National Focus Group on Problems of Scheduled Caste and

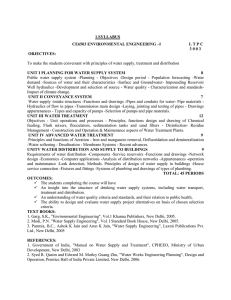

advertisement