. Bergerud, G. D. Schnell, M. A. Schroeder,and an anonymousreviewer. The supportof the ArkansasGame and Fish Commissionand the University of Arkansas is gratefully acknowledged. [Auk,Vol. 113 and dispersal in birds and mammals. Anim. Behav. 28:1140-1162. HEALY,W. M. 1992. Behavior. Pages46-65 in The Wild Turkey: Biology and management(J. G. Dickson, Ed.). Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. HOFFMAN, R.W. 1991. Spring movements,roosting activities,and home-rangecharacteristics of male Merriam's Wild Turkey. Southwest.Nat. 36:332337. JOHNSON, C.N. 1986. Sex-biasedphilopatry and dispersalin mammals.Oecologia69:626-627. JOHNSON,M. L., AND M. S. GAINES. 1990. Evolution of dispersal:Theoretical models and empirical testsusing birds and mammals.Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 21:449-480. KELLY,G. 1975. Indexes for aging easternturkeys. Proc.Natl. Wild Turkey Sympos.3:205-209. KENWARD, R. 1990. RangesIV. Softwarefor analyzing animal locationdata. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology,Wareham,United Kindom. PART,T. 1994. Male philopatry confersa mating advantagein the migratoryCollaredFlycatcher, Ficedula albicollis. Anim. Behav. 48:401-409. PHILLIPS,J. B. 1990. Lek behaviour in birds: Do dis- playing malesreducenestpredation?Anim. Behav. 39:555-565. LITERATURE CITED SCHROEDER, M. A., AND G. C. WHITE. 1993. Dispersion of Greater Prairie Chicken nests in relation to lek location:Evaluationof the hot-spothyBADYAEV, A.V. 1994. Springand breedingdispersal pothesisof lek evolution. Behav.Ecol.4:266-270. in an Arkansas population of Wild Turkeys: Causesand consequences for reproductiveper- STEFFEN,D. E., C. COUvlLLION, AND G. A. HURST. 1990. formance. M.Sc. thesis, Univ. Arkansas,FayetteAge determinationof easternWild Turkey gobville, Arkansas. BADYAEV,g.V. 1995. Nest habitat selection and nest successof eastern Wild Turkey in the Arkansas Ozark Highlands. Condor 97:221-232. BADYAEV,A. V., W. J. ETGES,AND T. E. MARTIN. 1996. Ecologicaland behavioralcorrelatesof variation in seasonalhome rangesof Wild Turkeys in the ArkansasOzarks.J. Wildl. Manage.60 (in press). BERGERUD, A. T. 1988. Mating systemsin grouse. Pages439-472 in Adaptive strategiesand population ecologyof northern grouse(A. T. Bergerud and M. W. Gratson, Eds.).Univ. Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. BRADBURY, J. W., AND R. M. GInSON. 1983. Leks and mate choice.Pages109-138 in Mate choice(P. P. G. Bateson,Ed.). Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge. GREENWOOD, P.J. 1980. Mating systems,philopatry biers. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 18:119-124. SWIHART, R. K., ANDN. A. SLADE.1985. Testingfor independence of observationsin animal move- ments.Ecology66:1176-1184. TSUJI,L. J. S., D. R. KOZLOVICH,M. B. SOKOLOWSICI, ANDR. I. C. HANSELL.1994. Relationshipof body size of male Sharp-tailed Grouse to location of individual territories on leks. Wilson Bull. 106: 329-337. WEATHERHEAD, P. J.,AND R. J. ROBERTSON. 1977. Har- em size, territory quality, and reproductivesuccess in the Red-winged Blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus). Can. J. Zool. 55:1261-1267. WRIGHT, S. 1946. Isolationby distanceunder diverse systemsof mating. Genetics31:39-59. Received 5 December 1994,accepted 26 June1995.