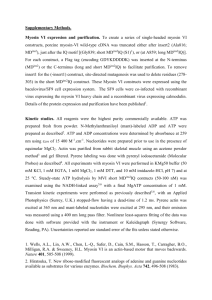

fication of Myosin XI Receptors in Arabidopsis Defines Identi

advertisement