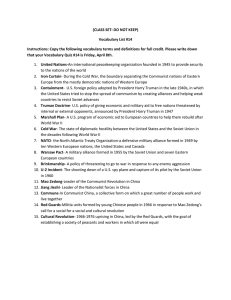

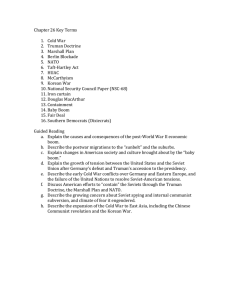

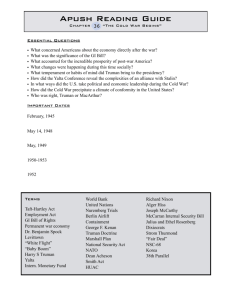

26 The Cold War Abroad and at Home, 1945–1952 D

advertisement