Race, Region, and Vote Choice in the 2008 Election:

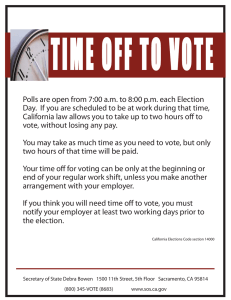

advertisement