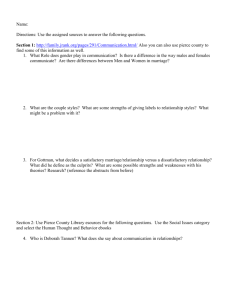

THE UNCERTAIN ENFORCEABILITY OF PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENTS: WHY THE “EXTREME” APPROACH IN

advertisement