Weight Suppression and Body Mass Index Interact to Predict Long-Term

advertisement

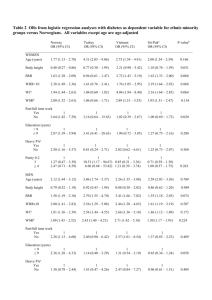

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2014, Vol. 82, No. 6, 1207–1211 © 2014 American Psychological Association 0022-006X/14/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037484 BRIEF REPORT This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Weight Suppression and Body Mass Index Interact to Predict Long-Term Weight Outcomes in Adolescent-Onset Anorexia Nervosa Ashley A. Witt and Staci A. Berkowitz Christopher Gillberg Drexel University University of Gothenburg Michael R. Lowe Maria Råstam Drexel University Lund University Elisabet Wentz University of Gothenburg Research on anorexia nervosa (AN) has emphasized the importance of low absolute body weight, but emerging research suggests the importance of also considering low body weight relative to an individual’s highest premorbid weight (weight suppression; WS). Objective: We investigated whether body mass index and WS at lowest weight (BMI-LW and WS-LW) among adolescents with AN predicted BMI at 6-, 10-, or 18-year follow-up, duration of AN, or total eating disorder duration, including time during which criteria were met for bulimia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified. Method: Forty-seven cases of AN identified through community screening in Sweden were included. Weight and height data were collected from medical records, school nurse charts, and study follow-up assessments. Results: Higher WS-LW was associated with higher BMI at 6-year and 10-year follow-up, and this effect was strongest among those with the lowest BMI-LW values. BMI-LW and WS-LW were positively associated with BMI at 18-year follow-up, but there was no significant interaction. There was no significant association between WS-LW and AN duration or eating disorder duration, although eating disorder duration was longer among those with higher BMI-LW, controlling for WS-LW. Conclusions: Absolute and relative weight status interact to predict weight outcomes in AN over the long term. Results suggest that BMI and WS may be more relevant to the prediction of long-term weight outcomes than to the persistence of other eating disorder symptoms. Keywords: anorexia nervosa, weight suppression, body mass index, outcome individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN; Butryn, Juarascio, & Lowe, 2011; Herzog et al., 2010). Furthermore, WS has been shown to predict longer time to remission from BN (Lowe et al., 2011) and persistence of bulimic symptoms over 10-year follow-up (Keel & Heatherton, 2010). Only two published studies have examined the predictive significance of WS in anorexia nervosa (AN; Berner, Shaw, Witt, & Lowe, 2013; Wildes & Marcus, 2012). Although all individuals with AN are at a low body weight, there is considerable variability in highest past weight (Miyasaka et al., 2003) and thus considerable variability in WS. Although traditionally the field has focused on the significance of objectively low body weight in AN, often measured by body mass index (BMI), emerging evidence indicates that WS may also have predictive utility. Individuals with AN who are higher in WS have been shown to score higher on measures of eating disorder psychopathology, binge eating, purging, and depression, even when controlling for BMI (Berner et al., 2013). Two studies have investigated WS as a predictor of response to treatment in AN and have found that WS, controlling for initial BMI, predicts total weight gain, a faster rate Weight suppression (WS), the difference between an individual’s current weight and highest past weight at adult height, may be an indicator of illness severity and a prognostic indicator among individuals with eating disorders. Weight loss produces metabolic changes that promote weight regain (e.g., MacLean, Bergouignan, Cornier, & Jackman, 2011); in line with these findings, higher WS predicts greater weight gain and frequency of binge eating among This article was published Online First July 21, 2014. Ashley A. Witt and Staci A. Berkowitz, Department of Psychology, Drexel University; Christopher Gillberg, Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Center, University of Gothenburg; Michael R. Lowe, Department of Psychology, Drexel University; Maria Råstam, Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University; Elisabet Wentz, Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Center, University of Gothenburg. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michael R. Lowe, Department of Psychology, Drexel University, Stratton Hall Suite 119, 3141 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104. E-mail: ml42@ drexel.edu 1207 WITT ET AL. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 1208 of weight gain, and likelihood of endorsing binge eating or purging at the end of treatment (Berner et al., 2013; Wildes & Marcus, 2012). In addition, Berner et al. (2013) found that BMI and WS at admission interacted to predict weight gain during residential treatment and psychological symptoms at discharge, suggesting that the biological and psychological significance of WS may depend on the severity of the resulting low BMI. Conversely, the significance of a low BMI may depend on the degree of difference from previous highest weight. While prior research suggests that the prediction of weight gain by WS is likely to involve biological mechanisms, Berner et al.’s results further suggest that psychological response to weight gain in treatment may be influenced by weight history. The present study investigated the long-term predictive effects of WS and BMI, independently and in interaction. We examined long-term weight outcomes as well as duration of illness (for AN and other eating disorders). Data were analyzed from a prospective study of individuals with adolescent-onset AN in Sweden who were examined at intervals for 18 years after onset of AN. We hypothesized that WS would be positively associated with weight at follow-up, as well as with duration of illness. No a priori predictions were made regarding main effects of BMI or interaction effects. Method Sample and Design Data were used from a prospective study of 51 individuals with adolescent-onset AN (48 females, three males). Half of this sample (22 females, two males) consisted of all individuals born in 1970 in Göteborg, Sweden, who met criteria for AN by the age of 18 years and were living in the city in 1985 (except one individual who declined to participate; for details, see Råstam, Gillberg, & Garton, 1989). The other half of the sample included 26 females and one male who had attended the same schools as the other participants and who were born in years adjacent to 1970. Medical, psychological, and neuropsychological characteristics and outcomes in the full sample have been reported in detail elsewhere (e.g., Wentz, Gillberg, Anckarsater, Gillberg, & Råstam, 2009).1 Because of the small number of males in the sample and the potential effects of sex and pubertal development on the variables of interest, the present study included only female participants. Participant diagnosis included physical examination and review of growth charts kept by school nurses, with height and weight data documented at regular intervals from first grade onward. Participants also completed a structured clinical interview to assess Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev.; DSM–III–R) criteria for AN; all participants met DSM–III–R (and, on later review, DSM–IV) criteria for AN. All 48 girls with AN participated in follow-ups 6, 10, and 18 years after AN onset (defined as first symptoms of restrictive eating resulting in weight loss); mean age was 21, 24, and 32 years, respectively, at follow-up points. At each time point, psychological and physical measures were collected in person by research staff. Three participants at 10-year follow-up and five at 18-year follow-up completed assessments by phone. One person declined to participate at 18-year follow-up, but some information was obtained from a family member. The current study used weight and height data from school growth charts and medical records, as well as follow-up data on BMI and duration of illness. The study was approved by the Drexel University and Göteborg University ethical review committees. Weight Variables During First Episode of Illness The highest weight recorded in either school growth charts or medical records, prior to any indications of weight loss associated with AN, was taken as the participant’s highest premorbid weight and was used along with height at that time to calculate highest premorbid BMI (kilograms per meters squared). The lowest weight recorded during the first episode of AN, in either school growth charts or medical records, was used along with height at that time to calculate BMI at lowest weight (BMI-LW). First episode of AN included the period of time between onset of AN and the first time criteria for AN were no longer met, either because the individual met criteria for another eating disorder diagnosis or because criteria were not met for any eating disorder. BMI-LW was typically reached within about one year following AN onset. Weight suppression at lowest weight during the first episode of AN (WS-LW) was calculated for each participant. In adults, WS is typically calculated as the difference between current weight and previous highest weight at adult height. Because some participants had not reached adult height at the time of their premorbid highest weight or the time of enrollment in the study, WS was calculated in BMI units to account for changes in height. We used lowest BMI rather than BMI at diagnosis to capture the greatest degree of WS reached by each participant and to use a standard assessment of low weight across participants. Accordingly, WS-LW was calculated as BMI at highest premorbid weight minus BMI-LW. The data necessary to calculate WS-LW were available for 47 participants. Long-Term Outcome Height and weight were measured at each follow-up point. These values were used to calculate BMI at 6-, 10-, and 18-year follow-up. For the participants who completed follow-up assessments by phone, self-reported height and weight were used. Selfreported weight just prior to pregnancy was used for two individuals who were pregnant at the 10-year follow-up. A study clinician assessed AN duration and eating disorder duration as of 18-year follow-up. AN duration was defined as the number of years an individual met full DSM–III–R criteria for AN between AN onset and 18-year follow-up. Eating disorder duration was defined as the number of years an individual met full DSM–III–R criteria for any eating disorder diagnosis (AN, BN, or eating disorder not otherwise specified). Both the AN duration and the eating disorder duration variables were calculated such that partial years were taken into account (e.g., 1 year 3 months ⫽ 1.25 years). The coding of these variables included review of a compilation of data from multiple assessment modalities. A study 1 The original study included a comparison group consisting of 51 healthy individuals who were matched in age, sex, and school with participants in the AN group. Individuals in the comparison group were not included in the current study because of the nature of the current research question. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. WEIGHT SUPPRESSION IN ADOLESCENT ANOREXIA NERVOSA clinician (M.R.) administered both the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R psychiatric disorders (SCID; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990) and the Morgan–Russell outcome scale (a structured interview that assesses symptoms associated with AN; Morgan & Hayward, 1988) to participants at follow-up time points. Participants were interviewed about symptoms experienced between follow-up points, relapses, and hospital admissions. Information was also gathered from family members, doctors, and nurses, and hospital registries in Sweden were examined until all individuals in the screened population had reached the age of 19. The coding of these variables involved an extensive, multimodal assessment process, and the information gathered is thought to provide a valid assessment of AN and eating disorder duration. Data on AN duration and eating disorder duration have been reported for this sample previously (Wentz et al., 2009). Data Analytic Strategy We conducted a series of linear regressions to examine the associations of each outcome variable with WS-LW, BMI-LW, and their interaction, controlling for age at lowest weight. For each regression, the normality of the residuals was examined using Shapiro–Wilk statistics, with values greater than or equal to .95 considered to indicate adequate normality given the sample size (Royston, 1992). Natural log transformations were applied to BMI at 10- and 18-year follow-up as well as AN duration to obtain normal distributions of residuals. For each regression, age at lowest weight, WS-LW, BMI-LW, and the interaction term were entered simultaneously. Thus, results for each predictor variable, including the interaction term, are from analyses that controlled for all other predictors. When the interaction was nonsignificant, regressions were rerun without the interaction term to examine main effects of BMI-LW and WS-LW, controlling for age. Results Preliminary Analyses Descriptive statistics for the sample are shown in Table 1. Participants were typically in ninth or 10th grade at the initial assessment by research staff, with a mean age of 16.2 years (SD ⫽ Table 1 Sample Characteristics Variable Minimum Maximum M SD Age of AN onset Age at study screening BMI at highest premorbid weight Age at highest premorbid weight BMI at lowest weight Age at lowest weight WS (in BMI units) BMI at 6-year follow-up BMI at 10-year follow-up BMI at 18-year follow-up AN duration (years) ED duration (years) 10.0 11.1 15.5 9.8 9.5 10.5 2.5 13.2 15.4 13.6 0.9 0.9 17.2 19.1 30.9 16.6 18.7 18.7 14.5 31.2 38.0 37.7 14.7 18.9 14.3 16.2 21.1 13.9 15.0 15.3 6.0 21.2 22.0 22.1 3.6 7.6 1.6 1.4 3.3 1.5 2.3 1.7 2.6 3.1 3.9 4.4 2.6 4.4 Note. AN ⫽ anorexia nervosa; BMI ⫽ body mass index; ED ⫽ eating disorder; WS ⫽ weight suppression. Ages are given in years. 1209 1.4). Pubertal status (coded using the Tanner stages of development scale ranging from 1 to 5, with higher numbers indicating more advanced developmental stage; Marshall & Tanner, 1969) was classified as follows: 8.3% as Stage 2, 10.4% as Stage 3, 25.0% as Stage 4, and 56.3% as Stage 5. During the initial assessment, 25.0% of the sample reported binge eating or purging behaviors (an additional 47.9% developed binge eating or purging over the course of follow-up). Results from regression models are shown in Table 2. Assessment of the assumptions of regression indicated that the assumptions of nonmulticollinearity, homoscedasticity, and normality of error variance were met for each model. Long-Term Weight Outcomes There was a significant main effect of WS-LW and a significant interaction between WS-LW and BMI-LW in the prediction of BMI at 6-year follow-up, such that higher WS-LW was associated with higher BMI at 6-year follow-up, and this effect was strongest among those with the lowest BMI-LW (see Figure 1). Among those with high BMI-LW relative to the rest of the sample, the relation between WS-LW and BMI at 6-year follow-up was positive but weak. Those with low BMI-LW and low WS-LW relative to the rest of the sample had the lowest BMIs at 6-year follow-up. For BMI at 10-year follow-up, there were significant main effects of BMI-LW and WS-LW, as well as a significant interaction (with a similar pattern to the one found for BMI at 6-year follow-up). For BMI at 18-year follow-up, there was a significant main effect of BMI-LW and a trend toward a significant effect of WS-LW, but there was no significant interaction. Eating Disorder Duration Neither BMI-LW, WS-LW, nor the interaction term significantly predicted AN duration. BMI-LW significantly predicted total eating disorder duration, such that participants with higher BMI-LW had a longer duration of illness, controlling for WS and age at lowest weight. Eating Disorder Treatment We conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether variability in treatment received might account for the findings described above (i.e., if those higher in WS were more likely to receive treatment, perhaps because of caregiver alarm at the discrepancy from highest past weight, and thereby more likely to experience weight gain). As of 10-year follow-up, 21% of participants included in the present analyses had never received treatment for their eating disorder; 17% had never received treatment as of 18-year follow-up. However, an independent samples t test indicated that participants who received treatment (N ⫽ 39) did not differ from participants who did not receive treatment (N ⫽ 8) on WS-LW, t(45) ⫽ 0.01, p ⫽ .99, d ⫽ 0.01. Participants who received no treatment, fewer than eight sessions of treatment, or eight or more sessions were also compared using a univariate analysis of variance, and no group differences were found on WS, F(2, 44) ⫽ 0.52, p ⫽ .60, p2 ⫽ .023. Receipt of treatment was subsequently included as a dichotomous predictor variable in regression models; results were unchanged. WITT ET AL. 1210 Table 2 Independent and Interactive Predictive Effects of Weight Suppression (WS) and Body Mass Index (BMI) at Lowest Weight WS ⫻ BMI WS Variable B SE p B SE p B SE p R2 BMI 6-yr follow-up BMI 10-yr follow-up BMI 18-yr follow-up AN duration (years) ED duration (years) 0.29 0.63 0.76 ⫺0.34 0.69 0.20 0.27 0.31 0.19 0.32 .159 .025 .018 .099 .038 0.91 0.75 0.46 ⫺0.18 ⫺0.20 0.20 0.27 0.25 0.15 0.26 ⬍.001 .004 .064 .242 .450 ⫺0.26 ⫺0.36 ⫺0.21 0.16 ⫺0.09 0.11 0.15 0.18 0.10 0.18 .029 .033 .133 .619 .647 .34 .25 .15 .15 .13 Note. AN ⫽ anorexia nervosa; ED ⫽ eating disorder. For ease of interpretation, B and standard errors of B values are reported in original units of the outcome variable rather than in log-transformed units. In cases of nonsignificant interactions, the main effect data shown are from models that were rerun without the interaction term. Age at lowest weight was controlled in all analyses. Discussion This study is the first to investigate the long-term predictive significance of WS in AN, independently of and in interaction with BMI. Although prior studies using this sample have found that lowest BMI in absolute terms did not independently predict overall functioning at follow-up (e.g., Wentz et al. 2009), we sought to examine the significance of both absolute and relative weight status with respect to illness duration and weight outcomes. To account for the possibility that WS might be confounded with age of onset, with those who developed AN at younger ages more likely to have lower WS because they had achieved less premorbid weight gain, we controlled for age in all analyses. WS-LW and BMI-LW interacted to predict BMI at 6- and 10-year follow-up: those with higher WS-LW had higher BMIs at follow-up, and this effect was strongest among those with the lowest BMI-LW relative to the rest of the sample. Those with both low WS-LW and low BMI-LW tended to remain at very low BMIs at 6- and 10-year follow-up (relative to the rest of the sample and in absolute terms). There was no significant interaction between BMI-LW and WS-LW in the prediction of BMI at 18-year follow-up. However, higher BMI-LW predicted higher follow-up BMI, controlling for 30 Ave BMI (15.1) 28 BMI (kg/m2) at 6-year follow-up This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. BMI +1 SD BMI (17.4) 26 -1 SD BMI (12.8) 24 22 20 18 16 14 12 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 Weight suppression (mean-centered) 4 5 Figure 1. Interaction of body mass index (BMI) and weight suppression at lowest weight in the prediction of BMI at 6-year follow-up. Weight suppression was calculated in BMI units. A similar pattern was found for the outcome variable of BMI at 10-year follow-up. Ave ⫽ average. WS-LW, and there was a trend toward a positive association between WS-LW and BMI at 18-year follow-up, controlling for BMI-LW. These results suggest that when BMI at lowest weight is held constant, individuals with AN with a history of higher premorbid weight (and therefore higher WS) are likely to experience the greatest weight regain in the long term. It is unclear whether this is because of a predisposition toward higher weight or whether WS produces biological or behavioral changes that promote greater weight gain. However, the interaction effects at 6- and 10-year follow-up suggest that WS is most important as a predictor of weight gain when an especially low weight has been reached. The present findings for weight outcomes are largely consistent with those of two previous studies (Berner et al., 2013; Wildes & Marcus, 2012) and suggest that the previously observed short-term predictive effects of WS and BMI persist over the long term. Interestingly, the poor weight outcomes among individuals with low BMI-LW and low WS-LW parallel prior findings of poor outcome on psychological symptoms (Berner et al., 2013). Berner et al. (2013) suggested that those with low WS and low BMIs may experience increased distress in response to weight gain because they quickly reach or surpass their highest lifetime weight. It is possible that increased resistance to weight gain due to elevated shape and weight concerns might contribute to the poor long-term weight outcomes among this group. Contrary to hypotheses, WS-LW did not predict AN duration or total eating disorder duration, independently or in interaction with BMI-LW. However, controlling for WS-LW, we found that those with higher BMI-LW met criteria for an eating disorder for a longer time period. The mechanisms of this effect should be investigated in future research. Taken together, our findings suggest that WS may be more relevant in the prediction of long-term weight outcomes than in the prediction of long-term persistence of other eating disorder symptoms. These results were unexpected given previous findings that WS and BMI interact to predict psychological symptom change during treatment (Berner et al., 2013). Given the relatively low power in the current study, these results should be replicated in larger samples. In addition, the duration of illness variables did not include subclinical eating disorder syndromes, which may have reduced the sensitivity of these measures. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. WEIGHT SUPPRESSION IN ADOLESCENT ANOREXIA NERVOSA Strengths of this study include the naturalistic, longitudinal design; lengthy follow-up; comprehensive assessment procedures; and use of measured weights rather than self-reported past weights. In addition, because this sample was identified by a comprehensive community screening procedure, selection bias is unlikely to have affected the results. Limitations include the small sample size, which resulted in limited statistical power for analyses of interaction effects, and the possibility that true highest and/or lowest weights occurred in between recorded observations of body weight in some instances. Although we calculated WS-LW and BMI-LW on the basis of lowest weight during the first episode of AN to examine the longitudinal significance of these early weight changes, it is possible that some participants may have experienced even lower weights during episodes of relapse, which may have prognostic significance for the outcome variables studied. In addition, although weight in adolescents is commonly reported using BMI percentiles, our weight-related variables are reported in BMI units (controlling for age in all analyses) because of a floor effect for BMI percentile at lowest weight; this may complicate the comparison of the current findings with other reports of adolescent weight. Finally, because a significant proportion of participants never received treatment, it is possible that these results may not be generalizable to treatment-seeking samples. The present findings have several clinical and research implications. Future studies should investigate whether including WS in the determination of treatment goal weights improves long-term outcome in AN. In addition, the fact that individuals with the combination of lower BMIs and low WS have shown poor outcome in two studies suggests that intensified treatment or different treatment strategies may be required for these individuals. Further research among larger samples is needed to clarify whether WS and BMI predict the maintenance of eating disorder symptoms over time among individuals with AN. The greater propensity toward weight gain found in the present study among individuals with high WS (particularly among those with low BMI-LW) might be associated with maintenance of eating disorder symptoms over the long term because of distress associated with weight gain, as is thought to be the case in BN (Keel & Heatherton, 2010). In addition, future longitudinal studies should examine whether WS and BMI are associated with the emergence and maintenance of binge eating among individuals with AN. Finally, although the mechanisms of the effects of WS in adults are not fully understood, changes in metabolic efficiency and hormonal functioning, in combination with psychological variables, are thought to play a role. Further research should investigate whether similar mechanisms of WS operate in adult-onset versus adolescent-onset eating disorders, as early onset AN arrests normal development and often has lasting effects on growth. 1211 References Berner, L. A., Shaw, J. A., Witt, A. A., & Lowe, M. R. (2013). The relation of weight suppression and body mass index to symptomatology and treatment response in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 694 –708. doi:10.1037/a0033930 Butryn, M. L., Juarascio, A., & Lowe, M. R. (2011). The relation of weight suppression and BMI to bulimic symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44, 612– 617. doi:10.1002/eat.20881 Herzog, D. B., Thomas, J., Kass, A. E., Eddy, K. T., Franko, D. L., & Lowe, M. R. (2010). Weight suppression predicts weight change over 5 years in bulimia nervosa. Psychiatry Research, 177, 330 –334. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.002 Keel, P. K., & Heatherton, T. F. (2010). Weight suppression predicts maintenance and onset of bulimic syndromes at 10-year follow-up. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 268 –275. doi:10.1037/a0019190 Lowe, M. R., Berner, L. A., Swanson, S. A., Clark, V. L., Eddy, K. T., Franko, D. L., . . . Herzog, D. B. (2011). Weight suppression predicts time to remission from bulimia nervosa. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 772–776. doi:10.1037/a0025714 MacLean, P. S., Bergouignan, A., Cornier, M.-A., & Jackman, M. R. (2011). Biology’s response to dieting: The impetus for weight regain. American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 301, R581–R600. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00755.2010 Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1969). Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 44, 291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291 Miyasaka, N., Yoshiuchi, K., Yamanaka, G., Sasaki, T., Kumano, H., & Kuboki, T. (2003). Relations among premorbid weight, referral weight, and psychological test scores for patients with anorexia nervosa. Psychological Reports, 92, 67–74. doi:10.2466/pr0.2003.92.1.67 Morgan, H. G., & Hayward, A. (1988). Clinical assessment of anorexia nervosa: The Morgan–Russell outcome assessment schedule. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 367–371. doi:10.1192/bjp.152.3.367 Råstam, M., Gillberg, C., & Garton, M. (1989). Anorexia nervosa in a Swedish urban region: A population-based study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 642– 646. doi:10.1192/bjp.155.5.642 Royston, P. (1992). Approximating the Shapiro-Wilk W-test for nonnormality. Statistics and Computing, 2, 117–119. doi:10.1007/ BF01891203 Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Gibbon, M., & First, M. B. (1990). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R (Patient ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Wentz, E., Gillberg, I., Anckarsater, H., Gillberg, C., & Råstam, M. (2009). Adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: 18-year outcome. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194, 168 –174. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048686 Wildes, J. E., & Marcus, M. D. (2012). Weight suppression as a predictor of weight gain and response to intensive behavioral treatment in patients with anorexia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 266 –274. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.006 Received September 16, 2013 Revision received April 8, 2014 Accepted June 16, 2014 䡲