Topic 5: Macroeconomic policy. Part 1: Fiscal policy 1 Fiscal policy

advertisement

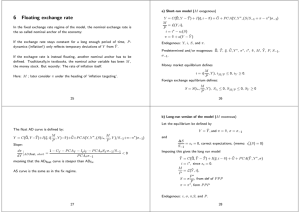

1 Topic 5: Macroeconomic policy. Part 1: Fiscal policy Øystein Børsum Temporary Lecturer, University of Oslo Fiscal policy • Macroeconomic stabilisation and fiscal policy in the AS-AD model (reading: B&W 15.3) • Scope for demand management: Slope of AS, adjustment lags, policy and effectiveness lags (reading B&W 16) • The budget surplus • Managing the public debt (reading: B&W 15.4 and 15.5) • Supply-side policies (reading: B&W 17) April 18, 2005 2 1 1.1 Macroeconomic stabilisation and fiscal policy in the ASAD curve under a fixed exchange rate: AD model Y = C(Ω̄, Y −T̄ )+I(q̄, i∗ −se(S)−π̄)+Ḡ+P CA(Y, Y ∗, (S/S−1 +π−π ∗)σ−1) In the AS-AD model, expansionary fiscal policy dG > 0 has the following effects: AD curve under a clean float regime: Y = C(Ω̄, Y −T̄ )+I(q̄, i( M M , Y )−π̄)+Ḡ+P CA(Y, Y ∗, (S(i∗, , Y )/S−1+π−π ∗)σ−1) P P shift in AD from dG: dπ ¯¯ −1 >0 ¯AD,short = dḠ P CAσ σ−1 Y % implies i % and therefore σ % and I &. Government expenditure crowds out private investments and net exports. Total effect on Y depends on sensitivities in this ”interest rate channel”: Ir iY for investments, and SY = SiiY . If capital mobility is high, the total effect may be small. 3 The initial shift in AD from dG is the same, however this time, monetary policy accommodates G % to keep i constant in order to defend the fixed exchange rate. No crowding-out. Conclusion: Fiscal policy has greater effect under a fixed exchange rate. Dynamics: Increased inflation will shift the short-run AS curve upwards. Long run: 1) Long-run AS curve is vertical 2) The budget must balance, so G must fall. 4 1.2 Scope for demand management: Slope of AS schedule and adjustment lags Under imperfect capital mobility: Baseline model assumes perfect capital mobility. Modifications with imperfect capital mobility: 1. Only minor in float case: Regular money market analysis. Still positive relationship between i and S in the FX market 2. In the fixed exchange rate regime (full) sterilisation is now possible: Independent control over M (and i). G % implies i % reducing the expansionary effect. The rationale and scope for “activist fiscal policy” is a main controversy in economics. Reading: B&W (chp 16): Scope for demand management is larger if: Short-run AS curve is flat and the long run is indeed long. Long run = Time before the short-sun curve shifts to the vertical long-run position. (Keynes: ”In the long run, we’re all dead”) Answer hinges on: • Slope of the Philips curve: Level of trade-off between U and π • Time of adjustment for core inflation 5 • Time of adjustment for unemployment towards the natural rate 6 1.3 Scope for demand management: Policy and effectiveness lags Overriding concern: Status of the Phillips curve natural-rate model itself. Is the long run AS curve vertical? Aukrust/bargaining model: π stabilizes at π ∗ at “any” level of unemployment. ”Long and variable lags” (Friedman) makes it difficult in practice to carry out the intention of counter cyclical fiscal policy. 1. Recognition lag (data measurement) 2. Decisions lag (political system) 3. Implementation lag (administrativ process) 4. Effectiveness lag (from change in instrument to effect in target) 7 8 1.4 The budget surplus Long-run: Government expenditure = income (taxes). Balanced budget a preliminary benchmark for a neutral fiscal policy (assuming no growth). Short-run: Taxes work as automatic stabilisers. Characterises the budget as truly expansionary or contractive in levels. Popular among politicians. Note: Computing Ȳ is not free of assumptions. Instead of exogenous taxes T̄ , assume a simple tax-function: Note: Does not say anything about the effect dY /dG. T = τY The government primary surplus T − G will depend on the activity level Prudent governments keep down/revert deficits in order to maintain financial independence and public confidence. Government deficits sometimes become the overriding concern of fiscal policy. τY − G The activity corrected surplus is: τ Ȳ − G Decomposition of the budget surplus in activity dependent taxes and activity corrected surplus: τ (Y − Ȳ ) + τ Ȳ − G 9 1.5 10 Managing the public debt: Debt financing and debt stabilisation Change in real public debt dB, is equal to the total budget deficit dB = G − T + rB (15.1) where r is a real interest rate and rB the real interest payments (“debt service”). Over time, governments must stabilize the debt-to-income ratio B/Y B d( ) = 0 Y (*) Differentiate d(B/Y ): dB dY Y dB − BdY B = − 2B d( ) = Y Y2 Y Y so that (*) can be written (15.3) To stabilize debt at a certain level, the primary surplus T − G must equal (r − g)B. Easier when interest rates are low and growth is high (e.g. Europe in the 1950’s and 1960s). With the Maastricht treaty (1991) and the Stability and Growth Pact (1997): European countries have chosen deficit reduction. Has contributed to high European unemployment, though only temporary according to AS-AD with Phillips curve. Modifications: Seigniorage and inflation tax. Not all public debt is interest bearing: By printing money, the government obtains an interest free loan from the public. This ”income” is called seigniorage. Without the monopoly right to printing money the government would have to issue bonds and pay interest. The Stability pact forbids this form of debt financing. B G−T B d( ) = + (r − g) Y Y Y Moreover, increased money supply drives up inflation, thus reducing the outstanding governments debt in real terms (when government debt is fixed income 11 12 2 assets). This ”gain” is referred to as inflation tax. Note: Expected inflation is already accounted for in the nominal payments. Adoption of inflation as an explicit target of monetary policy has greatly reduced the existence of inflation taxes. Supply-Side Policy (B&W ch 17) Policy measures intended to raise potential (instead of actual) GDP are known as supply-side policies. Some examples from B&W (17): • Increase competition among firms • Reduce externalities from subsidies and taxation • Improve labour market incentives Supply-side policies often involves reforming previously established systems or benefits. Ex: Dismantling state monopolies, abolishing protectionist tariffs, cut back unemployment benefits, etc. 13 Moreover, it may take a long time before these policies have the intended effects. Needless to say, supply-side policies are always contested. Note in particular: • Box 17.5 on active labour market programmes. Comparatively low Nordic unemployment rates seems to be due to active programmes. Contested by Rødseth and Nymoen (2003). • Role of labour unions. Absence of unions often viewed as producing more flexible wages. However, coordinated bargaining (centralised, union based) might entail quite flexible wages as well. 15 14