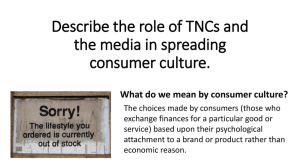

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS

advertisement