More “Bang for the Buck”? Measuring the Efficiency of State Medicaid Spending

advertisement

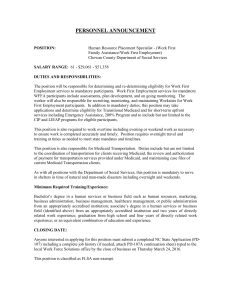

More “Bang for the Buck”? Measuring the Efficiency of State Medicaid Spending June 29, 2010 Presentation to the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting Debra Lipson ● Margaret Colby ● Tim Lake Su Liu ● Sarah Turchin Background Growth in Medicaid costs consistently y outpaced state tax revenues over the past decade, accelerating by 8 percent in 2009 Medicaid payments now account for an average g of 22 percent p of states’ expenditures p Magnitude of Medicaid spending and its share of state budgets leads federal and state policymakers to ask: Are Medicaid dollars spent efficiently? 2 Some State Medicaid Programs Appear to Get More from Their Spending than Others PMPM = per member per month; CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. CAHPS measure: In 2004, among Medicaid recipients age 18 and over who reported making an appointment pp for routine care within the p past six months, the p percentage g who reported p always y g getting g an appointment as soon as they wanted. Source: 2006 AHRQ National Healthcare Quality Report. 3 Research Questions Study purpose: define and measure the efficiency ffi i off state t t Medicaid M di id spending di Research questions: q – What is the relationship between Medicaid cost and quality? – Do D some states t t gett more bang b f th for their i Medicaid M di id buck? – Are certain Medicaid p policies or program p g features associated with higher value in spending?* * Examined in case studies; results not covered in this presentation presentation. 4 Study Framework Efficiency, also referred to as value, in the Medicaid program context: – Viewed from the purchaser perspective – Examined as total Medicaid costs per output or outcome – Compared across state Medicaid programs Relative to other states, efficient Medicaid spending produces: – Better outcomes for same cost – Similar outcomes for lower costs 5 Approach and Methods Developed exploratory efficiency measures: – For four major groups of Medicaid beneficiaries • Children • Adults • People with disabilities • Elderly – U Used d currentt M Medicaid-specific di id ifi quality lit measures and d available data, despite limitations – Used relevant Medicaid costs: all service and administrative costs but not DSH or UPL add-ons To compare states, used the median scores as benchmarks to reduce the influence of outliers 6 Exploratory Efficiency Measures 28 sets of cost and quality measures, divided i t five into fi domains d i 1. Adults—HEDIS and CAHPS measures 2. Children—HEDIS measures 3. Children—National Immunization Survey and National Survey of Children’s Children s Health 4. Disabled—National Core Indicators (annual survey of people with developmental disabilities) 5. Elderly—Nursing Home Compare (MDS measures for the elderly residing in nursing homes for three or more months)) HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set MDS = Minimum Data Set quality indicators for nursing home residents 7 Findings: Two- to Four-Fold Variation in State Costs Among g all Medicaid enrollees,, PMPM costs varied by a factor of three ($272 to $860) Among populations covered by quality measures in 2006, the state variation in costs differed by yp population p group: g p – Greatest variation for those with developmental disabilities: $ $2,495 , to $9,113 $ , PMPM – Least variation for children from birth to age 17: $141 to $556 PMPM 8 Findings: Most quality measures had tightly clustered scores, but some varied greatly 100 0 100.0 o t e ta r e d o M e va H 80.0 t o N o d o h w ts n ) 60.0 e6 id s 0 e0 R2 ( e in ma oP He g re in sr ve u S 40.0 N ya tS ‐g n o L yl r e 20.0 ld E f o e ga t n e cr e P 0.0 $0 Pregnant Females Who Received at least 80% of Recommended Prenatal Care Visits (HEDIS 2007) and PMPM Costs (2006) (N=22) Elderly Long‐Stay Nursing Home Residents Who Do Not Have ‐ Moderate to Severe Pain (NHC 2006) and PMPM Costs (2006) (N = 49) DCHI MD MA NJ CT NY RI SC NH ALMI VTPA WI MN NC ND IN TXMO AR VAMI WV DE LASD FL TN IA KY ID CA IL KSGA NE CO NM MT OR OH WA WY OK NV la 100.0 ta n re P d e d n e m 80.0 m o c e R f o % 0 8 n a h t 60.0 r e ta ) e r 6 0 G0 d (2 e vi tsi s e c iV e R 40.0 o h w s e la m e F t n a 20.0 n g e r P f o e ga t n e rc 0.0 e P $0 AK UT No Statistically Significant C ‐Quality Relationship Cost Q t lit R l ti hi $2,000 $4,000 $6,000 $8,000 $10,000 PMPM Costs KY WV OH HI IN CA MD MA NE NM VA NJ CO WI DC MN FL No Statistically Significant C ‐Quality Relationship Cost Q t lit R l ti hi $200 $400 $600 $800 PMPM Costs 9 RI NY PA TX MI $1,000 $1,200 $1,400 Findings: Few significant correlations between cost and quality Among 28 measures, we found only three statistically i i ll significant i ifi cost-quality relationships – E.g., well well-child child visits for children age three to six enrolled in capitated arrangements Butt th B the three th did nott tell t ll a consistent story about the relationship between cost and quality – – Two positive correlations (higher costs associated with higher quality) One negative correlation (lower costs associated with higher quality) Children Ages 3‐6 With At Least One Well‐Child Visit in ‐ the Past Year (HEDIS 2007) and PMPM costs (2006), N= 25 100.0 ) 6 0 0 (2 ra e Y ts a 80.0 P in ti si V ld i h C ‐ll e W 60.0 e n O ts a e L ta h ti w , 40.0 6 ‐ 3 s e g A , n re d il h C 20.0 f o e ga t n e rc e P MA DC NY MDRI CA TXWV WV NJ OHMI FL HI VA IN NE WI PA KY MN NM WA MO CO OR Statistically Significant Cost‐Quality Relationship p < 0.05, R² = 0.204 00 0.0 $0 $100 $200 $300 PMPM Costs 10 $400 $500 Scoring State Performance on the 28 Exploratory Efficiency Measures Benchmarks are based on the median score for each cost or quality measure among states with data State Quality Score Higher-quality, lowercost states Higher-quality, higher-cost states Score=1 Score=2 State Quality Score BenchBench mark (Median) Lower quality, lower Lower-quality lowercost states Lower quality, Lower-quality higher-cost states Score=2 Score=3 State Cost Benchmark (Median) 11 State Cost State Domain Scores and Tiers—HEDIS Measures for Children (2006) Tier A Tier B Tier C California Kentucky Michigan Nebraska New York Colorado Florida Hawaii Maryland Massachusetts New Jersey Ohio Rhode Island Virginia West Virginia Wisconsin D.C. Indiana Minnesota Missouri New Mexico Oregon Pennsylvania Texas Washington 15 month olds:6 or more visits 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 3 3 HEDIS: Well-Child Visits 15 month olds: 4 or Children Ages 3-6: more visits at least one visit 1 2 1 2 2 2 1 3 1 2 2 2 2 2 3 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 2 2 3 3 2 2 3 3 3 2 3 2 2 2 12 Children ages 12-21: at least one visit 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 2 1 2 State Domain Tiers—HEDIS Measures for Children (2006) 13 Findings: Patterns Within Measure Domains Within each domain, state scores on exploratory efficiency measures were generally correlated with one another It was rare for a state to have the highest or lowest scores for all measures within a domain Many states lacked data for multiple domains – Only y eight g states had q quality y data and therefore had measures in all five domains for 2006 14 Findings: Patterns Across Measure Domains Varying performance across the five domains was common – Few states were high or low performers in all measures or domains; all had different strengths and weaknesses States that frequently q yp placed in Tier A or C did not uniformly share characteristics such as program size, reliance on managed care, or underlying medical costs 15 Conclusions Because cost and q quality y vary y widely y across states and for most measures, but do not appear to be correlated, there may be opportunities t iti to— t – Lower or control costs without sacrificing quality – Increase quality without increasing costs, particularly in states whose absolute scores on quality measures are lower than the median 16 Policy Implications Results offer national benchmarks for assessing the value of state Medicaid spending relative to quality Policymakers seeking to improve the value of Medicaid spending must consider both sides of the value equation: – Lowering costs in ways that do not harm quality – Improving I i quality li for f li little l or no extra cost 17 Limitations and Avenues for Future Research Large number of states excluded from many measures due to lack of data – Some measures have data from only 18 states Comparable Medicaid quality measures or data unavailable for many Medicaid enrollee groups Costs in exploratory efficiency measures are not risk-adjusted 18 For More Information Please contact – Debra Lipson • dlipson@mathematica-mpr.com – Margaret Colby • mcolby@mathematica-mpr.com Thanks to our sponsor – U U.S. S D Department t t off H Health lth and dH Human S Services, i Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Health Policy 19