2.1ibais In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Submitted to the

advertisement

2.1ibais

on

CALCIUM, 21-10SPHORUS AND VITAMIN D

NE:qUIMMENTS OF GROWING CHICKS,

Submitted to the

OREGON STATE', AGRICULTIMAL COLLEGE;

.101.11111111011.~1.11

ANNIONIONIMINIMMINIOD

11111.11011111.01110

In partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the

Degree of

MASILR

SCIBNCE

by

Walter Knowlton Hall, 3.S.

May 1933.

APPEOVLD:

Signature redacted for privacy.

Profe eor o Agricultural Chemistry*

Signature redacted for privacy.

tild

of Department of Ghemistry

i)

Signature redacted for privacy.

Chairman of Committee on Graduate Study*

Acknowledgement

These studies were conducted as a part of a cooperative project between the Departments of Agricultural

Chemistry, Poultry Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine

and were made possible by a research fellowship created

by the F.C. Booth Co., Inc., San Francisco, California.

The experiments reported were conduoted under the immed-

late supervision of Dr. J.E. Haag, Nutrition Chemist of

the Agricultural Experiment Station. The writer wishes

to acknowledge his appreciation of the assistance and

many helpful suggestions rec ived from him, and from

other members of the above departments.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

?age

INTRODUCTION

HIsTORICAL

1

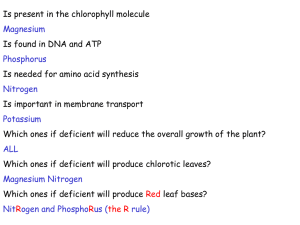

The Physiological Action of Electrolytes on Organisms and Excised Tissue

1

Sodium and Potassium

2

CEllcium and Magnesium

3

Calcium and Phosphorus Reletionships

Calcium and Phosphorus Metabolism in

Poultry

4

6

THE; psomism

12

GENERAL PROCEDIM

13

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS AND DATA

13

DISCUSSION

25

SUMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

29

BIBLIOGRAPHY

31

CALCIUM, PHOSPHORUS AND VITAMIN D

RE4UIRLIC6NTS OF GROWING CHICKS.

INTRODUCTION

The problems involved in the determination of the

calcium, phosphorus and vitamin D requirements of grow.

ing chicks are much more complex than was commonly sup-

Posed to be the case only a few :pears ago. As a result

of studies in the field of pure physiology, and of rick.

eta in experimental and farm animals, we have come to

recognize the existence of important but more or less ob.

scure interrelationships between calcium, phosphorus and

vitamin D requirements. In recent years considerable

importance has been attached to the significance of Ca/P

ratios in the nutrition of experimental and domesticated

animals, and of poultry in particular. Because of the

interest in such ratios, and because of the importance

of a proper understanding of the principles involved the

writer wishes first to review briefly some of the work

leading to the development of the idea that a more or

less balanced condition among the mineral salts in the

diet is essential to normal nutrition.

HISTORICAL

The ?hYsiological Action of :alectrolytes on Organisms

and Lxcised Tissue, The concept of a physiologically billsnood condition among the mineral ions occuring in the

normal environment of living organisms is largely the results of studies first conducted in the field of what may

be called pure physiology.

Nesse in 1869 (see Sollman 1924) determined the isosmotic concentration of pure sodium chloride solutions

for frog tissues. Such isotonic solutions, known as nor-

mal saline solutions are still used for blood dilution

or histological examination of tissues. Ringer (13801882, 1882-1883 , 1882-1883, 133C) found such solutions

unsatisfactory for the maintanace of the normal reac.

tivity of frogb muscles or of the beat of a perfused

frog's heart unless there was a balancing of the physiological action of sodium ions by potassium and calcium ions.

Herbst in 1897 (wee Needham 1931) showed that sea urchin

larvae needed all tbe constituents of sea water for normal

development. Previous to 1900 these inorganic ions were

thought of merely as nutrients. In 1900 Loeb (Loeb 1916)

stated his now well known theory of physiologically balanced salt solutions which he had formulated from the results of his extensive experiments. Loeb's statement

was as follows: "-----the theory of physiologically balanced salt solutions b which we mean that in the ocean

-2-

(and in the blood or lymph) the salts exist in such ratio

that thsy mutually antagonize the action which one or

several of them muld have if they were alone in solution."

As may be seen from this statement of Loeb's, the counterbalancing of the physiological effects of various ions

or croups of ions, are often spoken of as "antagonism."

The conception of physiologically balanced salt

solutions has received additional support as the result

of the in,Y,ction of various salts (Robertson 1920,

nett 1903, Haag 1926, Sjollema 3ickles and Van der Kaay/32

Sollman 1924) into the circulation of higher animals and

has been resorted to (Sollman 1924, iobertson 1920 7ive

reviews) in an attempt to explain the cathartic action of

saline purgatives.

Thera aro also nunerous facts and experiments in the

field of human and animal nutrition which have variously

been thought of as involving the phenomena of ion antagonism, a few of the more important of which will be

cited below.

Sodium and Potassium. 8ungets (1902) work on salt

craving appears to be the first important study of what

might now be looked upon as a case of ion antagonism in

animal nutrition. He thought it remarkable that of all

the salts in the diet, herbivores craved only sodium

chloride. Herbivores take three to four times as much

.3.

potassium in the diet as carnivores which experience no

such craving. This led 6unge to cilieve that the salt

craving was due to the high potassium intake He found

that eating of potassium. salts caused an increased excretion of sodium which led to salt hunger. He cites an

enormous amount of evidence in support of his theory. The

findings of a number of investigators have not entirely

supported 3unRets theory, Miller (1923, 1923a, 1926)

interprets his findings from the feeding of rats and

pigs as not entirely in support of 3unge's theory, The

conclusion of Hart, McCollum, Steenbock and Humphrey

(1911) and of Harrar (1925) are not in accord with !lunge

theory. However Gerrard (see Haag 926) interprets his

experiments with dogs as favoring Bungels theory.

Sherman (1932) expressed what is perhaps the best

summary of present day opinions by saying of 3ungels theory,

"While :3-tinge's explanation may not be entirely adequate in

detail, there seems to :A3 little doubt as to the correct.

ness of his main deduction."

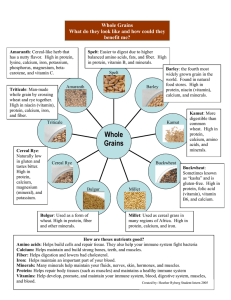

Calcium and Mag,nesium. Magnesium salts whether in.

jected into the body or taken orally, tend to cause a

loss of calcium from the body (Haag and Palmer 1923,

Mendel and iz,enedict 1909, Forbes et al, 1922, 1924, Bogert

The harmful effects of excessive

amounts of magnesium in the diet are said to be alleviated

and McKittrick 1923),

-4-

in part at least, by the presence of liberal amounts of

calcium and phosphorus (Hart and Steenbock 1911, 1913,

Haag and Palmer 1928), Other investigaters place lass

emphasis on the harmful effects of magnesium in ordinary

diets (Hart,. Steenbock and Morrison 1917, Elmsbie and

Steenbook 1929, Medea .926, Huffman at al. 1930). Moriquand (1931) found that the ingestion of mapelesium carbon-

ate intensified rickets. euckener, Martin and lnsko (1932),

Mussehl at al. (1930), the Idaho-.experiment Station (1929),

Wheeler (1919) found either an intensification of rickets

or a serious disturbance of calcium and phospiorus metabolism when hi h levels of maencsinm were fed to chickens.

eelcium and eeospeorus ielationshiat The importance

of Ca patios has become increasingly apparent since the

interrelation of the inorganic nutritionally essential

elements was first emphasized by some of the earlier workers (McCollum and Davis 1915, Osborne and Mendel 1918).

McCollum et al. (1921) found that diets containing an

amount of phosphorus which Sherman and Papenheimer (1921)

had shown would prevent rickets, became rickets-producing.

when enough calcium was added to raise the Ca/P ratio to

approximately 4.0. As a result of this work it has been a

common practice to use high calcium-low phosphorus diets

in the production of experimental rickets. Meigs, Turner

and associetes (1926) have expressed the opinion that a

Ca/P of 2.0 is unnecessarily high for cows. Hart and

Steenboek (1930) were of the opinion that for milking

cows, a ratio of 1.3 was optimum. Lindsey, Archibald

and Nelson (1931) found that for all ages of cattle, a

Ca/P ratio of 2.0 was satisfactory. According to Reimer

and Smuts (1932) a Ca/P ratio of between 1.4 and 1.2 ap.

peared not far fram optimum for pigs, aethke and co-workera (1930) report that within certain Anita Ca/P ratios

are more important than the concentration of these elements

in the rations, and that wide Ca/P ratios increase the vitamin D roquirements. In a later paper Bethke et al. (1932)

again emphasize the impo..tance of Ca/P ratios. As a result of a quite comprehensive stud, a Ca/P ratio between

1 and 2 was found to iv the optimum ratio for rats. A

short nota in trk Annual Report of the Wisconsin Agricultural axperiment Station (1928-29) suggests 1.5 as the

.accepted Ca/P ratio for neaunals. Kramer and Howland (1932)

claim that in Mao absence of vitamin rig the Ca/P ratio of

the diet Jo reflected in the blood of an animal, isrown,

Shohl and collaborators (1932) state that "...Both the

level and ratio of calcium to phosphorus are necessary to

-characterize adequately the ricketogenic properties of a

diet.

It therefore appears that in the prevention or production of rickets,' at least fourfkotors must be considered, These are the levels of calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D

.6.

(or its equivalent) and the Ca/P ratio. In addition, the

acid-base balance of the diet and the magnesium level may

at times rsquire some cansideration.

Calcium and Phosphorus Metabolism in Poultry. In-

tensive studies of the calcium and phosphorus roquirs.

ments of poultry have been made since the discovery (Hart,

Halpin and Steenbock 1922) that nutritional leg weakness is

to be regarded as analagous to rickets in other animals.

Mails these studies have made possible the practical elvrina_

tion of such disorders, they have also helped to emphasize that Calcium and phosphorus nutrition is conditioned

by a number of complicating factors.

Hart, Halpin and Steenbock (1922) demonstrated that

leg weakness in chickens could be prevented b7 feeding

cod liver oil. This has been abundantly corroborated by

subsequent investigations (Dunn 1924, Plimmer, Rosedale

and Ra7mond 1925) and practical experience.

A number of fish oils other than cod liver oil have

been shown to he effective carriers of vitamin D. Since

cod liver oil has been used no widely, it is often used

as a standard of comparison for other fish oils. Bills

(1927) found sardine (pilchard) similar to cod liver oil

in vitamin D content. Nelson and Manning (1930), Gutter.

idge (1932, 1932a), Halvorson and Lachat (1932, 1932a)

Truesdell and Culbertson (1933) have confirmed Bill's

results. Asmundson et al. (1929) found sardine oil inferior to cod liver oil for bone calcification of chickens.

Since the various studies cited above have shown that crude

unassayed sardine oil is subject to the same variation

in vitamin D content as is crude cod liver oil, this dis.

creptancy probably may be explained in that way. Sur

bot oil and tuna fish oil have also been shown to be

similar to cod liver oil with respect to their vitamin D

content (Halvorson and Lachat 1932, Truesdail and Culbert.

son 1933). Dog fish liver oil seems to be inferior to cod

liver oil,

(Halvorson and Lachat 1932).

Good salmon oil

Is also equal to good cod liver oil (ielliot and eelson et

al. 1932, Tolle and Nelson 1931).

Irradiated ergosterol ('Viosterol") is not well util.

ized as a source of vitamin D by poultry as it takes from

forty to one hundred and twenty times as many rat units

in this form as in the form of fish oils to prevent rickets

and produce normal erowth,(Journal of the American Medical

Association, :Editorial, 1932, Masqe;ngill and Nussmeier 190,

Hall et al. 1931, Steenbock ot al. 1932, Mussehl and Acker.

son 1930, Russel and Klein 1931, King and hall 1931). The

Inability of chicks to efficiently utilize irradiated

ergosterol has not yet been satisfactorily explained,

Vitamin D may be produced in the chicken by exposre to ultraviolet irradiations or sunlight. 6unlight seems

to be moreeffective than artificial ultra violet irradia.

.8.

tion, possibly due to the physiological action of rays

outside the ultra violet region. (Mussehl 1932, 1'2,1:usseh3.

1932 Bethke

Kennsrl and Kick et al. 1929, l'.:1111er Dutcher and Knandel

and Ackerson 1931, 7,,la7erson and Lawrence

3.929),

the common practice has been to re commend some

to 2 of a potent cod liver oil (or its equivalent)

in the rations of crowing chicks (Fox 3.931, Journal of the

American Medical Association, Lditorial 1932, Dunn 1924),

recent experirtenta indicate that under favorable oonditions

such a recommendation may be regarded as quite liberal

3.

(Plirrer ibsedale and ":fx:Trionel 1:)25 Dunn 1924, Gutteridge

1932, Grimm 1932, Halvorson p,nd Lachat 19321, Since It

is nor known that the apparent vitamin D requireMent of

chickens is dapendent upon the levels of calcium and phos

phorus, the Ca/P intake ratio, the 'rate of groT,Tth, and per-

haps other factors, it is easy to understand why different

investizators have obtained variable results with the lar-e

variety of exlnrimental conditions and '.)asal rations used

in such experiments.

in addi ti on to the rachitic le g we akne as due to unfavorable levels of calcium, phosphorus and vitamin D,

there are a number of other leg disorders which 9re not

of a rachitic character, 3ethke and Record (1933) have

classified the various chick disorders as follows:-

Rickets or true leg weakness due to disturbance of

calcium* phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism.

Hock disease, slipped tendon or perosis thought to be

duo to an excess of minerals combined with rapid growth.

Ground whole oats or rice bran appear to possess preventa.

tive properties.

Crazy chidkw bich shows symptoms similar to but appears

not to be identical with those resulting from vitamin

defficiency.

Nutritional paralysis which appears to be asaociuted

with a deficienoy of the vitamin G complex.

6. Ein or fowl paralysis, the nature of which is not

known.

The minimum, optimum and maximum levels of calcium

and phosphorus and the optimum Ca/P ratios recommended by

different workers vary considerably. These variations may

perhaps for the large part be explained by differences

in the rate of growth obtained, the vitamin D content of

the basal rations used, and the frequent attempts to draw

sweepinf, conclusions from experiments limited to a few

weeks duration. A number of investigators have expressed

the opinion that the minimum calcium requirement for growing chicks is about 0.60 and minimum phosphorus, about

0.50 to 0.60 (Wilgus 1931, Tullf,Hauge, Carrick and Rohe

erts 1931* Hart ot al. 1930, Dunn 1924, Cornell 4,xporiment

-10-

Station 13ul1etin 1930), Hart et al. (1930) and tiv Ohio

Experiment Station Annual Report (1920) have suggested 2.0

and 2.5 respectively as thia minimum calcium level, The

Cornell Station Annual Report (1930) caves the optimum

calcium and phosphorus levels as being between 1.0 and 1.2

for calcium and between 0.80 and 0.90 for phosphorus.

Blish and Ackerson (1927) found that 3,02 calcium and 2.15

phosphorus gave good growth but that higher levels WVO

poorer growth. These levels sire probably near a maximum.

Wilgus (1931) reported that 1.2 calcium and 0.50 phosphorus ally° good growths.

For some time it has been commonly assumed that in

mammalian nutrItion the optimum Ca/P intake ratio was of

the order of 1.5 to 2,0 (5stbke at al. 1932

Annual Re-

port, Wisconsin Agricultural .w.z.priment Station 1928-29,

Meigs, Turner at al. 1926, Hart and Steenbock 1930,

Lindsey, Archibald, and Nelson 1931, Reimer and Smuts

1932). Hart, Scott, Kline and Halpin (1930) reported the

optimum Ca/P ratio to probably be between 2 or 3 and 4 and

Bethke at al. (1929) report/3d it to 1-e between 3 and 4.

It will be noted that these ratios are much higher than

those convonly accepted as normal for mammalsiand it should

be pointed out that these investigators used basal rations

which camot be regarded as containing optimum amounts of

vitamins 1), Bart et al. (1930) also observed that an ample

-11-

supply of vitamin D enabled chicks to tolerate wider variations in Ca/P ratios than when the sipply of vitamin D was

at or below the minimum. A number of investigators have

suggested a Ca/P ratio of between 1 and 2 to be better

than higher ratios (Cornell Lxperiment Station 1932, Park

burst and McMurray.1932, Musseba Blish and Ackerson 1927,

Holmes and ?j got 1931, Wilgus 1931, Wisconsin Arricultural

k,xperiment Station 1928-29).' In discussing optimum Ca/P

ratios it is too often assumed that the optimum Ca/P

ratio is a more or less fixed quantity. This is not

necessarily the case. It has been shown by Sherman and

4uinn (1926) and by Haag and Palmer (1928) that young

rats of a certain age store about 1.2 times as much calcium as phosphorus, where, as for older rats, this figure

more nearly approaches 2.0. In the case of Chickens, it

is entirely possible that the optimum Ca/P ratios for different stages of rrowth and for egg production may be entirely

different,

-12THE PROBLEM

As trill be wen from the forgoing literature review,

the calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D requrentents of poul.

try are closely interrelated and these interrelationships

are not as well understood as might be desired. It is not

surprising, thezvfore to find a considerable lack of agree.

merit among various investigators as to the exact calcium,

phosphorus, and vitamin 1) requirements, This lack of agree.

!tient may be explained in terms of a number of interrelated

factors. Attempts to cletermin-,:: tla,3 vitamin 0 requirement

of f'7rowinq chicks have yielded variable results because, as

is now knows Vas vitant.n i) requirement is influenced by the

rate of t7rowth, trv levels of calcium and of phosphorus and

by the Ca/P ratio, The optimum lsvels of calcium and phoshorus are likewise conditioned b7 the suppl7 of vitsrlin D

(or its equivalent). In ad ition to the above factors, there

Is the frequent failure to give proper consideration to the

experimental conditions necessar-: to demonstrate the exact

simifieance of Ca/P ratios,

Tie considerations enurnrated above are not only of

theoretical interest to the nutrition specialist, but of

great practical importance to the poultry industry, This

is especially a r. parent when 713 consider the modern inten-

sive manngernent practices in conjunction with the fact

that excesses of calcium and phosphorus are known to be

detrimental, and that such excesses are apparently net

far removed from the optimum

PROMDUit.

The etperi.ental work described in the following pages

was outlined with the following considerations in mind:

The clloice of basal rations that would moduce an excellent rate of growth under practical conditions.

A study of such levels of °aid.= and phosphorus as

might be presumed to come within the range of optimum

nutrition under practical conditions.

Z.

A study of vitaTran D requirements exid the evaluation

of the vitamin D bearing oils used in the experimental

rations.

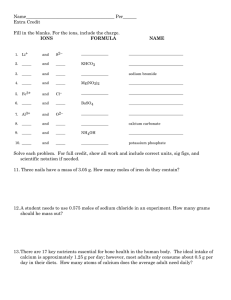

LXII.RIKENTAL keTHO.D5 AND DATA

Three different groups of day old single combed white

legborn chicks (700 in all) were used in these experiments, These were kept indoors in battery brooders in the

absence of direct sunlight« They were weighed weekly.

The chicks were usually divided into lots of twentyi ex-

cept for a few of the oil testing lots.

The composition of the rations used is given in

tables I and II. The rations were of two types. Numbers

147 inclusive were various modifications of the"O.S.A.C«

No. I Milk Nash" formula given in 0.5.A.C. Extension Bulletin 435. In general these modifications dealt with the

amounts of bone meal and oyster-shell flour added to these

rations. Rations 26-29 were also practical rations which

contained less calcium than the "O.S.A.C. no I. Milk Mash"

.14and were made from ingredients obtained from a different

source. Rations 19.26 inclusive were based on the rachit

lc ration developed by the Wisconsin workers. (Hart,Klins

and Keenan 1931). hation and lot numbers are identical

throughout, i.e. ration number 1 was fed to lot number 1.

The cod liver oil used in these experiments was ob.

tamed from a mixed batci of unrefined medicinal cod liver

oil. The sardine oil Was purchased in the ratan markets.

The other ingredients were comnercial products of good

quality.

The feeds were analyzed with the results shown in

Table III. Moisture, ash, crude protein, crude fat and

crude fiber were determined by the A.0.11,C, Method. Calcium was determined by precipitation as the oxalate and

titration with potassium permanganate The oxalate was

precipitated (in the presence of ammonium chloride) from

a solution made red to methyl rod with acetic acid. Phosphorus was precipitated as (NH4)3 4 12 Mo03 and the

yellow precipitate titrated by Fern

Tnetind.

nts alkalimetric

-15Table I.

This table shows the formulas forrations 1,9,10,19

and 30 as fed. Rations 2 to 8 inclusive were made up from

No. 1 as shown in Table fl Rations 11 to 17 inclusive

were made up from "Basal ffier 11.17" as shown in Table II.

Rations 20 to 25 inclusive were rade up from ration No. 19

as shown in Table II. Rations 31 to 33 inclusive were made

up from N. 30 as shown in Table

3a Sal

Nolte Illation

...M11.on_ No.

1

9

10

11-17

19

30

590

400

Yellow Corn

400

400 400

400

Wheat

100

100 100

100

100

Oats

100

100 100

100

100

120

120 120

120

120

Mill

in

Meat Meal

50

50

50

50

Special Low An Meat Meal 50

Fish Meal

Dried Skim Milk

50

50

50

50

50

75

75

75

75

76

Alfalfa Leaf Meal

40

40

40

40

40

5

5

5

5

Sodium Chloride

Ground Oyster Shell

25 10

Precipitated Calcium Carbonate

bone Meal

10

5

25

10

25

26

Precipitated Tri-Calcium Phosphate

5

God Liver Oil

10 10

10

Standard Wheat Middlings

250

Casein

120

10

ta

945 980 960

940

1000

990

-16-

Table II

This table shows the manner in lihich the various rations were compounded from tik basal rations described in

Table I.

=====:

1

Rati,Dns No.

L:,asal for 1-8

3.00

122=111

.

L

2

99.5 99.0

93.0

1.0

2.0

99,0

913.0

97.0

97,0

Cod Liver Oil

Bono Neal

100

0* star '614 1

11

Ration Ne-

Basal for 11-17

Cod Liver 011

Bone Meal

0,.ster Shell

mos*.

Ration No,

12

13

1.0

2.0

3.0

20

14

15

16

.17

98.5 96.75 96.50 96.00 96.50 94,50

0.5 1.5 0.25 0.50 1.0 0.50 0.50

2.00 2.50

99,5

10

20

30

30

21

22

30

1.002.50

4.========

24

23

25

Basel for 19-25 100 99,875 99,75 99,5 :)9.6759.75 99.50

0.125 0.25 0,5

Cod Liver Oil

0

Sard1ne_011

Ration No.

Basal for 26-2'4*

Sardine Oil

Cod Liver Oil

====t-mh.._

Ration No.

Basal for 30.33

Sardine 011

26

100

27

28

29

99,75 99.50 99.75

0.25

0.50

0.25

_j2p

31

32

33

100 99.875 99.75 99.50

0.125

*Rations 26 and 30 were made up without any oil.

0.25 0.50

Tilble III

Chemical Analyses of Rations

Ration Mois. Ash

ture

No

Ca

Ca

Nx6.25

2

10.93 4.37 0.64 0.66 1.0 18.75

11.45 4.35 0.67 0.67 1,0

3

11.60

4

11.31 5,66 1.13 0,87

10.86 5.17 1.02 0.66

1

5

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

26

30*

5.48 1.43 0.66

10.30 6.17 1.75 0.65

10.75 6.28 1.63 0.75

10.75 8.06 2.60 1.03

10.07 5.95 1.52 0.85

10.23 5.23 0.86 0.74

10.06 5.83 1,25 0.73

9.83 7.19 2.07 0.72

9.90 7.00 2.09 0.72

10.23 7,27 2.12 0.70

9.89 7.20 1,78 0.95

9.50 8.36 2.43 1.00

11.32 4.57 0.79 0,66

10.13 7,70 2.16 1005

011 00 WI

410111111111111111001i=111141111111111111111101111

5.12

Fiber

3.30

5,48

5.08 0.88 0,77 1.1

10.81

6

fat

WOOM

WIMP4mh

Woo.*

1.3

1.5

2.2

2.7

2.2

2.5

4.96

3.60

1.2 18.96

1.7

2.9

2.9

3.0

1.9

2.4

1.2 19.34

4.52

4.97

4,44

4.39

5.45

3.95

2.1

15.40

3.94

4.66

WOOVIN

0.000M

41001...

411WOOM

18

4.94

5.09

2.16

* Ration No. 30 as 3iri1ftr to R-,,tions 9 and 17, except for

oil levels.

-18-

The chickse were bled from the heart and the total

calciun enc1 inerefe-lic eboseheres of the blood serum were

t1::

are :elven in table VII,

n.

i e i

4bL

c 117 s

ro,iment, the chicks were

killed en1.1 the lee, bones eeeoeed, he right tibia tyas

exaelined eeistoleeicalle aria than crushes, dried, extracted

with hot alcohol aree then eith ether, The bones were then

ashed for eix hours at 7000 C. and the ash expressed on

the dry t free basis.

For lots 19-25 (start,ed. ene. 6) the right tibias were

lashed individually an the resats averaged. For each of

theee lote, totel nointuee and fat free bone weights were

divided b":.7 total e sh woiehts ehe results of these eelculee see e

de te

ations re re co re d. -with the evorages of individual ash

percentages, e coeperieen was thus obtained between the

results ee ineivieuel eshine an' the results which would

have beee eete. 1. Teel if !r1.11 the beees of each lot had been

grow-el,

eel() e !lee

ee pre se nte tive sari ple a 81-..,e

The cliff -

erenceci eetween the tee metheis vere not sienificant

showia in table I; I, The ma tho of .eroup lashing by the lot

was useee for al 1 other :cieht tibia ashines,

vibe eri ter wishes to cern() rae dee his in de bte dne s s to

Johnec,e, eoultre Petheleeist, Aeric71.1tural e;xper-

iment :jeation, Orton Stet eolloee, for his service in

bite ding the ceicks from the rt rt and for examinine them

for abnormalitieS

.19.

Table IV

Chick weights (grams) and 7!orta1ity. "Average" weights at

5-13 weeks 10 Amtml4LIT9,9_221Anct 4 average female weight.

2

allIO4r.em

Lot ito. No

t

"Orig.Av

CI-11 cks

thai

t

1117.IA.

Av.Yrt..

AvOt

-----"r--Zr-,

34.65 552

530

1

20

4

2

20

3

3

20

4

4

20

2

5

20

6

a,

34.55 346

34.55 357

7:757-rff wks. 13 wks.

964

1060

518

927

1034

640

980

1093

528

933

1045

3

34.2 548

34.55 352

547

932

1042

20

5

34.20 356

505

927

1052

7

20

2

34.65 338

490

897

1017

8

20

8

653

954

1083

9

20

4

34.40 361

34.45 409

623

1051

1171

10

19

1

31.00

555

957

1049

350

32,6 413

727

12

21

4

33.0 468

791

13

21

4

33.6 427

711

4

14

21

32.1 427

731

15

21

0

32.4 412

725

16

3.

21

32.6 416

730

17

21

33.8 404

726

* The relatively high mo rtali ty is lk rm. 1 y due to deaths

rs sui ting from taking bloc d sun pie s from the art.

11

21

3

Table IV continued

No. of

chicks

Lot No.

19 (Started June 10)

oria1-3rity

12

0

20

ft

ft

11

0

21

ft

ft

11

1

22

n

ft

11

0

11

0

11

0

11

1

20

1

23

24

ft

25

n

ft

19 (Started Aug. 6)

21

ft

It

20

0

22

ft

ft

20

1

24

It

ft

20

0

If

If

20

0

26

12

0

2'7

10

2

28

10

0

29

10

1

30

20

3

31

20

32

33

25

ft

wt

w s.

33.4

35.2

145

32.8

32.5

34.0

32.8

32.5

33.7

35.6

33.5

33.8

33.8

193

34.2

32.5

32.6

192

270

161

274

330

174

231

260

232

269

8 wks.

502

559

589

588

1

33.4

33.8

33.9

531

648

20

2

34.0

503

618

20

2

34.0

639

755

512

9 wks.

623

.21.

Table V.

Bone data obtained from right tibiae.

Lot No.

Age in

;4) Ash*

emarks

weeks

1

13

2

13

48.8

50.1

3

13

50.6

4

13

52.4

5

13

50.5

6

13

7

13

51.4

51.9

8

13

9

13

10

13

11

9

12

9

13

9

14

9

18

9

16

9

17

9

52.2

53.3

53.4

52.6

Approx. 30% slipped tendons.

49.8

47.2

49.5

50.6

50.1

50.6

*The "% ash" figures given in Table V were obtained from

composite samplas prepared from the right tibiae.

4.22.

Table VI

Bone data obtained from right tibiae

Age in % Ash % Ash (Av. of

weeks (Composite Individual

Lot No,

Sample)

Remarks

bork,$)

19 (June 10) 5

31.1

all rachitic

6 rachitic

3 rachitio

0 rachitic

9 rachitic

3 rachitio

0 rachitio

20

ft

5

35.9

21

ft

5

40.8

22

5

44.9

23

5

34.3

5

40.1

25

5

19 (Aug.6)

5

24

ft

21

tt

5

45.6

(50.7)

(39.4)

22

a

5

(43.3)

5

(3864)

5

(42.9)

42.5

48.3

48.3

48.0

24

25

a

26

8

27

8

28

8

29

8

30

9

31

9

42.7

46.5

32

9

47.4

9

49.6

50.6

all rachitio

39.2

43.3

?!. rachitio

38.0

42.8

Normal

13 out of 20 rachitic

1 out of 20 rachitic

1 rachitio

0 rachitic

0 rachitic

0 rachitic

all rachitio

7 out of 19 rachitic

14 normal: question

about 4

Normal

-23Table VI continued

The it% ash" values given in table VI are of 3 types.

The firruzes in the third column, not in parentheses, were

obtained by ogling composite samples. Those in the fourth

column are group averawes obtained by averaging the ash

content of individual bones. Those in parentheses in the

third column are calculated to the composite basis from the

data obtained from the individual bones, %marks on lots

25 (June 10) and lots 26 - 29 are based on appear19

ance of chicks during 5th week. Remarks on other lots are

based on examination of tibiae.

-24Table VII

Blood analyses based on composite samples drawn from heart.

Analyses are expressed in mm., pr 100 cc, of serum.

Age of chicks

Lot No.

w

mon,

Days

Inorganic

Calcium

sartWa_j2,)j)d

or 100 cc

9.72

Phosphorus

Infrn1

per 100 cc.

1

51.554.69.90

2

ft

tt

It

tt

9.79

7.16

7.28

3

It

ft

ft

If

10.01

6.29

4

tt

ft

ft

It

10.41

5

If

II

It

If

10.48

tt

ft

tt

10.27

7.38

6.69

6.48

5.16

6.51

6.46

6.66

6.12

6.18

6.81

6.68

6.67

6

7

ft

ft

ft

II

10.40

8

11

It

tt

It

10.23

9

It

ft

n

ft

10.23

10

11

ft

ft

II

ft

10.37

68

12

ft

13

ft

14

ft

15

ft

16

ft

17

ft

30

66

31

ft

32

33

ts

9.79

9.58

11.99

12.58

7.27

7.17

6.18

7.81

7.43

7.34

.25.

The rate of growth obtained in these experiments was

comparable to that obtained in actual practice. The r,rowth

and mortality records are summarized in table Iv. The

weights are given at ages which allow comparison with other

studies. The somewhat more rapid growth of lots 9 and 10

over lots 1 - 8 inclusive was probably due to the superior

quality protein of the meat meal used in rations 9 and 10.

The apparently high mortality in some groups is largely

due to deaths resulting from the taking of blood samples

from the heart for analysis. There were no indications

that nutritional factors wore involved in mortality rates.

Tables V and VI contain a summary of the ash of the

right tibia, results of the histological examination of the

bone and comments based on anexamination of the chickens.

DISCUSSION

In romnal, satisfactory growth was obtained throughout the experiment on all the practical rations. This is

of considerable significance because some of the variable

conclusions arrived at by some other investigators are un.

doubtedly influenced b7 the relatively poor growth ob.

tamed under certain experimental conditions, It may be

assumed that the requirements for at least certain nutrients

are considerably areater where rapid arowth is obtained.

Our results should therefore have some application in

actual practice.

.26.

A summary of the more important data is given in

Table VIII.

In general the growth, blood analyses and bone ash

data do not favor either the higher calcium and phosphorus levels or higher Ca/P ratios. The calcium and

phorus levels of lots 9 and 17 may be consider, d as being

near the maximum for these elements since slipped tendons

were produced in lot 9. There is some indication thatthe

Ca/P ratio of lot 7 was exceesive.in view of the slightly

slower rate of growth and the continued lower level of

inorganic blood phosphorus.

Tho good growth of the

chickens on all of the lower cab? ratios does not indicate

that the optimum Ga/P ratio for chicks is vastly different

lower bone ash for

lots one and two would seem to indicate that the calcium

and phosphorus levels of these rations were approaching a

than that for mammals. The all

In lots 1.17

the higher mineral levels seemed to give slightly higher

minimum, although rood growth was obtained.

bone ash figures.

The particular lots of sardine and medicinal cod

liver oil used in those experiments seemed to be approximately equal in anti rachitic potenc-, as shown by the

bone ash figures for lots 19 to 25 inclusive. The lower

vitamin levels in lots 30 and 31 may have caused a slight

depression in the blood calcium of these lots.

-27-

Table VIII

Summary from Tables 1-VI.

Lot

No.

1

Vitamin D

Ca

6earing oils Ca

.5:* C.L.0.. .64

1)

P

.66

1.0

"Average"

reirtht

(7ra7s)

13 wk.

bone

ash

1060

13 was.

48.8

n

ty

ft

.67

.67

1.0

1034

50,1

3

.52% "

ft

ft

.88

.77

1.1

1093

50,6

4

.52% " "

tt

1.13

.87

1.3

1045

52.4

5

.52% "

tt

IT

1.02

.66

1.5

1042

50.5

6

.52% "

ti n

1,43

.66

2.2

1052

51.4

7

.51% "

It

n

1.75

.65

2.7

1017

51.9

8

.51% " n

n

1.63

.75

2.2

1083

52.2

2

1.03%

9

1,02% "

ft

n

2.60 1.03 2.5

1171

53.3

10

1.04% "

fl

n

1.52

1.8

1049

53.4

.85

1,2

729

9 reeks

52.6

1.25

.73 1.7

791

49.8

II

2,07

.72

2.9

711

47.2

ft

ii

2.09

.72

2.9

731

49.5

II

ft

2.12

.70

3.0

725

50.6

16

.50% " " 0

1.78

.95

1.9

730

50.1

17

.50% "

2,43 1.00 2.4

723

50.6

1110111.01.10111............101111.0...apoomeMMONO.....1-

11

*50% "

II

.86

12

.50% " " "

13

.25% "

ft

14

.50%

ft

15

1.00% "

tt

tT

It

9 weeks

.74

Table VIII Continued

Lot, -ftamin

_0, aearing oils

Ca

2

'Average"

eight

(Grams)

o veeks

WeeKS

19

none

20

.125

C.1,4004,

192

31.1

35.9

21

.25

C.L.O.

193

40.8

22

.50

C.L.O.

270

44.9

23

.12b,b' S rdine oil

161

24

.25%

"

25

.50

H

19

none

21

.25% C0L.041

2.11

22

50% "

260

24

.25>, Sardine oil

25

.50%

.79

.66

1.2

145

ti

274

34.3

40.1

it

330

45.6

174

30.6

39.2

43.3

.79

.66

1,2

"

ft

232

269

8 wES

38.0

42.8

8 weeks

502

42.3

27

2.16 1.05 2.1

.25% Sardine oil

559

28

.50%

589

29

4,25

48.3

48.3

48.0

30

none

31

.l25;

26

none

32

33

.50%

"

588

C.L.O.

9 weag

oil

648

46.5

618

47.4

755

49.6

In view of the relatively large number of factors involved, it is not possible to state the exact requirement

for calcium and phosphorus. The following statements, how-

ever, appear justified:

These studies show that excellent growth can be obtained on levels of calcium and phosphorus considerably

lower than those commonly recommendad.

There is no evidence in these studies to indicate that

Ca/P ratios for growng chicks are essentially different

wth of other

from those considered optimum for the

animals.

These studies indicate that if prevailing recom nda

tions for calcium and phosphorus are to be mvieed, such

revision will probably favor lower, rather than higher

calcium and phosphorus levels.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

1. 700 chicks were fed practical mad experimental rations

containing various levels of calcium, phosphorus and vitamin

D.

The medicinal mid liver oil stock and sardine oil used

were shown to ha Na essentially equal antirachitic value.

3. Satisfactory levels of growth were obtained on all

practical rations used and results should therefore be

applicable to actual practice.

2,

Growth, blood analyses, and bone ash data in general

do not favor the high levels of calcium and phosphorus

or of Ca/P ratios often advocated.

5. The results obtained do riot indicate that the optimum

Ca/P intake ratio tbr growing chicks is vastly different

from that considered optimum for riannale

'IOGRAPHY

Asmundson, U.S., Allerdyce, 1J,, diely J. (1929) poultry.

Fish oils as sources of vitamin D for

irr. (Canada) 9 p. 594

Bethke, Rolle, Kennard, D.C. and edck, C.H. (1929)

The availability of calcium in calcium salts

and minerals for bone formation ir the growing

chick.

Poultry Sc., 9 pp. 45-50

aeth

Bethke,

H.M., Kennard, D.C., dick, C.H., Zinzalian,G,(1929)

The calcium-phosphorus relationship in the

nutrition of the illiowing chick,

Poultry Sc., 9 pf:), 257-265.

KiCL:,

C.11. Vilder,

(1932)

The effect of the calcium-phosphorus re1tionship or r,rowth, cvlcifiction and blood com-

position of the rat.

J. J31o1. Chem. 98, pp. 359-403.

Liethke, h.". hecord, P.h., (1433)

it disorders of prowinr chicks.

Sta. .:imont 17

Ohio ir"ricultulel

,ol.

III,

asthke, H.. (1930)

p. 46-0.

tlation af tha calcium-phospiaorus

ratio to calcificPtion.

OL:do

1111. 446, r. 147

3ill s,

C.12,.*

-xo. 3t. 48th A nun].

pt.

(1927) ,ntirachitic sstances,

iP

VI the dis-

tribution of vitanin D -1th sone notes on

its possiblo origin.

J. LA01. Cher,. p:. 751-6.

130

J., McKittrick, -.J. (1923)

Studies in inorganic netabolism. I - Interrelations between cslcium and magnesium

metabolism.

J. Biol, Chem. 54, Pp. 363-374.

3rown, D.3,, Shohl, A.T., Chapman,

Rose, Ca.,

Saurwein L.W. (1932). Rickets in Rats. XIIIThe effect of various levels and ratios Of

calcium to phosphorus in the diet upon the

production of ricKets.

J. 3io1. Cbem. 96, PP. 207-214.

Buckner, 6.0.11, Martin J.h., and Isko, V.M. Jr. (192)

Effect of magnesium carbonate when added to

diets of growing chicks.

Poultry Sot. 11, pp. 58-62.

ftngel C., Textbook of Physiological 8nd Pathological Chemistry. 2nd Eng. Editio, 2, Jlakeston 31on & Co.,

Tthila. 1902, pp. 82-10;.).

3urnett, T.C. (1406), On the ;)roduction of glycosuria

in rabbits by the intravenous injection of sea

rater made isotonic vith the blood.

J. J101. cLdem. 40 pp. 57-62,

Dunn, L.C., (1)24), The effect of cod liver oil in various

'

amounts and forms on the growth of 7ounr chickens.

J. iio1 them. 610 pp. 129-136,

Editorial, (1932), The relative efficiency of vitamin

preparations, in dia.Terent species*

J. Air. Med. Ass'n. 99, pp. 565.6,

Elliot, Nelson, 3Outhy, Cr".ft (1932). The value of salmon oil in the trea-ment of infantile rickets.

J. Am, Mods Ass'n. 99, pp. 1075-82.

Steenbock h. (1929) Calcium and magnesium

Elmsbil,

relations in the animal.

J Biol. Chem. 82, pp. 611-632.

Forbes,

(1924) Mineral nutrient requirements of farm

animal J,

National Research Council. Reprint and Circular

Series No. 60, pp. 1-12.

Schtliz,

Hunt,

Vinter,

Remler. (1922) The rineral metabolism of the

mulch cow.

Ste. jul 363, pp, 1-69.

Ohio A7r.

:cox, i.U. (1931) Chick

Forboo,

Oregon stet-) r -r. Col1e7e -Nt. :40rvice

tat. r3u1, 435,

(192), Report on bio1or1c81 rrothods for the

determination of cod liver oil in feed mixtures.

J. of A. of Off.

7T. 222-26.

Gutteridge, M.S. (1932n), Vit8,-11n A and D studies with

growin7 chicks.

Chem. 1F'.1

Sol. :irrr. 12, po, 327-37,

Gutteridge H.S. (1932), Pilchr,rd oil as a supplementary

feed for young chicks. Seasonable hints.

The Dominion .L',.xport-ental 1rm3.

55

-Prerie £ditior, pp. 12-13.

Haag, J.A. (1926), The antagonism of mineral ions in

animal nutrition.

Doctor's thesis, U. of 0inni.

19a;.

hivT, j.R., Pnimer, L.S. (1928), The effect of variations

in the proportion of calcium, magnesium, and

phosphorus contained in the diet.

J. biol. Uthem. 76, pp. 367-389.

Kin,

(1931) Calcium-phosphorus metabol..

ism in the chicken. I. The effect of irradiated

ergosterol.

Hall,

Poultry Sc., 100 p7). 132.153.

Halvors.:n h,A., Lachat, L.L. (19?,0, Control testing of

fish oils for vitamin .0 content.

Sate of

Dept. A-r. Dairy anci Food.

Halvorson, H.A., Lachat, L.L. (1932a) Flour and eed.

pp. 8-10*

liarrar, N.J. (1925), The theory of salt craving.

J. Chell. _Jducation

Lialpin, J.C., 3teenboci-c, ki., Johnson, 0.N.

Black, A. (1922) Nutritional requirements of

baby chicks, II Further studies of leg weakness

in chickens.

J. Biol. Chem. 52, pp, 379-36-.

Kline, 0.L., Koonno J.. (19:51), ration

for the production of rickets in chicks.

3ci, 73, pp. 710-11.

Hart,

hart,

Hart,

Hart,

T:p. 1054-1058.

F=

,

3teenoock,

humphrey, U.C.,

(1911), ' ilysiological effect on rrowth and re.

TcCollum,

production of ratio,ns halr;nced fl'om restricted

sources.

Wis. Agri. Lxp. 6ta. 23th in. Rept., pp. 131-205.

Scott,

Q.L., Halpin, J.G. (1930),

The calcium phosphorus ratio in the -,itrition

of growing chi &so

Poultry Scis 9, PP. 296406

4.34-

Hart,

.B., Steenbocks H. (1911)s The effect of hiFh magnesium intake and calcium excretion by pigs.

J. diol. Gher. 20 p.

narts

hart,

Steenbocks

(1913)s

effect of a hi7h magnesium intake on calcium natention b- swine.

{2;

.

L.

ilert, 11.

J. 31°1. Lhe, 14, pr). 75-a0.

Steenbock L.St al. (190) Dietary factors

influencing calcium assimilation XIII 11;le

influence of irradiated yeast on the calcium

and phosphorus metabolism of milkinrr cows,

J. 3101. Lthem, 86, pp. 148-355,

Steenhocks Cixi8oL,

0_43)

mineral

feed proble in

!Ise,

&90. Jan. 1917.

Pigl7ots

C'.

(1931), The effect of cod liver

oil on calciu7,-,1 metabolism of yourip chlcks.

Ind. &

Ghe,,, 25. p 190.

HI:tffmans

Abbinson,

7inter, 0,1),s Larson,

(1930)s The effect of 1o7 calcium high magnosimm diets on rrrowth and metabolism of calves.

t_Ce Journal of .Lultrit1ci Ps pp 471483,

Idaho, Agr. xp. Station, (1929), hxperiments with poultry

at tie Idaho 3tmt1on. 0o. 164, pp. 3739.

Eall0

(1X31), "L;lcium

phosporus

abolism in the chicken III - Influence of cereals

and vitamins A and D.

Poultry 3ci. 10, PP.

Linase7, J.B., P.rchibald0 J.G., Nelson,

0.931).

rfix; calcium rvuirements of dairy heifers.

J. Agr, tieser6ch 420

pp. 863.896,

Loeb, J. (1916), The Or-anism as a whole,

0.P. kAltrAFnts sons, h.7. 1916, pl. 306-317,

!7cColluris

(192±:),

influence of the composition ud arnunt of the mineral cotent of the

ration on 7roth Ind reproduction.

J,

21, pp. b1FS-C44,

VcCollums

Simmondss

hiple7, e.G Vark A,

(1921), Studies on experimental rickets.

Tic production of rickets by diets

low in phosphorus and fat-solubl

J. Aol, Con. 47,

pp, 507-270

Massengile, 0.N# Nussmeier, M., (1930), The action of acti-

vated ergostarol in the chicken.

J. Biol. Chem, 87,pp. 415-426.

4ods30 G, (1926), Magnesium metabolism on purified diets.

J. io1. Chem. 68, pp. 295..316.

rdirlp.,, T.5., iiartman A.M,

Turner, W.A.,

Meigs,

(1926), Calcium and phosphorus

Grant,

metabolism in dairy cows.

J. of r. Aes. XXXII, pp. 833.860.

(1909), Me excretion of

n7indel, L.3.,

magn,:Jnium and calcirm.

J. A.ol. cA)m.. 6, p. 20.

TI

(1J23a), otassiuTrt in nnil nutrition.

2otasivi:71 in .t.s relation to tiie

of 7ounF rats.

,T, iol.C.Lcr3.0.56,2p. 61-73.

(1926), Potassium in animal nutrition,

III influence of potassium on total excretion

of sodium, chlorine, calcium and phosphorus.

J. Biol. Chem. 69, Pp. 71-.770

iiI r,

(1923), Potassium in animal tiutrition.

I Infimnee cf pota3Aum on urinar sodium

and chlorine excretion.

J. 1o1. ken. t5, p. 45-59.

Dutelmr, A.a. Knandel LL.C (1929)0

I4utritional leg-weakness in poultry.

1jou1tr: 1ci.

pp. 113125.

Roche. A., (1931).

Yoriquand, G., Leulier,

Magnesium and experimental rickets.

6oc. jiol. 191, 107, pp. 676-677.

Pat. Abs. & Rev. Vol. 1, p 83. 1931.

Ackerso, G.V. (1930), Irradivted errtolterol

as an antirachitic for cA.cks.

Poultr:

9, PP. 334-3.

j. cerson, (;00 (13)2), L=,ffeet of rodif

russehl,

inr the ca-e r&tio 7,)f specific ration for

frowin

f'o7ltr '2Z1. 11, pp. 293.6.

gussehl,

Ackerson, C.'v4., (1927),

Mineral Metabolism of the growing chick.

Poultry 0i 6: PP. 29-242.

Mussehl, FIDi' 111414 a.F.,1is, 71.J. i'ickerson,

(1930)

The utilization of calcium by the growing chick.

J. Agr. 193 400 Pp. 191-99.

Needham, Joseph, (1931), Chemical Embryology*

Nelson,

Cambridge at the U. press. p. 18180

.M., Manning, J.R., (1930), Vitarrdn A and D in

fish oils.

Ind. A-ng. Chem. 22, pp. 1561.3.

Poultr7 Studies at the 14,7,ornoi1 Stption, (1930)

Annual Aeport i,Y, Gornell

pp. B8-910

Ohio Agr. hxp. Sta. 46th !lual fteport. (1)23).

,jul. 417, p* 65.

:-(ridol, L.3., (1913), The inorganic elements

J. 40. Chem* 34, pp. 131..14().

Parkhurst, R.I., McMurray, M.t. (1932), The relation of

Calcium and Phosphorus to -rov4th nd rachitic

leg we

in chickens.

Sci. 22, on. B74-32.

J.

Plinner, (blirAssl Hoselale, J.L. ia7nond, V.;.tj (1925).

vitni71 re qirenent of cl.lckens.

Aachen. J. 21, pp. 940-4.

Smuts, D.3., (1932).

Reimers,

The significance of calcium and phosphorus in

the development anri growth of .rAgs.

Arch. f. TiersrAtihrung

Tierzuct. 1932.

7: PP. 471-531.

Fro,

Ahs.

2 r. 411, (1932).

rtinrer, S. (1880-82). Concerning the influence exerted by

each of the constituents of the blood on the

Osbo-Lnl,

in nutrition.

contraction of the ventricle.

J. Physiol. 3, pp. 280-92.

(1362-1b3), h furtiAjr contribution -regarding the

1.1fInence of the different constituents of the

blood on the eontraction of the heart.

Ringer,

J. ?h7siol. 4, pp. 29-42.

Anger, S. (1992-1353-a), third contribution regarding

tle influence of te inorganic constituents of

the blood on the ventrienlar contr ction.

J. :Th78101, 4, pp. 222.45.

Anger, S. (1336)* Further experiments regardin, the influence of srall ,?uantities of lime, potassinm

on muscular tissue.

and other

J. Phs1ol, 7, pp. 291-306.

Robertson,

1.. (1920), :14inei les of 6-lochern1stry.

Lea and Febimor (L'hila 1920), pp. 263-271* ;AO-

n7.

Russel,

c0.0

(1931),

cyA.tr7: sci. 10,

Shrman,

r.i):3

vitamin

content

of a ration and the antirachitic potency of

irradiated ergosterol.

269-74.

.C. (1962), The chemistr:i of foods and nutritions.

Nio/ ';ork- The Yacmillan Co., p. 243.

Pananheimer,

(1921), ilxperirlental

rickts in rats 1 - kl diet producing rickets in

white -fats, and ita 7rovention by the adlition

of an inorgahic salt.

T. .Lxote. Med. t.i

o 139-93.

B.C., 4iuJ_nn, .L..J.(1926), he phosphorus content

of the body in relation to age, ,,rowth and food.

J. A.ol. Chem. 67, pp. 667-6770

Sollman, I:, (1924.) A rannal -f p1rrnacalog7.

')aunders tz Cc. _hila. p?. 741-953.

Steenbock, H.,

S,J.* ,alpin, (1932).

Tho rection of the cicken to irradiated errosterol and irradiated east as contrasted pith

the natural vitamin 0 of fish liver oils.

J. ioi. (hew.. 97,

249-264,

Tolle, C.i), aelsn,

(1931), Salmon oil and canned

salmon PS sources of vitamL A L-tnd D.

Ind. &

Cem. 23, pp. 1066-1069.

Truesdail, R,W, Culbertson, H.J. (1)33), Sardine and tuna

oils as sources of vitamin D,

In. 4_,n7. Chem, 25, p. 563.4.

Tull:,

Eague, S.M., Carrick, 0,,,obeite,A,:z.,(1961)

Calcim and phosphorus reimirements for growing chicks I - studies wit -alt mixtures under

rachitic conditions.

Ponitr.: Selo 10, pp. 29.4f109.

W-neeler$ !7.?. (1919) y a:rle stoldies relatin7 to cslCium

Metabolism,

-xn.

i.Geneva :all. t463,

(1:.431), Thu iititcitie ruirement of

"3*

'

f-yowin!7.., chick for calcium and phosphcrus.

: 07.11tr7 2ci, 10, pp. 107-117,

A.sconoin, Apr. .L.-xp. Sta. dew 6cionce for an old art.

ort, 1928-29.

410, 1,eb, 1930, p, 73-4,

.37.tnurkl

A/1