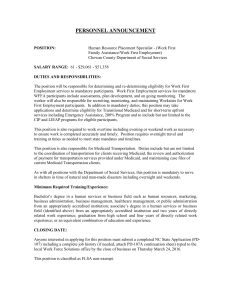

Who Pays? Research Question Nursing Home Share of Total Health Care Expenditures

advertisement

Nursing Home Share of Total Health Care Expenditures Moral Hazard in Nursing Home Use 9 8 7 6 % David C. Grabowski Harvard Medical School 5 4 3 Jonathan Gruber Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2 1 0 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 Who Pays? Private Other insurance 6% 8% Medicaid 47% Out of pocket 27% Research Question • Do more generous state Medicaid rules encourage greater nursing home use, • Or, is nursing home care an option of “last resort” that does not respond to public policy? Medicare 12% Background • Medicaid eligibility for nursing home care determined by income and asset tests • Some states allow medical and nursing home expenditures to count against income test – Medically needy rules – 209(b) status • Spousal impoverishment rules – 1990 Medicare Catastrophic Care Act Theory • Std market clearing model. Individuals desire nursing home care and also want to leave bequests for their heirs • Loosening Medicaid eligibility standards is thought to have two effects: – Mechanical. More individuals eligible for services – Behavioral. Allowing individuals to qualify for Medicaid while retaining more assets will raise total demand for NH care 1 Previous Research • Cutler & Sheiner, 1994; Hoerger, Picone & Sloan 1996; Norton, 1995; Norton & Kumar, 2000; Reschovsky, 1996 • At most, previous studies find modest effect of Medicaid rules on utilization • Concerns – Unobserved heterogeneity – Selectively control for eligibility standards – Somewhat outdated Data • National Long-Term Care Survey – 1982, 1984, 1989, 1994, 1999 – Surveys community and institutional populations – Data are longitudinal with replacement • Survey of Medicaid program rules • Medicaid payment rate and nursing home beds from Harrington et al state data books Variables General Empirical Approach NHist = ßPOLICYst + γXist +νi + ηs + λt + (λt × νi) + εist Where: NHist is nursing home use for person i in state s of year t, POLICYst is a vector of state motor vehicle laws Xist is a set of individual level control variables νi = marriage fixed effects • Policies – – – – – – • Covariates Spend-down provision Income test Asset test Spousal asset test Medicaid payment rate Beds per 1,000 elderly – – – – – – Age Race/ethnicity Gender Number of children Income (endogenous?) Health (endogenous?) ηs = state fixed effects λt = year fixed effects εist is a randomly distributed error term Methods • Estimate probit models – Present marginal probability effects • Use NLTCS weights • May be autocorrelation in outcomes and policies – Cluster standard errors within states – Present results that include state-specific linear time trends Descriptive Statistics Variable Nursing home use Spend-down provision Income test (1999$) Asset test (1999$) Spousal asset test (1999$) Medicaid per diem (1999$) Beds per 1,000 elderly N Mean (SD) 0.046 (0.210) 0.66 (0.47) 619 (1,026) 3,234 (1,323) 12,928 (26,372) 84.13 (25.79) 53.30 (15.49) 25,697 2 Results Robustness Checks Basic Model w/ Time Trends Spend-down 0.002 (0.004) 0.006 (0.007) Income test ($1,000s) 0.001 (0.001) 0.001 (0.001) Asset test ($10,000s) -0.013 (0.010) -0.012 (0.008) 0.000029 (0.005) 0.004 (0.004) Medicaid rate ($100s) -0.007 (0.014) -0.009 (0.020) Beds per elderly 0.330 (0.187) 0.079 (0.438) 24,417 24,417 Spousal assets ($100,000s) N • Synthetic panel approach – NLTCS includes lifetime history of NH use – Age everyone in NLTCS back to 65 • Transitions model – Conditional on individuals in community at previous NLTCS wave • Differences-in-differences-in-differences model with spousal impoverishment rules – Pre vs post MCCA; single vs married; high vs low asset states Conclusions • Results consistent with inelastic demand for nursing home care – No statistically significant effects – Standard errors reject relatively small effects • Changes in Medicaid eligibility standards may potentially increase Medicaid share, but little evidence of significant behavioral effects – From a policy perspective, contraction of Medicaid eligibility will not decrease total utilization of services 3