INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1

advertisement

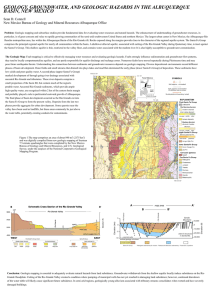

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION For more than 450 years the ecosystems of the Middle Rio Grande Basin have evolved dynamically with the interrelated vagaries of climate, land forms, soils, fauna, flora, and most importantly, human activities. Various land use practices have caused an array of environmental problems. Activities such as grazing, irrigation farming, logging, and constructing flood control features, combined with climatic fluctuations, have produced changes in stream flow-morphology, groundwater levels, topsoils, biotic communities, and individual species. Indigenous human populations have, in turn, been impacted by modifications in these resources. This report examines these processes, impacts, and changes in depth. SCOPE OF THE PROJECT This study of the environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin, and to a lesser degree the Upper Basin (Fig. 1), was begun on June 1, 1994, and continued until February 15, 1996. This project is part of a multidisciplinary research program called “Ecology, Diversity, and Sustainability of Soil, Plant, Animal and Human Resources of the Rio Grande Basin” and was initiated by the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Albuquerque, in 1994. The larger 5-year study is focused on the retrieval, synthesis, and interpretation of extant and new data on the Middle Basin to better understand ecological processes, including not only the interrelationship of physical and biological components of ecosystems but also the human element. As the dominant force and agent of change, various human groups or eco-cultures1 have impacted all Basin ecosystems for more than 10,000 years (Stuart 1986: a–c). To address these interrelationships over time, the study team, under the direction of Deborah M. Finch, identified four areas of research: (1) responses of upland ecosystem components to “natural” as well as human perturbations and how these responses have affected or will affect the dynamics, stability, and productivity of these ecosystems; (2) interrelationships of lowland riparian and upland ecosystems of the past and present; (3) species responses to barriers in dispersal, migration, and reproduction along the Rio Grande and selected tributaries and identification of those plants or animals and their needs for sustainable management; and (4) environmental history of the Basin to better understand the kind and extent of human inter- USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–5. 1998 actions with ecosystems and the sustainability of such traditional eco-cultural activities within regional ecosystems. The focus and context of these research areas are interrelated and grounded in environmental history as they relate to human uses, impacts, and changes within a context of climate, fire, and other ecosystem dynamics. Further, environmental changes generated by various groups sometimes resulted in modification of their world views and economic systems. Without a better understanding of these historical processes and their end results, bioremediation and sustainability of Basin ecosystems, including traditional lifeways, will be difficult if not impossible to accomplish. This report on the environmental history of the Middle and Upper Rio Grande basins2 provides data pertinent to all four research areas. The Middle Basin includes the Rio Grande from Bandelier National Monument to the upper end of Elephant Butte Reservoir and seven major tributaries—Santa Fe River, Galisteo Creek, Jemez River, Las Huertas Creek, Rio Puerco, Rio San Jose, and Rio Salado. Within this region are three national forests—Carson, Santa Fe, and Cibola—in which lie the southern Sangre de Cristo, Jemez, Sandia, part of the Zuni and Datil, Manzano, Ladron, Los Pinos, Magdalena, and San Mateo mountains (Fig. 2). The Upper Basin extends northward embracing the Espanola Basin, the Rio Chama, the Rio Grande Gorge, the uplands of the Carson National Forest, and the uppermost watershed of the river in southern Colorado (Figs. 1 and 3). This latter area includes the San Luis Basin, part of the northern Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and the eastern extension of the San Juan Mountains in the Rio Grande National Forest. The Upper Basin is included in this study for several reasons. The Middle Valley ecosystem is first and foremost driven by water, and much of this resource comes 1 For these distinct groups interacting with and changing their environment, the term eco-cultures will be used in this report to reflect their ecological use of, impact on, and interaction with the resources and ecology of the area. Also, archeological remains of these groups will be referred to as eco-cultural resources. This term precludes the use of more cumbersome, and misleading, compound descriptors such as “cultures and environments” or “humans and nature.” 2 Collectively, these two basins will be referred to as the “study region.” Use of the term “region” refers to the study region and adjacent areas. 1 Figure 1—Study region. 2 USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–5. 1998 Figure 2—Middle Rio Grande Basin. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–5. 1998 3 Figure 3—Upper Rio Grande Basin. 4 USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–5. 1998 from the Upper Rio Grande and tributaries above the north boundary of the Middle Basin (Figs. 1 and 3). Floodwaters generated in the Upper Basin affected virtually all components of the middle one. Upper Basin droughts clearly affected the Middle Valley ecosystem in other ways. Further, some plant communities and animal populations also extend across this boundary, and various human groups moved from one basin to the other over time, impacting both basins with their activities. Sustainability of ecosystems, and their significant human component, clearly lies in studying and managing both basins as one. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY Environmental history has been recognized only recently by the academic community as a viable and needed approach to better understanding human history by placing it in an environmental context. However, decades before this, several individuals, such as Aldo Leopold, James Malin, and Walter Prescott Webb, were developing and applying environmental history methodology and theory to understanding and describing human groups and their interrelationships with ecosystems. Although Leopold called for “an ecological interpretation of history” more than 50 years ago, environmental history was not a recognized academic discipline until the 1970s, following the dynamic and influential environmental movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s (Worster 1993: 2). The American Society of Environmental History was formed in the bicentennial year of 1976. Since then, this new field of study has embraced related fields such as climate history, fire history, landscape ecology, forest history, agricultural history, anthropology, ethnohistory, and history of conservation and science. Some specific topics addressed by environmental historians, and discussed in this study, include historic floods and droughts, hydrology and geomorphology of streams, the “Columbian exchange,” environmental views of groups in a given area or region, environmental impact and change, and evolution of conservation and scientific research (Merchant 1993: vii–ix). Aldo Leopold has been called the “father of wildlife management,” and his prolific writings have significantly influenced the philosophy and methodology of environmental sciences. Leopold’s published books, such as A Sand County Almanac (1944), and papers have also helped shape the view of many contemporary ecologists and environmental historians, such as Donald Worster of the University of Kansas. This influence is reflected in Worster’s (1993: 4) definition of his own field of study: “[Environmental history] deals with the role and place of nature in human life. . . .” and “Its goal is to deepen our understanding of how humans have been affected by their natural environment through time, and conversely and perhaps more importantly in view of the present global predicament, how they have affected that environment USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–5. 1998 and with what results.” Importantly, this discipline has not only expanded the view and “data base” for historians but has also provided pertinent data for biological scientists and resource managers to use in developing a more comprehensive approach to bioremediation, reconstruction of ecosystems, and determination of sustainability. The ecosystem, or watershed, approach to study of areas or regions used by ecologists for some time is emulated by the bioregional approach that some environmental historians have used. This focus on a definable abiotic-biotic region in which various groups have employed distinctive adaptive and exploitive strategies was discussed by Dan Flores (1994: 8): . . . [A] given bioregion and its resources offer a range of possibilities, from which a given human culture makes economic and lifeway choices based upon the culture’s technological ability and its ideological vision of how the landscape ought to be used and shaped to meet its definition of a good life. The Middle and Upper Rio Grande basins, with a long history of human occupation, have been studied by archeologists and historians for more than a century. The region’s prehistory and history, reconstructed from an array of physical and documentary evidence possibly as comprehensive and detailed as that of any region in the United States, lend themselves to the bioregional approach. The distribution of the protohistoric Pueblo groups was mainly limited to the Middle and Upper Rio Grande basins; the Zuni and Hopi Pueblos were the exceptions. Subsequent Spanish settlement was confined to the basins as well until the early 1800s. The Spanish also recognized the environmental distinction between the Upper and Lower basins, which they named the Rio Arriba and Rio Abajo, respectively, for purposes of administration. Further, early Anglo settlers almost exclusively occupied these two ecological units. Also found here are descendants of the two earlier eco-cultures, Native American and Hispanic, who still practice traditional lifeways to some degree, so there is a continuing historic record today. In general, this study focuses on identifying and interpreting the roles of various human groups in affecting Basin ecosystems and their responses to the environmental changes that they and “nature” have produced. Although it was known that human groups had, over time, shaped all regional ecosystems from the Rio Grande to the tundra of the highest peaks, the processes of these transformations were poorly understood. This study examines in detail the interrelationships of various eco-cultures with their Middle Basin environments, with a special focus on how groups have viewed and exploited their environments. In addition, the general role and relation- 5 ship of politics, economic institutions, and social organizations to resource exploitation and its resulting impacts on the environment are clarified. Finally, a number of specific environmental changes and their spatial and temporal occurrence, nature, and impacts were identified and are discussed. Because an environmental history of this spatial and temporal magnitude has never been attempted in New Mexico, the first priority was to review and integrate the readily available, pertinent data on human prehistory (late) and history with data from the physical and biological sciences. Important sources of this type of information were published works on local environmental histories within the study region, such as Man and Resources in the Middle Rio Grande Valley by Harper et al. (1943) and Enchantment and Exploitation (Sangre Cristo Mountains) by deBuys (1985). Publications dealing totally or in part with the historical use of specific environmental components, such as the Climate of New Mexico by Tuan et al. (1973), Water in New Mexico by Clark (1987), Birds of New Mexico by Ligon (1961), and Fishes of New Mexico by Sublette et al. (1990), were also helpful in providing general context, as well as more specific data on topics of special interest. Recent comprehensive studies on the ecology of the study region, such as the Middle Rio Grande Biological Survey by Ohmart and Hink (1984) and the Middle Rio Grande Ecosystem: Bosque Biological Management Plan by Crawford et al. (1993), provided a sound basis for understanding the interrelationships of the river and the various biotic components of the Middle Basin. Most of the allocated research and analysis time was devoted to review of these and other pertinent published books, reports, papers, and documents. Unpublished manuscripts, maps, and photographs were consulted as time permitted. Data from selected oral interviews conducted by me and other researchers were also reviewed. There is a huge body of archival material in various state and regional depositories that was not researched during this project owing to time constraints but should be included in future regional or local environmental history projects. Early in the project, 10 research problems requiring environmental history data were identified for inclusion in the study: (1) effects of climatic phenomena, such as droughts, on human views of and responses to the environment; (2) effects of human activities on changing local, regional, or global climatic components and regimes; (3) effects of the temporal occurrence and magnitude of flooding on historic land use activities; (4) effects of grazing on different ecosystem components such as plant communities; (5) effects of erosion on fauna, flora, and other 6 components; (6) effects of various water control structures on riparian fauna and flora; (7) effects of fragmentation of the Rio Grande bosque on riparian ecosystems; (8) effects of introduced plants and animals on ecosystems; (9) effects of past resource management by various agencies on these same ecosystems and their traditional resident eco-cultures; and (10) effects of environmental impacts on human responses, specifically attitudes, to these perturbations. These 10 problems guided the research presented in this report. Four spatial-temporal models of impact and change in the Middle Rio Grande Valley were also developed for “testing” during the study. ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT Chapters 2 through 6 describe and reconstruct the history of occupation and use of the study region by various human groups, the historic environmental conditions in the basins, and the impact on and modification of abiotic and biotic components of Middle Rio Grande ecosystems by natural and human events over the last 455 years. These chapters include historic and recent climates (Chapter 2), human settlement and land use (Chapter 3), historical descriptions and reconstruction (Chapter 4), impacts and changes (Chapter 5), and the origin and development of a conservation ethic and related land management agencies and organizations (Chapter 6). A chronology of pertinent events is provided at the end of each of these chapters. The final chapter (7) is a synthesis of the information presented in the previous chapters, with conclusions and considerations for using the data from this report in future research studies and management programs. BENEFICIARIES OF RESEARCH In addition to potential data uses by various public resource management agency personnel at all levels, this study should be useful to a myriad of other Basin communities and organizations—Pueblos, Hispanic land grant associations, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, universities and schools, environmental groups, and private contractors and individuals involved in Middle Rio Grande Basin research. Potential uses include evaluating current resource use and management, planning for bioremediation of environmental problems at specific locales or areas, evaluating sustainability of past and current land use practices, locating field trip and study area sites for schools, and identifying, and hopefully resolving, critical environmental issues. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–5. 1998