From Where You Live to Where You Spend Time:

advertisement

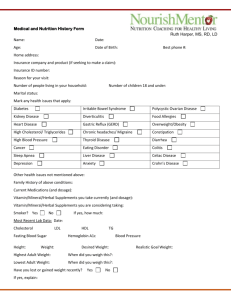

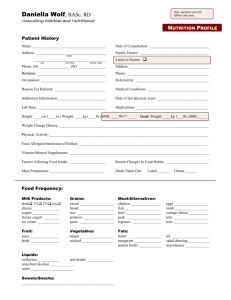

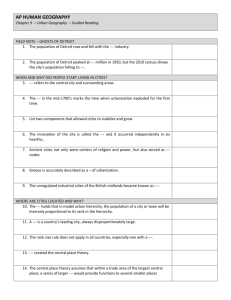

From Where You Live to Where You Spend Time: Environmental Contributions to Obesity Risk Shannon N. Zenk UIC College of Nursing Presentation Overview Environment inequalities Environmental contributions to obesity risk Where you live Where you spend time Activity spaces EMA I will mostly focus on Detroit and Chicago mapusa http://www.s4.brown.edu/mapusa/ Diez Roux and Mair 2010 (Food) environment inequalities Food access differs across neighborhoods: Supermarkets 39.2 39 38.8 38.6 38.4 38.2 38 37.8 37.6 37.4 37.2 Low African American (Tertile 1) Medium African American (Tertile 2) High African American (Tertile 3) Low Medium High Tertiles of Percent in Poverty Food access differs across neighborhoods 2002 2007 Food access differs across neighborhoods Compared to those in the lowest income neighborhoods, schools in highest income neighborhoods had: 32% fewer convenience stores 50% fewer fast food outlets 8 Food access differs across neighborhoods Food access differs across neighborhoods *2006; Sample of the foods assessed Englewood and West Englewood Chicago Lawn and West Lawn % food stores % food stores Whole milk 83% 81% Skim milk 9% 11% Regular cheese 59% 65% Reduced fat cheese 9% 2% White bread 77% 64% 100% whole wheat bread 12% 21% White rice 82% 70% Brown rice 12% 14% Regular ground beef 18% 27% Lean ground beef 2% 7% Fresh vegetables 44% 41% Fresh fruits 33% 37% You’ve got to go out in the suburbs now to get some decent food. And therefore, it’s not available for us in this community. By the time you get to that store and get some fresh fruits and vegetables, you’re going to pass about 30 fast food joints and about 100 liquor stores. - Detroit resident (Kieffer Ethn Dis 2004) Extremely difficult…we don’t have the choices that other communities have. It’s like you choosing from fried chicken, fried fish, fried something. It’s not really a variety of anything in this neighborhood and I wish that it was like when you go up North you have so many varieties…like foods that you can choose from, and we should have that same thing. -Chicago resident Environment and Obesity Risk Where you live Adults in 3 Detroit Communities (n=919)* % Age 25-44 45-64 65+ Female Race/ethnicity African-American White Latino In labor force Married 53 32 15 69 57 21 22 63 25 % Education <H.S. H.S. graduate More than H.S. 36 28 37 Annual HH Income <$10,000 $10,000 - $19,999 $20,000 - $34,999 ≥$35,000 Owns car 27 26 25 22 67 *Detroit Healthy Environments Partnership (Schulz A PI) Data Collection Probability survey of residents in 2002 Reinterviewed in 2008 Environmental mapping and audits Food outlets Street segments Food environment may promote healthier diet African American, Latino, and white women and men in eastside, southwest, and northwest Detroit Food environment may promote healthier diet African American, Latino, and white women and men in eastside, southwest, and northwest Detroit In general, no associations between observed FV availability, selection, price, or quality and intake Large grocery store and convenience store had associations for Latinos than African Americans Also in Latinos, each additional store selling fresh FV was associated with great intake Food environment may contribute to poor diet African American, Latino, and white women and men in eastside, southwest, and northwest Detroit Food environment may affect body weight African American, Latino, and white women and men in eastside, southwest, and northwest Detroit 2002 à BMI change (2002-2008) Large grocery à 3.1 unit reduction in BMI # stores selling fresh FV à 0.49 unit increase in BMI 18 Food environment may affect body weight African American, Latino, and white women and men in eastside, southwest, and northwest Detroit 2002-2008 change in FE à BMI change (2002-2008) Small grocery store/ corner store à 1.1 unit increase in BMI Perceived healthy food access à BMI reduction 19 Environment may affect behavior change African American women in Chicago area (Intervention participants) Women living closer to an indoor shopping mall walked more often No evidence For other environmental attributes That environment moderated intervention effect (during intervention or maintenance phase) 20 Chronic stress * environment à Diet (eating out, snack food) African American, Latino, and white women and men in eastside, southwest, and northwest Detroit Where are we at? Forthcoming in Local food environments: Food access in America (Morland Editor) Next steps: Residential environment Retrospective 10-year, longitudinal study Estimate contributions of residential environment to BMI, metabolic risk (blood pressure, serum glucose, serum cholesterol), and weight management intervention success Powell, Wing, Slater, Fitzgibbon, Gordon, Berbaum, Matthews (PSU) R01CA172726 Tarlov Co-PI Where are we at? Adult studies: All but one focused solely on residential environment Child studies: Most either residential or school environment; few did both Forthcoming in Local food environments: Food access in America (Morland Editor) Environment and Obesity Risk Where you spend time Activity spaces Adults in Detroit (170 total) Pilot 1: Participants in “Walk Your Heart to Health” Pilot 2: Respondents recruited from population-based survey n=39 2007 n=131 2008-2009 92% Female 77% Female Ages 21-71 Ages 25-82 67% African-American 26% Latino 7% White 54% African-American 24% Latino 21% White/Other 36% ≤ High school 64% Beyond high school 55% ≤ High school 45% Beyond high school Data collection (4-7 days) Physical activity Mobility Diet Completed modified 7-day food frequency questionnaire* Three 24-hour dietary recalls (Pilot 2) *Pilot 1: Block Brief 2000 Pilot 2: Block 2005 Spanish Activity spaces 30 Activity space facts Most (>75%) had an activity space larger than residential neighborhood Activity spaces varied tremendously in size with differences by Auto ownership Race/ethnicity Modest associations between activity space and residential neighborhood characteristics (e.g., supermarkets, fast food outlets, parks) Little evidence of demographic differences Activity space environment à diet and physical activity Activity space fast food outlet density + saturated fat intake and – whole grain intake (ES .2-.3) No association residential neighborhood fast food outlet density and diet No relationships for supermarkets or parks Next steps: Activity spaces Activity space segregation and access to health resources and risks Does activity space segregation shape environmental exposures and health? Does activity space segregation buffer effects of residential neighborhood segregation? Does activity space segregation differ by individual demographics? Next steps: Activity spaces Activity space segregation and access to health resources and risks Methodological research on activity spaces - e.g., reliability and validity Recently completed 30 day and seasonal data collection Ecological momentary assessment African American women in Chicago (n=101) Variable Mean or % S.D. Variable Age 44.2 10.5 Per capita income/year Education Mean or % <$7,500 33.7% ≤ H.S. diploma/GED 19.8% $7500-18,750 34.7% Some college 35.6% ≥$18,750 31.7% Bachelor’s degree 22.8% Own or lease auto 64.4% Graduate degree 21.8% Own home 37.6% Employment Technology use Employed full-time 38.6% Use computer daily 62.4% Employed part-time 35.6% Have smartphone 67.3% Unemployed 16.8% Computer at home 81.2% Other 9.0% S.D. Data collection (7 days) Physical activity Mobility Momentary surveys (EMA) (5 x daily) Diet EMA surveys (snacks) Three 24-hour dietary recalls Signal contingent sampling Momentary surveys First daily signal Sleep (Pittsburgh) 5 x daily Diet (snacks) Physical activity Daily hassles (short) Emotions Environmental facilitators and barriers Self-efficacy Other context Last daily signal Daily hassles (long) Descriptive results Snack food intake Ate snack foods at 34.7% of signals Snack food or sweetened beverage at 42.7% of signals Sweet somewhat more often than salty Physical activity Reported engaging in MVPA at 15.7% of signals Mean number of daily minutes of MVPA via accelerometer: 15.4 (18.3) 9.4% of days at least one MVPA bout via accelerometer Descriptive results: Environmental facilitators Good-tasting, high calorie food available 1-2 43% 3+ 47.8% Easily available 59.7% Fast food restaurant, convenience store, or bakery 14.8% Inexpensive 12.2% Environment à Diet (snack food) 1-2 and 3+ good tasting foods associated with 3-6 fold increase in consuming snack foods Perceived easy availability associated with 78% increase in likelihood of snack food intake Fast food restaurant, convenience store, and bakery proximity associated with 2 fold increase in snack food intake Acute stress * environment à Diet (snack food) Predicted probabilities of snack food intake Predicted proabability of eating snack food 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 Easily Available Easily Available not a facilitator 0.2 0.1 0 0 1 2 Daily hassle count: 1 low 2 medium 3high 3 Next steps: EMA Lots to explore with data we have… Integrate GPS, including activity space measures, and EMA survey data Summary Moving from where you live to (incorporate) where you spend time may enhance understanding of environmental contributions to obesity risk Real-time data collection may be useful May need to both increase healthy foods and decrease energy-dense options Acknowledgements Healthy Environments Partnership Many, many colleagues and collaborators including students NIH Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Midwest Roybal Center Healthy Environments Partnership Brightmoor Community Center Warren Conner Development Coalition Detroit Department of Health and Wellness Promotion Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation Friends of Parkside Henry Ford Health System University of Michigan School of Public Health and Survey Research Center