Evolution of Bargaining Positions of Women in Russian Families

advertisement

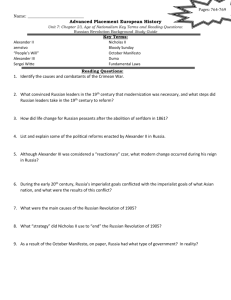

Evolution of Bargaining Positions of Women in Russian Families∗ Natalya Y. Shelkova Assistant Professor of Economics Department of Economics Guilford College 5800 W.Friendly Avenue Greensboro, NC 27410, USA tel.: 1-336-316-2293 fax: 1-336-336-316-2467 shelkovany@guilford.edu April 15, 2014 Abstract In this paper uses data from Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (RLMS-HSE) to investigation the effects changing socioeconomic environment have had on the relative bargaining positions of women in Russian families. To understand ‘the big picture’ I first examine major trends in work and family life of Russian women, namely, trends in labor force participation, college education, occupational choice, marriage and divorce rates, fertility, use of contraceptives and abortion rates. Then a closer look is given to the period of 2002-2008, estimating a regression model that allows to infer whether exogenous social changes affected Russian women’s bargaining strength within the family. Namely, I look into how family expenditures on children changed relative to family’s spending on alcohol and tobacco throughout this period, testing the hypothesis that a stronger women’s position increases spending on children, while relative weakening of men’s position reduces spending on alcohol and tobacco. The findings suggest that the previously recorded negative trend which disadvantaged Russian women in 1990s and early 2000s had been reversed in mid-2000s, implying that the new economic and social order finally started to benefit women. Keywords: women, labor force, family bargaining, transitional economies JEL classification codes: J12, J16, P2 ∗ Work in progress - please do not quote. 1 1 Introduction Russian women, praised by poets for their strength and beauty, have long held an unequal position in the family and Russian society. The Soviet government, which promoted equality at work and in education, did not achieve equality in the family life for Russian women. Women, historically very well-educated and strongly attached to the labor force, have led family life that remained largely traditional. Soviet society expected women to be good mothers and wives and have successful careers, and women were trying to play both roles, striving for perfection in both areas. Most Soviet families had strict division of labor, similar to traditional societies where women stayed home. Married women carried out disproportionately large share of house work and child care. Cooking, cleaning, shopping, making and repairing clothes for family members were on the shoulders of women. Part of my motivation for this project came from reading literature on women experiences in the U.S. in the second half of the 20th century, their empowerment. I was wondering whether Russian women have followed the same or somewhat similar historical route. However, experiences of Russian and American women in the second half of the 20th century were drastically different. Post-WWII American economy was strong, well-paid men were supporting entire families. Some women chose to work, encouraged by growth of women-friendly occupations, equalizing educational opportunities, the Pill and the growth in household technology (Goldin 2006). These external to family developments made women’s position in American family stronger. Soviet society, on the other hand, in ruins after the second world war, lost a colossal number of prime age men. Women, who joined the labor force during the war, continued to be employed. At the same time, the odds of finding a husband were not in their favor. Fierce competition in the marriage markets tipped the family balance of power, made married women’s share of family resources unequal with men, even though they continued to work. As the demographic situation improved in the 1960s, as new cohorts of men were born and entered the marriage markets, women’s position in the family did not undergo a significant change. Chronic shortages of consumer products coupled with low pay forced Soviet families to engage in significant home production. Married women were sewing, knitting, gardening, making home preserves on a large ‘industrial’ scale, not as a hobby, but as a necessary condition for survival. Substantial home production without much household technology required ‘strong hands’, and benefited immensely from presence of men, as services were also not yet available in non-existing markets of the Soviet economy. The collapse of the Soviet Union brought about many changes. Changing structure of the Russian economy have given a number of choices to women. New labor laws allowed them to choose whether to work, – before paid employment was nearly mandatory. Opening of borders made consumer goods, household technology, as well as western contraceptives widely available. As abortion was not longer a major instrument for birth control, women gained greater flexibility in family planning and better health. The new market economy did not only bring an abundance of consumer goods, including most up-to-date household appliances, but also led to emergence of a variety of markets for services, which could substitute men’s hands when it came to keeping the household. In this paper I examine data from Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (RLMS-HSE) with the purpose of investigation of the effects that changing socioeconomic environment has on the relative bargaining positions of women in Russian families. In order to understand ‘the big picture’, I first examine major trends in work and family life of Russian women, namely, trends in labor force participation, college education, occupational choice, marriage and divorce rates, fertility, 2 use of contraceptives and abortion rates. Then I take a closer look into a period of 2002-2008, estimating a regression model that allows to infer whether exogenous social changes (including the “Maternal capital” law of 2007) affected Russian women’s bargaining strength in the family. Namely, I look into how family expenditures on children changed relative to family’s spending on alcohol and tobacco throughout the period, testing the hypothesis that stronger women’s positions increased spending on children, while relative weakening of men’s position reduced spending on alcohol and tobacco. Prior studies of bargaining strength of Russian women (Laroix & Radtchenko, 2011; Kalugina, Sofer, & Radtchenko, 2009), by analyzing the data from 1990s to early 2000s concluded that women’s positions in the Russian family had been weakened during the ‘transition’ and associated with it economic calamities. My preliminary findings suggest that the negative trend might had been reversed in mid-2000s, implying that women could have finally adapted to the new economic and social order. 2 Data In this paper I use data from Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (RLMS-HSE), “is a series of nationally representative surveys designed to monitor the effects of Russian reforms on the health and economic welfare of households and individuals in the Russian Federation”1 . The survey is a detailed study of Russian family, adults and children within the family, as well as communities. It started in 1992, the first year of drastic economic reforms in Russia known as ‘liberalization’. In this innovative for Russia survey, respondents are asked many ‘new’ questions that were never asked before: “For ideological reasons, social research was severely restricted until recently. Many powerful local authorities prohibited surveys of the adult population in their regions out of fear that surveys would bring problems to the attention of their superiors.”(RLMS-HSE). Since 1992 the data has been collected every year (with exception of 1997 and 1999), generally during the last quarter of the year. The sampling design of the survey has changed in 1994, which started Phase II, and survey administrators suggest to primarily use this later data, which I do in this paper. Each annual sample represented approximately 4,000 households till 2010, when it was increased to 6,000. The survey is highly representative of the population’s composition by gender, education, geographic location, urbanization level. 3 Statistical Overview Examination of averages for women and married women in 1995-2011 confirms that Russian women remain strongly attached to the labor force, perhaps due to significant differences in wages between men and women, and increasingly invest in higher education. Fertility is on the rise after the demographic trough of the 1990s, and women are more likely now to use contraceptives, as opposed to abortion, as a mean of the birth control. Younger women marry later in life, and it appears that women divorce after their most fertile years are over. Figure 1 illustrates continued strong attachment to the labor force by Russian women. According to RLMS, in 2011 (most recent round) 87% of women of working age (16 to 55 years old) were in the labor force, versus 90% of men. In comparison, in 2013 labor force participation of American 1 Russia Longitudinal Monitoring survey, “RLMS-HSE”, conducted by the National Research University Higher School of Economics and ZAO “Demoscope” together with Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Institute of Sociology RAS. (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/rlms-hse) 3 Figure 1: Labor Force Participation women aged 35-44 (most economically active) had participation rate of 82.7%, and average participation of women 16 years and older was 64.1%. Both for Russian men and women, labor force participation rates appear to be countercyclical, with participation rates rising during economic downturns. As you can see from the Figure 2, women of all age groups are moving away from elementary and craft occupations, towards service and sales jobs (especially true for younger women) an professional work. This reflects a somewhat similar transformation that American women experienced in the 20th century, when markets become more accommodating to women’s preferences, abilities and schedules, when it came to market work. Although Russia has long had relatively plentiful choices of women-friendly work, these recent trends still point out expanding career options for women. Greater accessibility of higher education (due to emerging educational markets), delayed marriage, and overall demands of a changing economic structure (declining manufacturing and expanding services) may explain why more women choose to obtain college degrees (Figure 3). According to RLMS, in 1995 15% of women age 16 and older were college-educated, about the same as men. Recent developments in Russia pushed relatively more women than men to obtain college degrees. This statistic grew to 25% in 2011 for women, and only to 20% for men. Married persons in Russia, and more so women, are more likely to be college educated now than they were in 1995. Percentage of married persons with college diplomas is greater than population’s average, and is growing faster (Figure 3). In 1995 about 18% of married men and women were college educated; in 2011 – 29% of women, in contrast with 23% of men. The marriages that are forming, appear to be of better quality. In more marriages both spouses are college educated (Figure 4). This can explain why the pay gap between spouses is narrowing. Overall nowadays fewer women are married (see Figure 5), and average age of married women is higher than it was in the beginning of the investigated period. However, the declining trend was broken in 2009, which could be due to the effect of the new law passed in 2007 that promised women who give birth to the second or higher order child a significant financial transfer (close in 4 Figure 2: Women’s Occupational Choices, % 5 Figure 3: College Education Figure 4: Married Couples’ Education and Wages 6 Figure 5: Marriage Patterns value to per capita GDP) to benefit the born child2 . Both men and women appear to get married later in life, a trend frequently found in industrialized countries, though Russian statistics can be skewed by age composition of the population that is getting older. The age difference between spouses widened (see Figure 6) by about one year since 1995, though there was a clear peak in this difference in 2005. Perhaps, in the uncertain economic times women were seeking economic security by choosing older, more established partners. Improved standards of living have reduced women’s demand for security: according to Denisova(2012), relative poverty rate in Russia, after staying put at above 20% till since 1995, started to decline steadily in 2004. While examining marriage and divorce statistics by age group, it is clear that younger women stay single longer now, though the trend appears to have reversed between 2005 and 2010. Also, women who are done having children (in Russia, only few women have children past age 35), are increasingly more likely to divorce (See Fig. 7, 8). One of possible interpretations of this statistics is that younger women, by investing in higher education earlier in life, secure stronger positions within the family once married due to their higher value in the labor markets. Though the number of women-housewives have increased after the collapse of the Soviet Union, since 1995 this percentage has not changed significantly (8% in 2011 versus 7.2% in 1995), reflecting continued strong connection of married women to the labor force. This growing strength in the family, however, may also make women divorce later in life, if they assess their ‘outside options’ to being 2 The transfer, also known as “maternal capital”, amounted to about $10,000 in 2007 and is indexed annually according to inflation. The money cannot be spend by women directly and immediately. After three years after birth the maternal capital can be spent on improving child’s living conditions (investment in real estate directly benefiting the child), on child’s education, or can be invested into mother’s deferred retirement account. 7 Figure 6: Average Age of Married Persons married as more attractive, especially as they fulfill their personal goals (or societal obligations) to have children. The hypothesis of stronger women’s position within the family can be also supported by steadily increasing fertility rates since 1995, though one can say that the fertility after the trough of the early 1990’s did not have another direction to go, but up. Figure 9) shows that both the number of children per woman 16-65 year old has generally increased, as well as the number of women with infants. Birth control trends are difficult to interpret. As more women use ‘the pill’ for birth control, abortion remains very common method for controlling fertility (see Fig. 10, 11), though abortion rates do decline. Naturally, college educated women are most likely to use the pill, and least likely – abortion. However, figures also show that both married women and college-educated married are more likely to abort pregnancies than overall women’s population, which questions whether women’s positions in families have strengthened. The examined statistics point out that changing socioeconomic environment and greater value of ‘outside options’ could have improved women’s positions in Russian family. We also observed that a number of indicators have reversed direction of change: labor force participation, marriage and divorce rates, spousal age and pay difference, which could signify a shift powers in ‘the bargaining game’ played within the Russian family. However, we cannot say it with certainty. It is still not clear whether women marry later in life because of continued investment in education or because high quality spouses are sparse; whether women past their fertile age choose to divorce or they are being left by their husbands. In the next sections, after briefly surveying the bargaining literature, I attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the family bargaining dynamics by estimating a simple econometric model. 8 Figure 7: Married Women, % by Age Group Figure 8: Divorced Women, % by Age Group 9 Figure 9: Fertility Indicators Figure 10: Women’s Use of the Pill, % 10 Figure 11: Abortion Rates, % 4 Bargaining and Distribution in the Family Theorists have long acknowledged that the family is not a collection of individuals who act in unison, maximizing family’s utility by pooling and distributing family resources according to some common preference. The common preference or unitary models of family behavior were prevalent till about 1980s, when they were questioned by Manswer and Brown(1980) and McElroy and Horney(1981), who proposed to model family’s dynamics as a bargaining game (see Lundberg and Pollak 1996 for a survey). The bargaining theories in turn have divided in two branches, cooperative and noncooperative, depending on the outcomes of the family bargaining game. Strength of spouses in the bargaining games (children are generally assumed to be excluded from the decision-making process) depends on the number of factors that are external to the family. The examples of such factors are contributions to the family budget made by the husband/wife (wages, non-wage income, transfer payments), resources brought to the family at marriage (such as dowries), external to marriage opportunities (single male-to-female ratio, quality of available mates) or overall family and marriage institutions (divorce and domestic violence laws, religious customs and traditions etc.). Consider the following model which illustrates the essence of the family bargaining mechanism without writing the family’s Nash-bargaining product with explicit values of threat points. A family with two decision-makers, wife and husband, indexed by j = [f, m], maximize their utilities by pooling and then sharing family resources (income and time): max Uj (cj , Lj ), s.t. Cf + wf hf ≤ Φf , C m + wm hm ≤ Φ m , hj + Lj = T, 11 where Cj is personal consumption by a spouse (price normalized to one); Lj is leisure and hj is the time allocated to market work; Φj is a share of joint family resources enjoyed by the wife/husband, with family income Φ = Φf + Φm . Note that each spouse’s share of resources, Φj = s(wj ; X)Φ, depends on their relative bargaining strength s versus (1 − s), which in turn is determined by spouse’s wage wj and other external to the family variables X = [x1 , x2 , ...xn ]. Solution to this problem gives a set of demand functions for consumption goods purchased by the family members, as well as time allocation choices, i.e. labor supply functions: Cj = f (wf , wm , T, X) hj = f (wf , wm , T, X), if no initial endowments are enjoyed by the spouses. Empirical investigations of bargaining positions of spouses in many cases entails an estimation of such demand functions or its derivatives. Evaluating the strength of the bargaining positions of women in particular generally involves assessment of demand for children, resources devoted to children etc. as these ‘consumption goods’ are assumed to be of greater interest to women and greater access of women to the family resources has shown to improve children outcomes such as nutrition, health, schooling etc. s(see for example, Lundberg, Pollack and Wales 1997, Thomas 1990; Haddad & Hoddinott 1994; Maitra 2004 and many others). Empirical evaluations of women’s bargaining power generally consist of identifying a link between external factors affecting their bargaining power (which translates into certain sharing rule of family resources) and observed family’s economic and demographic outcomes: consumption and labor market choices, family size, nutrition, health etc. Different authors use different variables as bargaining power determinants (see survey by Quisumbing and Maluccio 2000). These include spousal assets (as in Doss 1996; Thomas, Contreras and Frankenberg 1999(Thomas, Contreras, & Frankenberg, 1999)), unearned income (Shultz 1990, Thomas 1990), transfer payments and welfare receipts (Lundberg, Pollack and Wales 1997, Rubaclava and Thomas 2000 ). When it comes to the power-allocation link, Attanasio and Lechene (2002) evaluate the effect of wife’s income share on expenditures on various categories of household goods (food, children clothing, services, alcohol). Blundell et al.(2007) analyze how wife’s labor supply decisions (hours, participation rates) respond to changes in husband’s wage, concluding that an increase in the wage tilts resource allocation in husband’s favor. Thomas (1990) investigates the effect of unearned income on nutrient intakes, fertility, child survival and anthropometrics. In this paper I adapt an empirical methodology by Lundberg, Pollack and Wales (1997) who tested the pooling hypothesis of family allocation by using the data from a ‘natural experiment’ in the UK, when a new policy passed in the late 1970s transferred a substantial child allowance to be paid directly to the wife instead of being transferred back to the family in the form of a tax break, generally appearing in the husband’s pay check. It is assumed that environmental changes that take place in Russian society are exogenous; moreover, I pay particular attention to the effect of 2007 law on ‘maternal capital’ that could have strengthened women’s roles in the family similarly to the UK policy change in the 1970s. There are several Russian studies that draw attention to the issues of women’s well-being and family bargaining. A study by Radtchenko and Lacroix (2011) on intra-household allocation before 12 and after the 1998 financial crisis point out that position of Russian women had worsened during this time period. Their empirical approach included an estimation of a system of structural labor supply equations and based on the results they computed an elasticity of the income change for each spouse with respect to the spousal wage. They concluded that an increase in husband’s wage rate increases husband’s share of controlled family resources, but does not substantially benefit the wife (and significantly more so after the 1998 financial crisis), while an increase in the wife’s wage benefits the husband. Selezneva (2010) in her paper titled “What makes Russian women (un)happy?” points towards an existing mismatch between the roles carried out by Russian women and which represents a substantial burden for women: a socially imposed patriarchal family gender role and the actually performed one, where a woman is the provider, as well as the housewife. She looks into data on wages, income sharing, house work and child care and concludes that women’s unhappiness within a marriage rises in 1994-1998 due to the growth of their relative wages and the continuing heavy load of domestic duties. In 2000-2004 she observed a change in women’s preferences, which she suggests could be a sign of emancipation. Kalugina, Sofer and Radtchenko (2009) use a subjective-response question data from the RLMS to study income sharing within the family, utility of family members, inequality as functions of the relative wages and age difference between the spouses. They find that the higher the wife-tohusband wage ratio, the higher is her subjective utility. They also find that during 2000-2003 sharing of resources in the Russian families became more equal. While researcher find the position of Russian women in the 1990’s unanimously poor, the surveyed studies suggest that it might had been improving in 2000’s. Following this lead of above studies I continue the investigation of the question, by using data from 2002 to 2008, in order to find whether further evidence of more equitable sharing and improved women’s positions in Russian families is available. 5 Data and Empirical Model By building on the empirical model by Lundberg, Pollak and Wales (1997), I investigate whether changing economic circumstances and the Maternal Capital Law of 2007 have affected women’s bargaining powers and, as a result, family allocation. I pool RLMS data from 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, the choice determined by two considerations. First, the economic conditions become stable as opposed to the ‘rocky’ 1990s, producing better quality, more consistent data. Second, examination of trends in the Section 2, as well as prior studies, points out that 2002-2004 could have signified a qualitative change in intra-household bargaining dynamics, and I would like to follow up on this perceived change. To further prepare the data set, I match husbands’ and wives’ records from the adult files of the RLMS. I only include families with wive’s age between 16 and 60 years old. I also restrict sample to include families headed by a non-retired person, couples who live separately from the in-laws, with children in the household (0-18 y.o.). Percentages of families that satisfy these criteria are listed in the Table 1. I estimate the following regression equation: Ratiojt = α0 +α1 ChildAgejt +α2 N umChildjt +α3 logRealIncomejt +β(N umChild×Y ear)jt +jt , with dependent variable Ratiojt being a ratio of current real expenditures on children, which 13 includes expenditures on children clothing, education and extra-curricular activities, to family’s expenditures on alcohol and tobacco, which includes expenditures on vodka, wine, beer and tobacco products. It is assumed that expenditures on children is more of interest to and most likely done by the mothers, while spending on alcohol and tobacco products in Russian families is most likely of interest to fathers and is done by fathers. Since I am pooling six years worth of data, and in order to account for the price change, I deflate the expenditures on alcohol and tobacco by the official Russia’s consumer price index on food items, and children expenditures by the price index on non-food items3 . In order to utilize information from zero-alcohol-expenditure families, for such observations I replace zero with 0.01, avoiding the problem of division by zero(resulting in missing observations). Since children expenditures are significantly higher than alcohol and tobacco expenditures, I divide the ratio by 1,000. Among independent variables, ChildAgejt is a vector of dummy variables that indicate whether a family has children younger than 3 years old, children of pre-school age (3 to 7 y.o.), and children of school age (7 to 18 y.o.). N umChildit is a vector of three dummy variables that indicate number of children in the family, with three categories: one-child families, two-child families and families with three or more children. Variable logRealIncomejt allows to control for household income; the nominal family income deflated by Russia’s general consumer price index. Families with reported zero income, as well as income outliers (defined as 1% of the top and the bottom of the income distribution) are excluded from the sample. Descriptive statistics of all variables are presented in Table 1. The set of interaction dummies (N umChild × Y ear)jt is used to track changes in family consumption behavior throughout the selected years. Each variable is found by multiplying a year dummy by each of the three dummies describing family size. The hypothesis is that, controlling for family income and composition, the change in the coefficients on interaction dummies would signify the change in the bargaining regime within the family. Nearly every study of intra-household allocation and bargaining acknowledges presence of endogeneity, since one of the main determinants of bargaining power is spousal wage and income, which first affects family allocation, but then family’s allocation outcomes (such as spousal health, income, education) determines bargaining power. I try to avoid this problem by excluding wages and other endogenous power-determining variables from the set of covariates, and by assuming that changes experienced by families are exogenous to family allocation, while controlling for overall income change. But, certainly further exploration of this issues will be beneficial to the analysis. 6 Preliminary Results The results of the estimations, for the full sample, as well as for subsamples of families with different wife characteristics are reported in Table 2. Since most regression variables are binary, the following variables are excluded: family with children under 3 years of age, single-child families, and interaction dummies for the year 2002 (round 11 of RLMS). Note that both employed and stayat-home spouses were included in the sample. The number of children and family’s income are found to have significant and positive effect on the ratio of children to alcohol/tobacco expenditures. As family size grows, so do the children expenditures, though the marginal increase from an addition of a third child is smaller, possibly due to the scale economies in child-rearing. Families where wives hold college degrees appear to 3 Monthly price indices were obtained from Russia’s Federal Statistical Service, http://cbsd.gks.ru. 14 Table 1: Descriptive Statistics 2002 2004 Households headed by non-retired persons 81.6% 81.9% Percentage of couples living with inlaws 12.9% 11.6% Percentage of couples with children 54.7% 51.4% Expenditures on Children Report children expenditures 85.0% 85.5% Children expenditures 2410.5 2717.4 Real children expenditures 2405.0 2301.9 Average spending per child 1790.3 2041.1 Real spending per child 1786.0 1729.2 % children exp. in household income 47.3% 33.7% Alcohol and tobacco expenditures Report alcohol and tobacco expenditures 73.0% 72.1% Alcohol and tobacco expenditures 113.4 162.5 Real expenditures on alcohol and tob. 112.0 128.8 Alcohol and tobacco exp. In hh income 1.85% 1.65% Household characteristics Age of wife 37.6 37.0 Age of husband 40.4 39.8 Number of children 1.47 1.40 Household size 4.06 4.00 Husband works? 80.6% 80.1% Wife works? 73.4% 72.1% Wife with college diploma 21.3% 21.7% Husband with college diploma 19.1% 18.0% Household income 8528.9 12723.1 Real household income 8398.8 9941.4 Price indices Consumer price index, 1st month 100% 126.2% Price index on food items, 1st month 100% 123.9% Price index on non-food items, 1st month 100% 117.0% Regression variables Ratio of child/alcohol exp, in 1000’s 54.6 59.7 Children under 3 y.o. 17.2% 18.2% Children 3-7 y.o. 21.8% 25.7% Children 7-18 y.o. 77.5% 72.6% One-child family 60.9% 63.1% Two-child family 29.3% 28.0% Three or more-child family 6.2% 4.2% Log real income 8.72 8.92 Females 25 to 35 years old 33.4% 36.6% Females 35 to 45 years old 37.6% 31.1% Number of observations 1269 15 1256 2006 83.3% 11.9% 50.0% 2008 84.4% 11.2% 49.0% Avg. 82.9% 11.9% 51.2% 87.9% 3783.0 2838.7 2810.2 2108.6 26.5% 87.7% 5099.4 3305.7 3843.1 2491.3 23.9% 86.6% 3525.9 2725.1 2637.8 2037.3 32.7% 68.7% 194.0 127.5 1.31% 67.9% 269.8 131.0 1.14% 70.4% 183.2 124.5 1.49% 37.6 40.9 1.41 4.10 82.0% 71.8% 25.3% 17.9% 19539.0 12524.6 37.6 40.4 1.41 4.14 84.0% 74.4% 26.1% 19.1% 31220.4 15709.9 37.4 40.4 1.42 4.08 81.7% 72.9% 23.6% 18.5% 18037.2 11663.6 155.1% 151.6% 132.2% 196.9% 203.3% 153.6% - 100.6 21.1% 24.0% 71.8% 63.1% 28.9% 3.8% 9.18 34.0% 34.7% 132.3 23.8% 30.8% 67.0% 64.0% 27.9% 3.2% 9.45 34.9% 33.0% 87.3 20.1% 25.5% 72.3% 62.8% 28.5% 4.4% 9.07 34.7% 34.2% 1408 1330 5263 spend the most on children in two-children families, and the least - with three children families, while the opposite is true for families where wives have not completed college. When it comes to children age, families spend the most on school-age children, and the least on pre-schoolers. This result holds across all estimated regressions. To determine whether consumption behavior of Russian families had changed throughout the years, let’s examine coefficients on the interaction dummies. It is very clear that throughout 2000’s families moved away from consumption of alcohol towards spending more on children, controlling for changes in household income, price, family composition and age of children. The coefficients increase gradually and consistently, become significant in 2006, and highly significant in 2008, which I think is a clear indication of shifting intra-household dynamics in favor of women due to the Maternal Capital Law of 2007. Since the law benefits women who give birth to the second or higher order child, families with two and three or more children exhibit the greatest change in the expenditure ratio favoring children consumption, according to the model results using the full sample. In absolute terms the largest and the most significant benefit from the law appears to be received by the college-educated women in two-child families, as well as women without college education in three-or-more-child families. When women are split into the age categories, families with one child and with younger wives appear to be spending relatively more on the child, perhaps reflecting the overall change in social attitudes, culture and overall stronger positions of the new generation of women in the Russian family. Overall, coefficients on the interaction dummies are increasing over the years and are highly significant, however, these changes could be due to the overall change in preferences and demand for children items versus alcohol and tobacco. To control for a possible shift in preferences I estimated the same models with added period dummies. The obtained results were generally similar, with coefficients on the added dummies mainly insignificant. 7 Preliminary Conclusions The study conducted here was an attempt to trace changes in intra-household allocation in Russian families with special emphasis on mid-2000s, continuing a series of studies on Russian women that examined women’s well-being throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Unlike previous studies, this paper presents initial evidence that women’s positions could have started to marginally improve in 2000s as Russian economy stabilized. The change in the relative bargaining strength of women seems to have been ‘prepared’ by women in the 1990s, when their economic positions were weak and future uncertain. Younger generation of women now invest aggressively in higher education, move into professional and more flexible service sector jobs, marry later in life, enjoying, as a result, more equal positions in the family. The Maternal Capital Law of 2007 appears to have played a role of a catalyst that could finalize the ‘tipping over’ of the existing status quo in Russian families in favor of women. The changes, while beneficial for Russian women, are not necessarily good news for Russian men and fertility in general. If men continue to expect traditional women and traditional family life, the women might not be able or willing to fulfill such expectations, which already shows up in increasing rates of divorce and acknowledgement by the government of the need to exogenously stimulate fertility. While stronger women are good for society in the long run, short-term, I think Russia is up for a bumpy ride when it comes to the marriage markets and population growth in 16 general. 17 18 Significance levels : child 3 7 child 7 18 two child three child log real income one r 13 one r 15 one r 17 two r 13 two r 15 two r 17 three r 13 three r 15 three r 17 Intercept R2 Variable † : 10% ∗ : 5% ∗∗ : 1% Table 2: Estimation Results (survey weights applied, robust SE) Full Sample Women 25-35 Women 35-45 Wife college -22.87 (15.02) -32.76 (21.75) -27.63 (44.39) -20.52 22.82 (14.00) 2.40 (29.80) 18.75 (39.38) 10.36 ∗ ∗ 38.27 (17.65) 57.71 (28.99) 48.90 (30.85) 95.74† † ∗ 54.94 (29.05) 44.78 (35.44) 130.00 (65.04) -32.27 42.05∗∗ (7.25) 42.82∗∗ (12.48) 52.91∗∗ (15.17) 39.17∗ 1.30 (9.71) 5.40 (13.64) 23.02 (20.95) 36.24† † ∗ 23.36 (12.45) 53.19 (22.80) 11.56 (18.65) 50.75∗ 63.40∗∗ (15.57) 83.79∗∗ (26.96) 76.76∗∗ (28.70) 103.19∗∗ 7.25 (22.84) -8.37 (28.78) 24.04 (44.49) -28.36 77.51∗ (32.98) 31.91 (49.05) 116.48∗ (57.92) 16.25 ∗∗ † ∗∗ 169.32 (46.30) 128.32 (69.22) 259.74 (79.86) 383.87∗∗ 13.28 (44.85) 27.85 (57.32) -66.07 (73.90) 67.08 54.88 (64.84) 2.44 (61.12) -75.13 (99.34) 244.27 218.71† (113.24) 359.31∗ (167.33) -78.76 (92.86) -22.86 ∗∗ -336.85 (62.10) -328.77∗∗ (104.16) -437.26∗∗ (141.87) -318.02† 0.0611 0.0616 0.0914 0.1147 with degree (41.02) (38.39) (56.73) (29.49) (18.16) (21.71) (24.99) (33.38) (58.60) (68.00) (144.26) (48.62) (194.59) (36.12) (166.59) Wife without college degree -24.45† (14.64) 26.71∗ (13.18) 19.99 (15.62) 58.36† (30.93) 35.82∗∗ (7.75) -7.55 (10.90) 17.72 (14.25) 55.04∗∗ (17.46) 19.63 (23.89) 100.10∗∗ (38.12) ∗∗ 91.26 (33.91) 7.45 (48.11) 30.39 (66.25) ∗ 254.34 (124.26) -280.60∗∗ (64.26) 0.0537 References Blundel, R., Chiappori, P., Magnac, T., & C.Meghir (2007). Collective Labor Supply: Heterogeneity and Non-participation. Review of Economic Studies, 74, 417–445. Denisova, I. (2012). Income Distribution and Poverty in Russia. Oecd social, employment and migration working papers 132, OECD, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9csf9zcz7c-en. Goldin, C. (2006). The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Womens Employment, Education and Family. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 96 (2), 1–21. Haddad, L., & Hoddinott, J. (1994). Women’s income and boy-girl anthropometric status in the Côte d’Ivoire. World Development, 22 (4), 543–553. Kalugina, E., Sofer, C., & Radtchenko, N. (2009). Intra-household Inequailty in Transitional Russia. Review of Economics of the Household, 7, 447–471. Laroix, G., & Radtchenko, N. (2011). The Changing Intra-Household Resource Allocation in Russia. Journal of Population Economics, 24, 85–106. Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1996). Bargaining and Dsitribution in Marriage. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10 (4), 139–158. Lundberg, S., Pollak, R., & Wales, T. (1997). Do Husbands and Wives Pool Their Resources. The Journal of Human Resources, 32 (3), 463–480. Maitra, P. (2004). Parental bargaining, health inputs and child mortality in India. Journal of Health Economics, 23 (2), 259–291. Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and Household Decision-Making: A Bargaining Analysis. International Economic Review, 21 (1), 31–44. McElroy, M., & Horney, M. (1981). Nash-Bargained Household Decisions:Toward a Generalization of the Theory of Demand. International Economic Review, 22 (2), 333–349. Quisumbing, A., & Mallucio, J. (2000). Intrahousehold Allocation and Gender Relations: New Empirical Evidence from Four Developing Countries. Fcnd discussion paper 84, International Food Policy Research Institute. RLMS-HSE (1992-2012). Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey-Higher School of Economics. www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/rlms-hse. Rubaclava, L., & Thomas, D. (2000). Family Bargaining and Welfare. Papers 00-10, RAND. Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-Household Resource Allocation: An Inferential Approach. The Journal of Human Resources, 25 (4), 635–664. Thomas, D., Contreras, D., & Frankenberg, E. (1999). Distribution of power within the household and child health. Indonesian Family Life Survey. working paper, IFLS. 19