B

advertisement

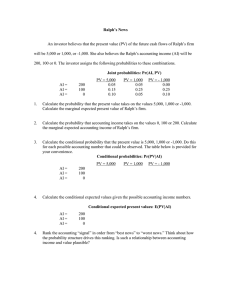

Appendix B. A Few Days with Ralph at the Desert Range By Richard J. Klade B efore I first worked in a research organization in 1968 my perception of scientists probably mirrored the general public view. Scientists were deadly serious people who wore white coats and spent endless hours studying mysterious phenomena. They were important people, but humorless and sort of dull. The “mad scientist” or “absent-minded professor” types were entertaining, but most people thought they existed only in the movies or as characters in comic books; they didn’t represent reality. So far, I’ve yet to meet a mad scientist. But I have encountered a number of researchers who might be considered real characters, unusual people who were perhaps a bit eccentric. Most of them were delightful. Not the least of these characters was Ralph Holmgren. Ralph worked for many years at the Desert Experimental Range, a remote outpost some 300 miles southwest of Ogden. The range is 48 miles west of the nearest community, Milford, Utah. Research there focused on the effects of grazing on dry-land vegetation, which covers millions of acres in the Interior West. Before my opportunity to visit him at his desert home in 1976, Holmgren was known to me largely by reputation. Coworkers said Ralph liked the Desert Range so much that he disliked leaving the place and even spent his vacation time there when he took annual leave. He often was referred to as “the old sheepherder.” One rumor was that Ralph had a pet antelope at the range. He was said to be a genial man, somewhat shy, whose habits were a bit unusual. The unusual part was confirmed on one occasion when I encountered him checking into the Ramada Inn in Ogden before attending a meeting at Station 250– Headquarters. Ralph’s luggage consisted of two shopping bags. The man carrying his belongings in bags was of average size, deeply tanned from hours under the desert sun, and had a twinkle in his eye. Dispatched to the Desert—Any formal records of my visit to the Desert Range are long gone, and trying to recall events that happened nearly 30 years ago is a chancy business. However, one thing is certain. I never was sure why I was sent there. Either Station Director Roger Bay or Assistant Director Jim Blaisdell told me to go. The mission was something vague about “helping Holmgren get some writing done,” and also “working with him” on a visit by Bureau of Land Management (BLM) range managers. “Work with him” is an assignment often made by Forest Service managers when they are keeping a commitment to send help, but really don’t know what the problem is. Like a good soldier, I went. My visit was in late June of 1976; the weather was dry and it was hot. The trip began very early in the morning to allow for a brief lunch stop in Milford and get me to the destination early enough in the afternoon to help Ralph that day with whatever I was supposed to help him with. As I progressed down State highways on the 6-hour drive from Ogden the temperatures got hotter, signs of human habitation were fewer, and vegetation became more and more sparse. People who are not impressed with the beauties of desert shrubbery and an empty landscape might call the area encompassing the Desert Range “desolate.” I won’t go that far, but must admit the surroundings are somewhat less than lush. The entry road passed between two stone pillars. A buzzard was perched atop one of the pillars when I went through. That turned out to be of no significance, much to my relief. The stone pillars at the Desert Range entry were impressive, with or without a roosting buzzard. Incidentally, I learned later that the pillars were made of Warm Point Quartzite, a rock found near the Desert Range. They were built by CCC men during the 1930s, as were the buildings, fences, and roads. Working With Ralph—A young man who was a student at Brigham Young University (BYU) employed for the summer directed me to the building where Holmgren was to be found. He was seated at a desk in a second-floor loft, with pencil in hand, ruefully contemplating a stack of papers that looked like a publication manuscript. Aha, we were going to work on the first part of my assistance assignment. Ralph’s answers to a few discrete (I hoped) questions about problems he might be having with the writing didn’t pinpoint much of anything. If he had a problem, it probably was the one faced by most authors at one time or another—reluctance to apply one end of the anatomy to a chair and start the other end concentrating on the job at hand. We chatted for a while about writing in general, and I pointed out several times that I was willing to help with anything he wanted. “Well,” said Ralph, “we’ll have 25 BLM guys coming in tomorrow. A few are from the Nevada State Office, but most are from Districts in Utah and Nevada. We’ll spend the whole next day on a tour of our study plots. Some of the Districts are pretty far away; so a few are staying over two nights. We need to get things ready.” My first (and actually only) assistance task was moving mattresses. Ralph, the BYU student, Range Technician John Kinney, and I carried them from a pile on the second floor of a storage building to various other buildings in the Desert Range complex. There were only 24. When concern was expressed about how 25 BLM guests, plus me, were going to sleep on 24 narrow mattresses, Ralph just shrugged and said, “Oh, things like that always work out.” He then announced, “We need to get some provisions. Come on, we’ll take a ride over to the store.” Although several government vehicles were parked in the complex, we got into Holmgren’s personal car. My recollection is it was a brand-new, white, Chevrolet sedan. With all the out was easier than getting in. The fence windows rolled down, we took off had some 2-by-4 cross braces on the toward the west at a pretty fast clip. It inside that made the climb up easy. was mid-afternoon, and no doubt the We finished the return trip to the temperature was in the 100s. We drove Desert Range without incident. Passing for quite a while, finally stopping at a through the area where vehicles were dilapidated general store. A rough lookparked, I expressed surprise that Ralph ing guy attired in worn out jeans and a would take his new personal car (now dirty underwear shirt was the only clerk. thoroughly coated with dust) instead of He was a big fellow, and I envisioned a government rig. “None of them have talking him into hauling the boxes of been running for a while,” Ralph said. food we were about to buy out to the car. “Our guys are taking parts out of two of By then, I was almost as sweaty as he them to see if they can get that one over looked, and there was no way I wanted there going.” to do anything physical. I then asked if air conditioning wasn’t We walked around in the store for a available when Ralph bought his Chevy. while. Ralph bought two-dozen cookies Gesturing toward a small pile of hoses, and a six-pack of beer. We left. tubes, and miscellaneous metal parts The Journey Back—At what near one of the disabled government seemed like about the midpoint in the vehicles, he said, “Oh, it came with it. drive back to the Desert Range, Ralph I’ve never liked it in my cars—took it asked if I was interested in historic sites. out right away.” When I said I certainly was, he said, The next question concerned the pet “Good, there’s a ranch just ahead that antelope. “She should be around about has a family graveyard that dates back to this time,” Ralph said, “We’ll run out early settlement days around here. We’ll and see her.” We drove a short distance drop in on them and I’ll show it to you.” past the buildings and parked in an We veered off the highway to the area facing a gentle hill. “There she right onto a dirt road, drove about a is,” Ralph said. Sure enough, a young half mile, and pulled up in front of a pronghorn stood part way up the rise. large ranch house. No one was home. Ralph called out, “Annie, come “That’s OK,” Ralph said. “They won’t here.” The antelope didn’t move. He mind if we just go ahead and look at the cupped his hands and yelled, “Come headstones.” here, Annie.” Nothing happened. He Well, they apparently did mind if jumped up on the hood of the Chevy people tramped through their graveyard. and yelled louder, “Annnneeeee.” There A “chicken wire” fence about nine feet high surrounded the plot. A formidable padlock secured the gate. It’s a guess, but Holmgren was probably about 55 years old. I was in my 30s and in reasonably good shape, I thought. He went up and over that fence in a flash. I struggled up, and with Ralph tugging at me from a perch on the inside, Desert Range Superintendent John Kinney showing a more or less fell into small visitor how Annie responded to a sugar cookie treat. the graveyard. The The little girl was a member of a family driving by on the several dozen tombnearby highway. They spotted the antelope and Kinney, stones were, indeed, stopped, and the daughter got a first-hand introduction to wildlife. interesting. Getting –251 was no movement on the hillside. Ralph turned to me and said, “Heck, that’s not Annie.” For the benefit of doubters, and I was one, there really was a pet antelope named Annie at the Desert Range. John Kinney, who served at the range for nine years, had a picture of Annie on the wall of his office in Boise in 2004. He says she was quite tame and liked to nibble on sugar cookies provided by the staff. It was starting to get dark and we headed for the kitchen. The BYU student, Kinney, and a fourth resident, Don Beale, a Utah Division of Wildlife Resources researcher, were there. Beale was doing a study of antelope. He also was the cook. After dinner, Ralph took me to another room in the dwelling and showed me a bed he said I was welcome to use during my stay. He then went off somewhere, and wasn’t seen again until the next morning. I went back to help the kitchen crew clean up and see if they would comment on a few of the day’s minor mysteries. They enlightened me. Kinney and the student said it was really good luck that Beale was there to cook. They said Ralph hated to cook, and if nobody was around to do that chore he lived mainly on oatmeal cookies. The BLM guests were bringing their own grub, so the “provisions” we had gone to get were just Ralph’s personal supplies. Ralph had given me his bed. That gift concerned me in view of the impending mattress shortage. Where was he going to sleep? The crew said it was no problem at all. “He’ll probably just stay up all night reading. He does that a lot.” The Guests Arrive—Breakfast was just after sunup. Beale laid out a good spread and the five of us consumed it all with gusto. As we ate, the “regulars” had a lively discussion of whether or not it was going to rain that day. That was interesting, because average annual precipitation at the Desert Range compound is about six inches, and half of that is snow in winter months. Rainy summer days probably are causes for great celebration. When the weather topic was exhausted, I asked Ralph if he had worked in other places. “I worked up in Idaho for a while,” he said, “but the trees made me nervous.” 252– The BLM managers arrived at intervals throughout the day. Ralph greeted them and the student and Kinney showed them to their mattresses. The guests took over the kitchen and made lunch. We did the neighborly thing and helped them eat it. They were good cooks and we no longer had a kitchen, so we also helped them Ralph Holmgren explained how to apply findings from reconsume the dinner search at the Desert Range to BLM range managers during they made that night. the field day, June 22, 1976. At least some of us did; Ralph wasn’t seen at lunch or dinner. In mid-afternoon, one of the Utah ways, most by sheep, a few by cattle. District guests hurried up to Ralph and Within the pastures are fenced exclosaid he was terribly sorry but he just got sures. Inside them the vegetation has a radio message about a bad accident been allowed to grow with no disturback in his unit. He had to leave right bance by large animals. So researchers away to take care of the crisis, and have been able to compare the effects on couldn’t possibly return for the field plants of various grazing systems, or no day. After he left, Ralph glanced at me grazing, and also study plant succession and said, “Well, I guess that makes over many years. twenty-four.” As our group started walking toward A Day on the Range—The next day the first pasture on the agenda, a young we temporarily reoccupied the kitchen manager pointed to a shrub, and said for another breakfast at daybreak. Once something like, “Oh, there’s ______, again, the discussion topic was the _____” (He spouted a Latin scientific chance of rain interfering with the day’s name). Ralph stopped the group. He activities. The BLM men started appear- said, “No, that’s _______, ______, ing, we left, and they made breakfast _______, ______.” (He identified the and cleaned up the kitchen. That took a plant by the correct scientific and comwhile, but it was still pretty early when mon names). Holmgren then reeled off all the guests were assembled outside about a dozen scientific and common waiting for business to get under way. names of plants that grow at the Desert The field day got off to a somewhat Range, pointing out several that were rocky start. Ralph ambled out to face the in our immediate vicinity. For each, he group. He was wearing wrinkled work added information on plant associations, pants, well-worn hunting boots, a floppy forage values, and growth characterisbucket hat, and a patterned shirt. The tics. Anyone who had been unimpressed shirttail was hanging out. He launched with our field day leader was converted into a rambling, somewhat disjointed right then and there. welcome and orientation talk. The Respect turned to awe throughout a BLM managers fidgeted around a little very long day as Ralph expounded on and seemed unimpressed. One near me the meaning of what we were seeing at was overheard to mutter, “This is our exclosure after exclosure. He gave the expert?” results of studies on seasons of use, rotaThe Desert Range is divided into tion systems, watering techniques, and some three dozen study pastures that herding and handling animals, sprinkling have been grazed in various controlled in management recommendations. The managers hung on his every word. There obviously was very little Holmgren didn’t know about the results of 40 years of research at the Desert Range. And he described things in terms the BLM men obviously understood. Number, please—Most of the guests drove off for home after dinner that night. After the stragglers left in the morning, our little group settled in for a relatively late, and leisurely, breakfast. Of course, an argument soon erupted about the chances for rain that day. Well, enough was enough. I finally interrupted and said something like, “You guys are just pulling my leg. There’s about as much chance of rain today as there is it will snow.” Soon thereafter it rained for two or three minutes. Ralph just smiled, touched my arm, and pointed at the raindrops on the kitchen window. Ralph went off somewhere and while we were doing the dishes the conversation turned to the telephone on the kitchen wall. It was the type now found only in museums. I learned it was on a party line, and anybody could listen in on conversations. The Forest Service built and maintained the line, so among the duties of John Kinney was acting as manager of the local phone company. It wasn’t a very big company; it served the Desert Range and one other customer, a ranch. The line ran 48 miles to a school in Milford. Signals were rings like “two shorts and a long.” During my visits to the kitchen, whenever one signal rang no one answered. My guess was the calls were to the ranch house where we had inspected the family graveyard. But it seemed strange that everyone would be gone for several days from a working ranch that looked like a big operation. That wasn’t it, the breakfast crew said. “That’s our ring. Ralph hardly ever answers it. He says it’s usually just somebody in Provo or Ogden wanting some fool thing or other.” Spending a few days at the Desert Range was not one of the major events in my life, but it comes to mind fairly often. Whenever I have occasion to munch on an oatmeal cookie it reminds me of Ralph Holmgren—competent scientist, good host, gentleman…and a real character. –253