Walking the Talk: Human Rights, Access to Justice and the... Poverty Dan Banik

advertisement

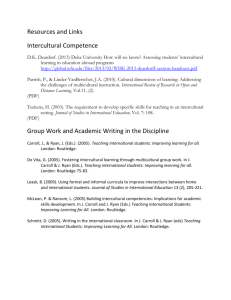

Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) Walking the Talk: Human Rights, Access to Justice and the Fight against Poverty Dan Banik INTRODUCTION The past couple of decades have witnessed growing interest in linking poverty reduction efforts with improved access to justice. With the UN Millennium Declaration (2000), world leaders appeared to endorse the idea that the abolition of poverty was in reality a matter of international redistributive justice. And 189 countries reaffirmed their commitment to do their utmost to help individuals and groups facing ‘the abject and dehumanizing conditions of extreme poverty’ and committed themselves ‘to making the right to development a reality for everyone and to freeing the entire human race from want’.1 Thus, numerous scholars, international agencies and aid practitioners began to advocate in the 1990s, a closer linkage between human rights and economic development. They claimed that a human rights focus ensures that the developmental process is correct, both morally and legally, and helps build stronger national and local institutions based on genuine social mobilisation and accountability. Some argued that the human rights-development linkage forces development practitioners to confront the tough questions of their work: matters of power and politics, exclusion and discrimination, structure and policy (Uvin 2004). Others argued that the astonishingly high levels of global poverty required revisiting its root causes, including the role of affluent nations. Accordingly, the existence of poverty in a 1 http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm 1 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) world of plenty, they argued, such be viewed as a ‘violation of human rights’ (Sengupta 2005; Pogge 2005). Two approaches in particular – the human rights-based approach to development (HRBA) and the legal empowerment of the poor (LEP) – have been promoted and applied by a set of international, national and local organisations in their attempt to promote development and combat poverty. These approaches aim at reforming conventional (needs-based) developmental efforts, which are criticised for treating the poor as passive receipts of welfare rather than active participants and agents of change. With an emphasis on respecting, protecting and promoting the human rights of people living in poverty, these approaches have focused attention on the actual process and means of development, which they argue should aim to empower marginalised individuals and groups to participate in decision-making and holding powerholders to account. By comparison, they argue, that conventional development strategies have failed to substantially reduce poverty as they have been excessively concerned only with the end results. Despite their obvious merits, both HRBA and LEP have been labelled by their critics as appealing buzzwords that give the impression of radical change but delivery very little in practice. The increased frequency and ease with which HRBA and LEP have been used by various agencies, has also been criticised for betraying the complex challenges that thwart the realization of basic human rights for people living in poverty. And the constant desire to introduce new terms and approaches has not only flooded the development discourse with jargon that is difficult, if not impossible, to operationalise, but scholars and activists around the 2 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) world worry that there is limited empirical evidence available to suggest that such concepts are being rigorously applied by those who are responsible for designing and implementing aid-driven development programmes. Critics thus argue that behind the scenes lies a multitude of voices, interests and perspectives that draw upon very different conceptual understandings of poverty, rights, and the relationship between the two. I begin this essay by briefly and critically discussing the main features of the HRBA and LEP approaches in relation to development and poverty reduction. There is now a growing volume of literature on the difficulties of operationalising these approaches. My aim is the opposite. I wish to identify and highlight a set of efforts by a wide range of actors at national and local levels using key elements of the HRBA and LEP that yielded numerous positive results. Thus the empirical focus here is on various initiatives that are aimed to promote the right to food in India. These include a series of petitions handled by the Indian judiciary starting in the mid-1980s that brought national attention to the persistence of extreme hunger and starvation deaths in many parts of the country, and the role and duties of national and regional governments to provide adequate assistance to households vulnerable to hunger. While the initial verdicts by the courts in the late 1980s and early 1990s generated considerable media interest on the issue of undernutrition and starvation, the ensuing recommendations of the judiciary were largely ignored by the political and administrative leadership at both central and state levels. By comparison, I also examine the basic conceptual frameworks of the LEP and HRBA approaches in light of an on-going case on the right to food in 3 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) the Indian judicial system, which has been championed by civil society organisations and that – despite the awaited final verdict – has resulted in significant and positive changes in policies and programmes on food policy in the country. The overall aim of this essay is to identify the conditions under which human rights-based and legal empowerment approaches can be useful in promoting the access to justice of people living in poverty. PART 1 HUMAN RIGHTS AND LEGAL EMPOWERMENT FOR POVERTY REDUCTION The development discourse in the past couple of decades has witnessed growing interest in viewing poverty through a human rights lens. This has largely corresponded with the increased frustration and impatience over the ability of conventional ‘needs-based’ or ‘economic growth-based’ developmental approaches to deliver quick and long-lasting impacts on poverty reduction in large parts of the globe. Since the 1990s, various attempts have been made to articulate what a human rights-based approach to development (HRBA) actually means. Given the involvement of a wide variety of development actors, organisations and academic disciplines, the HRBA has appeared to be a broad collection of ideas and practice centred on a set of core human rights principles. These include participation of the poor in decision-making, and ensuring that state and non-state actors are aware of the importance of, and practice, social inclusion, nondiscrimination and enhanced accountability of power-holders in the discharge of 4 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) their duties. Hence, there is now general acceptance of the idea that conceptually the HRBA entails a process of human development that is normatively based on international human rights standards and operationally aimed at promoting and protecting human rights (OHCHR 2006). The main value added of the HRBA, according to its supporters, is that the approach creates claims and not charity (Uvin 2004, 129) and that it promotes the sustainability of development work by empowering marginalised peoples with the ability to ‘participate in policy formulations and to hold accountable those who have a duty to act’ (OHCHR 2006). At the same time, the universality of human rights is highlighted, in addition to the principle of ‘progressive realisation’ of rights in development, which means that given resource constraints, not all problems of all people must be tackled at once. One of the early supporters of the HRBA and a former senior official of UNICEF, argues that human rights are important (and differ from conventional need-based approaches) because they represent specific relationships between individuals (who have valid claims) and others (e.g. individuals, groups or institutions) that possess the duty to respect, protect and fulfil human rights (Jonsson 2003). And ‘Except for very young children, all individuals have both valid claims (rights) and duties’ (Ibid: 16). By comparison, development approaches that emphasise basic needs do not recognise the idea of a duty bearer, with the result that no one has a clear-cut responsibility to meet the needs of the poor and protect their rights. Within the HRBA framework, the poor do not lose their rights when they are incapable of claiming them (fulfilment of rights may be 5 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) compromised), as human rights are considered universal, inviolable and inalienable. The HRBA consequently emphasises the principle of equality in that community resources must be shared equally ensuring that access to various services are enjoyed by all. By comparison, the basic needs approach often tends to place greater emphasis on acquiring additional resources to improve the access that marginalised groups in the population have to various basic services. Thus, while conventional development approaches do not necessarily recognise ‘wilful or historical marginalisation, a human rights approach aims directly at overcoming such marginalisation’ by getting more actively involved in the political discourse on such issues (Ibid, 20). When examined in relation to conventional need-based approaches, the HRBA also differs with respect to its emphasis on the process of development and the manner in which development policies are implemented. In other words, ‘the means, the processes, are different, even if many of the goals remain the same’ (Uvin 2004, 129). While basic needs can often be met through ‘benevolent and charitable actions’, the HRBA is based on ‘legal and moral obligations to carry out a duty that will permit a subject to enjoy her of his right’ (Jonsson 2003, 20). And this implies that a duty bearer must accept the responsibility of taking rightful action and be motivated by a desire to promote justice, features that is negated by the basic needs approach’s emphasis on charity and benevolence (ibid., 20, 21). Based on the above two sets of issues, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR 2006) argues that human rights 6 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) ‘contribute to human development by guaranteeing a protected space where the elite cannot monopolize development processes, policies and programmes’. Moreover, by linking human rights to development, development practitioners are in a better position to confront and address issues of unequal power relations in local society, and the politics and practice of exclusion and discrimination (Uvin 2004). Others have argued that the continuation of world poverty should be viewed as a violation of human rights, and by doing so public action can be mobilized against the governments of democratic countries for the adoption of more pro-poor policies (Sengupta 2005; Pogge 2005). In practice, the HRBA has been variously used by international agencies and civil society organisations. These include as a set of normative tools on which development strategies are based; as a set of instruments with which to develop assessments, checklists and indicators against which interventions can be assessed; as a component to be integrated into programming; and as the underlying justification for interventions aimed at strengthening governance and institutions (Nyamu-Musembi and Cornwall 2004). Although the HRBA was gathering some momentum in the 1990s and the early 2000, its popularity was restricted to a handful of UN agencies (e.g. UNICEF, UNDP), bilateral aid agencies (e.g. Norwegian Norad, British DFID) and international organisations (e.g. ActionAid, CARE). The claim that poverty persists partly because the poor do not enjoy legal rights (and that over three billion people currently live without legal protection), popularised the legal empowerment approach that evolved parallel to the HRBA discourse. And 7 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) considerable momentum was generated with the establishment of the Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor (CLEP) in 2005. The informal sector suddenly returned to being the focus of research and policy attention again, including the range of problems faced by the poor who are often confined to, and operate within, the informal economy. Thus the LEP approach began highlighting the local complexities and nuances of land reforms and peasants rights; how “formalisation” (including enforcement of property rights in the informal economy, providing legal identities and titles of ownership) can benefit the poorest of the poor and marginalised groups, particularly women; the role and status of certain unique and flexible traditions of collective rights among indigenous groups; and the capacity of the formal judicial system to live alongside customary law, promote socio-economic equity and prevent elite capture. The international discourse on the relationship between law and development was, for many decades, largely centred on improvements of the content of laws, the working conditions and facilities available to lawyers and strengthening the capacity of state institutions. The World Bank and other organisations continue to believe that rule of law is directly related to per capita GDP, and that citizens will benefit from economic growth when their governments uphold the rule of law. Numerous critics of this emphasis on the rule of law (Golub 2003; Carothers 2003) highlight the uncertainty of economic and political benefits (e.g. democracy) that result from improvements in the rule of law. The LEP approach, in contrast, has emphasised the provision of, and access to, legal and institutional tools by the poor. An influential report by the 8 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor (hereafter CLEP report) defined LEP as ‘the process of systemic change through which the poor and excluded become able to use the law, the legal system and legal services, to protect and advance their rights and interests as citizens and economic actors’ (CLEP 2008, 3). Rather than simply providing advice, lawyers were encouraged to view the poor as partners, so as to encourage people to participate directly in influencing public policy and priorities. Legal empowerment also places emphasis on the use of nonjudicial strategies, which may in certain situations be better able to address the concerns of the poor. Laws in many poor countries typically work against the poor, and hence the LEP approach advocates a better integration of law into a broader package of development-related activities (Golub 2003, 3-4) by placing emphasis on the ‘use of legal services and related development activities to increase disadvantaged populations’ control over their lives’ (Ibid.). The CLEP Report, which proposed a framework of legal empowerment based on four pillars – access to justice and rule of law, property rights, labour rights and business rights, argued that the main goal of a LEP approach is to protect poor people from injustice (e.g. wrongful eviction, expropriation, extortion, and exploitation) and offer them ‘equal opportunity to access local, national, and international markets’ (CLEP 2008, 28). Not surprisingly, the pillar pertaining to access to justice and the rule of law was considered to be the most important, providing an enabling framework for the remaining three pillars. Accordingly, the LEP approach claims that large parts of the developing world must implement reforms aimed at ensuring the right to legal identity (e.g., registration at birth), 9 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) repealing or modifying discriminatory laws, strengthening the work of civil society organizations, supporting alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, supporting paralegals, improving the workings of the police force, creating accessible judicial and land administration systems that recognize and integrate customary and informal legal procedures and focusing on the legal empowerment of specific groups such as women, refugees, indigenous populations and internally displaced persons (CLEP 2008, 5-6; 31-34). There are many benefits of pursuing HRBA and LEP in the fight against poverty. These approaches highlight the distinct character and normative force of law, the equal manner in which legal standards are applicable to all actors, the potential use of codified international legal standards to criticise government action or inaction and the ability to recognise the state as the primary duty bearer in promoting human development. The HRBA and LEP approaches have been the subject of substantial praise as well as strong criticism. I have discussed these in detail elsewhere (Banik 2009; 2010). In the context of this essay, two broad sets of criticisms appear particularly relevant. The first set of issues relate to the allegation by several scholars and development practitioners (especially at country levels) that these approaches are mainly rhetorical (rights and empowerment are proclaimed) rather than forwarding concrete advice for the practical implementation of development policies (Eide 2006; Banik 2010). Related to this is the claim that the approaches lack conceptual rigour and virtually all current efforts can be loosely labelled as “rights-based” or aimed at promoting empowerment of people living in poverty. 10 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) As Darrow and Tomas (2005, 537) observe, ‘continued credibility of rights-based approaches demands a higher degree of conceptual rigor and clarity than has prevailed in the past, along with a frank appraisal of their relative strengths and limitations’. Many development practitioners, including the staff of NGOs and UN agencies believe that the human rights community is preoccupied with events taking place in UN headquarters and donor country capitals, where good intentions and appealing buzzwords are reiterated without there being appreciation for ground level realities. Developing country governments often pay lip service to human rights language, include binding obligations, and are reluctant or unwilling to push for adoption and closer integration of internationally ratified human rights instruments into national law and policy making. Others point to the obsession of the international community to propose new buzzwords, rather than concentrating one how established approaches can be improved. Hence Sengupta (2008) argues that the LEP approach builds on human rights principles and will have most impact if it is viewed as a sub-set of the HRBA, rather than an independent set of strategies for developing countries to pursue. The second broad set of criticisms relate to the challenge of translating global theory into national and local practice. These mainly relate to the lack of conceptual clarity of both approaches at programmatic levels – where anti-poverty policies are implemented. There are concerns that HRBA and LEP do not provide adequate tools for the actual design and implementation of required programmes and projects. In spite their theoretical underpinnings, the HRBA and LEP have 11 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) proved difficult to operationalise in practice, particularly in relation to socioeconomic rights such as those related to food, water and health. This is because, as Alston (2005, 802) argues, HRBA criteria are much too often ‘expressed at a level of abstraction and generality that is not uncharacteristic of some human rights discourse but that is likely to seem abstract, untargeted, and untested to the community of development economists’. Consequently, policymakers and those implementing public policy do not believe that the HRBA provides concrete advice and guidance on how to address complex challenges and trade-offs on the ground. A crucial step to understanding and thereby evaluating the impact that the HRBA and the LEP can have in relation to specific socio-economic rights to understand the factors that explain the considerable gap between the international human rights discourse and instruments on the one hand and the politics of incorporating the same discourse in national settings. And both HRBA and LEP tend to underestimate the ability of political actors to ignore, bypass or selectively implement judicial recommendations and verdicts. Despite the obvious merits of the above criticisms, and I have often been critical of both approaches in my previous work, there is emerging evidence to suggest that HRBA and LEP can indeed be usefully applied in the fight against poverty. Using the case of the social and judicial activism on the right to food in India, I aim to illustrate some concrete successes that have been achieved using a combination of the strategies advocated by HRBA and LEP. 12 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) PART 2: SOCIAL AND JUDICIAL ACTIVISM ON THE RIGHT TO FOOD IN INDIA While there is a widespread belief that the home of the malnourished child is subSaharan Africa, all available data clearly show that the worst affected region is South Asia. The enormity of the problem is borne out by the fact that India accounts for one third of the world’s undernourished children, every third woman in the country is undernourished, and 55.3 per cent of Indian women are anaemic. Moreover, an intergenerational cycle of undernutrition is perpetuated when 22 per cent of children are born underweight and thus susceptible to numerous infections. Although there has been some progress in reducing undernourishment, from 240 million in 1990 to 217 million in 2012 (FAO 2012), India ranked 65th among 79 countries in a recent Global Hunger Index; with an estimated 19 per cent of the population that is undernourished (IFPRI 2012), the country is far from targets meeting its Millennium Development Goal targets scheduled for 2015. Indeed, improvements in nutritional status have not kept pace with the country’s impressive economic growth in the past decade. This stark reality prompted the Indian Prime Minister to admit in January 2012 that the “the problem of malnutrition is a matter of national shame” and that the country has not managed to reduce hunger “fast enough”.2 2 ‘Full text of PM's speech at the release of the HUNGaMA Report’, NDTV, 10 January 2012, http://www.ndtv.com/article/india/full-text-of-pm-s-speech-at-the-release-of-the-hungama-report165450 (Accessed: 01 September 2012). 13 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) The daily presence of food insecurity (difficulties in accessing and consuming adequate amount of good quality food) facing large groups in the Indian population – and the more sensational media reports of ‘starvation deaths’ in various parts of the country amidst large amounts of food rotting in storage houses – has been an issue that has attracted the attention and interest of the media, civil society organisations, political parties and, in particular, the Indian judiciary. A main catalyst for litigating economic, social and cultural rights in India was the series of radical changes undertaken by the Supreme Court since the 1980s, which popularised so-called public interest litigation (PIL). These initiatives not only pre-date the legal empowerment approach, but also allow lawyers, civil society organisations, or any other organisation to petition the court in order to protect and promote universal human rights. And not only have the requirements of standing been widened to allow anyone to litigate in the public interest, but fact finding initiatives by the court have been institutionalised, and the judiciary has assumed supervisory powers to monitor the implementation of its own orders. The courts in India have thus experienced a radical transformation of their roles in safeguarding human rights, especially the right to life (Fredman 2008: 124). The result has been hundreds of cases concerning the enforcement of economic, social and cultural rights through the use of PIL. In addition to food, the right to health, medical care, education, housing and clean and healthy environment, have also been addressed by the courts through PIL cases (Banerjee et al. 2005; Gonsalves 2008). Despite the ever increasing number of PILs handled by courts in India, one particular case – related to the right to food – has not only received much national 14 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) and international attention, but has also achieved concrete policy outcomes. This is the focus of the ensuing sections of this essay and illustrates the operationalisation of the HRBA and LEP in practice. Judicial activism on hunger and starvation deaths: 1980s—1990s The Indian courts have a long history of intervening on matters related to food security and drought relief. In the mid-1980s, the media began reporting on the drastic rise of starvation deaths and related suffering such as forced migration, and child sales. The eastern state of Orissa was particularly singled out in such reports, with one particular district in Orissa – Kalahandi (literally meaning ‘black pot’) receiving the most media and political attention. Two social workers from Kalahandi district filed a PIL in the Supreme Court in October 1985 and drew attention to large groups of people facing destitution and starvation as a result of recurrent droughts and resulting food shortages.3 The petition claimed that antipoverty programmes implemented by the Orissa government had failed to deliver benefits, and that large groups of people in the district were facing starvation and destitution. A similar PIL was filed in the Supreme Court in 1987 by the Indian People’s Front (a breakaway faction of the Communist Party of India), which alleged that destitution and starvation deaths had become a regular feature of Kalahandi and neighbouring districts due to the callous attitude and negligence of the Orissa government.4 It requested the Court to investigate the Orissa 3 PIL Writ Petition (Civil) No. 12847 of 1985, Kishan Pattnayak and Another vs. the state of Orissa, Paragraph 1 (quoted in Currie 1998: 423). 4 Writ Petition (Civil) No. 1081 of 1987, the Indian People’s Front through its Chairman, Nagbhushan Patnaik vs. State of Orissa. 15 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) government’s inaction in these districts highly vulnerable to starvation. Upon receipt of the two petitions, the Supreme Court appointed a district judge to conduct an inquiry. The ensuing report, submitted to the Court in 1988, did not establish any cause to criticise the Orissa government’s efforts and the judge concluded that no starvation deaths had taken place. This conclusion, however, was highly criticised by the petitioners and the media, and even the Supreme Court distanced itself from the report, concluding in 1989 that there was considerable evidence the starvation deaths had indeed occurred in Kalahandi, and the Orissa government was instructed to be more active and responsive to the needs of households vulnerable to extreme poverty and hunger.5 Through the late 1980s, similar PILs were filed in the Orissa High Court, highlighting cases of bonded labour, forced migration of large groups of people fleeing from starvation, child sales, and exploitation of indigenous groups by village elites.6 In early 1992, the High Court passed its final ruling on these cases and concluded that its own investigation had established several cases of starvation deaths and hence the Orissa government was directed to pay compensation to the families of the deceased. The Court was highly critical of the implementation of social welfare programmes, and held two senior civil servants accountable for failing to take quick and appropriate action to prevent human suffering in Kalahandi and adjoining areas. The immediate impact of the judicial interventions was a drastic increase in media attention on Kalahandi and pressure on the Orissa government to react. 5 Order, Supreme Court of India 1989, Paragraph 7. Case No. 3517/88 filed on 17 October 1988, Bhawani Mund vs. State of Orissa; Case No. 525/89 filed in 1989, A. C. Pradhan vs. State of Orissa. 6 16 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) Indeed, the Orissa High Court’s ruling was the first time in history that a public authority in Orissa had concluded that starvation deaths in Kalahandi had actually occurred. Successive ruling parties since 1985 had denied all such claims. The adverse publicity on the state of governance in Orissa that followed the Court rulings that began in the late 1980s appeared to also have an impact in the elections, with the ruling (Congress) party being voted out of office in 1990. However, when the Orissa High Court confirmed starvation deaths in Kalahandi in 1992, the new government formed by the Janata Dal party began blaming the previous government for its failures instead of initiating radical change to address vulnerability to hunger in starvation-prone areas. And despite the fact that reports of starvation deaths in Kalahandi and other districts in Orissa continued to appear in local and national dailies right throughout the period this government was in office, the major political actors in charge of the state largely ignored judicial recommendations to radically reformulate guidelines for improving administrative response to starvation (Banik 2007). Although a handful of civil society organisations and concerned citizens kept the starvation deaths issue alive in the media, in addition to petitioning the courts and quasi-judicial organisations such as the National Human Rights Commission, the Orissa government showed little interest in making drastic changes to its social welfare and drought relief policies. Thus, although there was considerable media interest in the stories of starvation deaths taking place in Kalahandi, and the highest levels of the judiciary was mobilised by civil society organisations and other well-meaning local actors, the direct impact of these actions on people vulnerable to starvation was negligible. 17 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) Social movements and litigation on the human right to food in India The 1990s witnessed a growing interest on extreme poverty and food-related deprivation in the media and political discourse. When major national newspapers began to publish news articles on starvation deaths in many parts of the country despite an abundance of food available in government storage houses, the People’s Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL) – a coalition of fifty-six civil society organisations – became actively involved in seeking judicial redress on behalf of households facing destitution and starvation. Using the language of the HRBA, the Rajasthan branch of PUCL submitted a PIL to the Supreme Court in April 2001 questioning whether the right to life guaranteed under article 21 of the Indian Constitution also included the right to food.7 The petition requested the Court to intervene to prevent starvation deaths that were taking place despite surplus food stocks in possession with the central and state governments. It further asked, ‘Does not the right to food which has been upheld by the apex Court imply that the state has a duty to provide food especially in situations of drought to people who are drought-affected and … not in a position to purchase food?’8 Using the human rights language of duty-bearers who must act to respect, protect and fulfil the rights of the poor, PUCL identified central and state governments in India as the main duty bearers with the obligation to protect the right to food. It further argued that these duty bearers must be held to account for their failure to assist individuals and households facing acute hunger and 7 Writ Petition (civil) 196 of 2001, submitted in April 2001. ‘PUCL petitions Supreme Court on starvation deaths,’ PUCL Bulletin, July 2001, http://www.pucl.org/reports/Rajasthan/2001/starvation_death.htm (Accessed: 10 September 2010). 8 18 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) starvation while large stocks of food remained hoarded in government storage houses. The petition also requested the Court to push the government to address the implementation shortcomings of the country’s main social security programmes such as Public Distribution System (that provides subsidised food and other items to poor households), and ensure that vulnerable groups in the population (e.g. impoverished women, children and the aged) were adequately covered and targeted by public policy. The Supreme Court is yet to award a final verdict in the case, but since 2001, it has held hearings at regular intervals and issued over one hundred very detailed ‘interim orders’ that are considered applicable as law until the case is closed. While the PIL was initially brought against the government of Rajasthan, thanks to civil society activism and mobilisation, it now applies to all state governments in India. Further, the case does not only address the problem of hunger, but also issues of food insecurity, urban destitution, right to work, transparency and accountability in government and the implementation of social security programmes. The case is currently coordinated, on behalf of the petitioners, by the Human Rights Law Network – an organisation of lawyers and social activists working to use the legal system to advance human rights.9 Despite hundreds of PILs filed every year, this particular case has been the Indian judiciary’s most prominent attempt to make economic, social and cultural rights justiciable. In the process the case has received widespread attention both at home and abroad. In 9 The case is technically known as PUCL vs. Union of India and others (Writ Petition [Civil] No. 196 of 2001). 19 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) the following sections I will discuss four main categories of impact that this ongoing case in the Supreme Court has had, followed by a separate section on the recently enacted National Food Security Bill.10 First, some of the most important anti-poverty programmes in the country were converted into legal entitlements, i.e. the government could not stop or make major changes to these without the approval of the Supreme Court. For example, the Court delivered a landmark judgement in November 2001 on eight specific programmes or schemes with a food component. Among its recommendations, the Court ordered full implementation of the Public Distribution System that offers subsidised food to below poverty line households, converted a previously voluntary programme (Mid-Day Meal Scheme) to provide cooked meals at schools to an obligation on the part of all states, and ordered improved implementation of the Integrated Child Development Services, which provides assistance to pregnant and nursing women and children, and other programmes aimed at helping impoverished families whose primary breadwinner has died. With this particular order, the Court converted the benefits of the eight programmes into legal entitlements and hence provided all programme beneficiaries with the ability to claim benefits as a matter of right, and seek judicial redress if such rights were violated (Right to Food Campaign 2005, 10). This particular order together with previous and subsequent interim orders has thus given rise to a set of ‘umbrella orders’ (applicable to all relevant social programmes) and more specific orders relating to the functioning of specific 10 This section has benefited from personal communication with Kavita Srivastava, the National General Secretary of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), during her visit to Stanford University in November 2013. 20 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) social protection programmes. These umbrella orders cover numerous issues including the identification of agent(s) or agency with responsibility for compliance (mainly Chief Secretaries in the various States) and village councils (or Gram Sabhas) that can demand accountability by accessing all relevant information; monitoring the functioning of government programmes and investigating misuse of funds.11 Second, various levels of government in India have quite regularly been held to account by the Supreme Court. For example the highest civil servant in each state (the Chief Secretary) is now required to be present during certain hearings in order to put forward the government’s views on food security. And the Court has established a new mechanism for ensuring compliance with, and the monitoring of, its orders by appointing two commissioners in 2002 to monitor and report on the implementation of a whole range of public welfare programmes. The commissioners were given the power to investigate potential violations of the interim orders and to demand redress from the political and administrative leadership, with the full backing of the Supreme Court.12 In addition to providing periodic reports to the Court, the commissioners are authorised to seek responses from State governments, investigate complaints from civil society organisations and set up relevant enquiry committees (Right to Food Campaign 2005, 7-8). A major impact of these initiatives has been the gradual increase in the amount of funds allocated by State governments for improving coverage of social security programmes within their territories (Right to Food Campaign 2012). 11 12 Interim order, Supreme Court, 08 May 2002. Interim order, Supreme Court, 29 October 2002. 21 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) Third, essential services provided by the government are now becoming legal rights as a result of this on-going case. The impact is not only confined to the right to food, but there have been important spill over effects in relation to other social and economic rights including the right to education and the right to work. Thus, the orders issued by the Supreme Court on the right to food case so far have catalysed the Indian government to enact some very progressive legislation on other socio-economic rights. Fourth, the actions of the Supreme Court and the ensuing interim orders have encouraged regional (state) governments in India to enact legislation of their own in order to improve service delivery. One prominent example is Chhattisgarh, a state which ranks low among other Indian states in relation to human development, where the government successfully enacted the Chhattisgarh Food Security Act in December 2012 with the aim of ensuring ‘access to adequate quantity of food and other requirements of good nutrition to the people of the State, at affordable prices, at all times to live a life of dignity’. With several innovative features related to targeting of vulnerable food insecure households, availability and distribution of various types of food, and speedier mechanisms for service delivery, this piece of legislation has been hailed as a major success story amidst the general reluctance of state and national governments in India to abide by the directions of the central government and the Courts that are aimed at improving food security. One of the most important impacts of the right to food movements has been the recent enactment of national legislation on food security, which was a 22 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) direct result of the growth and popularity of a human rights-based approach to development in the national political discourse. Human Rights-based policy intervention: The National Food Security Bill As a direct result of the ongoing right to food case in the Supreme Court, and following decades of civil society and judicial interest on food security, the Indian parliament finally passed the National Food Security Bill (hereafter NFSB) in August 2013. This was the culmination of a series of promises by the central government in New Delhi, led by the United Progressive Alliance, since being voted back to power in 2009 and concerted efforts by civil society organisations to legislate a bill specifically focused on food security. The NFSB was also the product of several years of deliberation, often at the prodding of the National Advisory Council headed by the President of the Congress Party, Sonia Gandhi, and consisting of several well-known academics and civil society activists working on food and nutrition-related issues. Despite the delays in enacting the legislation, and the innumerable compromises in the final draft, the NFSB has been hailed by many societal and political actors as a watershed. Some of the features of the Bill include the ambitious goal of providing up to 75% of the rural population and up to 50% of the urban population of monthly foodgrains per person or per household. There is a focus on exclusive breastfeeding of children below six months while for children between 6 months and 6 years, the Bill provides for a free ageappropriate hot-cooked meal. And for children aged 6-14 years, one free mid-day 23 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) meal every day (except on school holidays) will be provided in all government and government-aided schools up to eight grade. Similarly, pregnant women and nursing mothers are entitled to a free meal every day during pregnancy and six months after childbirth, and there are provisions for basic maternity benefits. Another progressive feature aimed at promoting empowerment of women entails that women of eighteen years of age or above will be considered to be the household head when ‘ration cards’ (that serve as proof of identity and status as programme beneficiary) for subsidised food programmes are issued. A relatively new feature to the Indian system of social protection – inspired by the conditional cash transfer models successfully implemented in Brazil and Mexico – is the right to receive food security allowance (or cash transfers) in situations when ‘the entitled quantities of foodgrains or meals to entitled persons’ are not available (NFSB 2013, Sec. 13.). The main responsibility for the implementation of the NFSB provisions belongs, however, to state governments, ‘in accordance with the guidelines, including cost sharing, between the Central Government and the State Governments in such manner as may be prescribed by the Central Government’ (Ibid., Sec. 7). In addition, state governments are expected to constitute a 7member State Food Commission for monitoring and reviewing the implementation process, with at least two women members and one member each from traditionally disadvantaged communities (Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities). The NFSB also provides for the redress of complaints and grievances, including call centres and help lines. 24 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) From a HRBA perspective, the most important step forward is the recognition in the Bill of explicit duties or ‘obligations’ of various levels of government for the promotion of food security. Thus, the main obligation of the central government is to provide foodgrains (or adequate funds) to state governments at specified prices. State governments, however, have the main duty to implement the provisions of the Bill together with local government institutions, and may extend the level of benefits with additional resources from their own coffers. Despite the obvious benefits of legislating the right to food and guaranteeing access to food to large sections of the population, the NSFB has been heavily criticised by opposition political parties and other societal actors, including PUCL. These include the following: lack of focus on nutritional rights; ambiguity in terms of identifying food insecure households; the enormous costs associated with covering the very large group of proposed eligible beneficiaries; the persistence with flawed social protection programmes (such as the Public Distribution System) without undertaking major reforms; the reluctance of state governments to bear additional costs and be accountable to the central government for implementation failures; and fears that the central government will discriminate against states controlled by opposition parties. Despite these very valid concerns, the NFSB appears to be a step in the right direction, and if properly implemented, can make a major impact in improving economic, social and cultural rights for hundreds of millions of people in India. 25 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) CONCLUDING REMARKS The Indian case provides a useful prism to test the added value of applying a human rights and legal empowerment lens to addressing the pressing concern of chronic and acute hunger that affects large sections of the global population. Although the rulings of the Indian Supreme Court and lower level courts in the 1980s and 1990s helped to focus considerable media attention on certain starvation-hit areas of India and put several state governments on the defensive, there was very little political and administrative commitment to follow up the judicial recommendations. It is now widely recognised that simply a focus on law and judicial institutions is inadequate for fostering and promoting economic development and well-being. In addition to legal empowerment, there is also need for genuine political empowerment where citizens are not only aware of their rights, but also in a position to successful claim them. The added value to pursuing a HRBA in relation to human development are numerous, and include a focus away from viewing development as charity and a specific outcome or achievement to one where development interventions are evaluated on the process by which they empower the poor. The right to food movements in India (but also elsewhere such as Brazil and South Africa) have indeed documented some impressive results, particularly in terms of concrete policy outcomes. And although numerous challenges remain, the Indian experience provides some useful insight into the conditions under which a focus on rights and empowerment can actually be successful in fighting poverty. 26 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) An important criterion for success is when people living in poverty are better identified and targeted by public policy. Undertaking this task in a country as large and diverse as India is not an easy task, as previous experiences with social protection programmes have shown. Nonetheless, the on-going right to food case shows that civil society and the judiciary have provided valuable suggestions and recommendations to administrators and political leaders regarding the use of alternative methods for identification and targeting of beneficiaries. Many of these suggestions now form an integral part of the NFSB, which include recognising the status of women as household heads and the use of identity cards (increasingly with biometric information) for providing food rations or cash transfers and checking the abuse of resources. The challenges that continue to exist include extending coverage to remote areas of the country and limiting political clientelism where politicians take undue credit for distributing resources. Moreover, greater awareness is required among all groups in society on what it means to be a right holder and a duty-bearer, and how one can effectively claim one’s rights and carry out one’s duties. Another criterion of successful rights and empowerment-based approaches is when public policies focus on daily vulnerabilities, rather than being emergency-oriented responses. The traditional Indian response to past food shortages and allegations of starvation deaths has usually been crisis-induced. The political leadership is quite successful in mobilising efficient administrative response to clearly visible and substantially large crises such as resulting from floods and cyclones. In contrast, the less visible impacts of recurrent droughts and 27 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) hidden hunger do generate the same type of urgent political-administrative response. This is where the NFSB, if implemented well, can make a major difference by addressing the problems of chronic hunger by guaranteeing individuals and households access to basic amounts of food and essential commodities either for free or at affordable prices. Another key ingredient to the NFSB’s success will be how well its provisions and goals are understood and implemented by civil servants. The successful application of a HRBA requires that the attitudes and practices of civil servants change from arrogance to one of genuine commitment and service to those they serve. This is easier said than done, and some of the major social protection programmes implemented in India would work even better if corruption and leakages were kept in check and officials were more motivated in their jobs and better understood their functions as duty-bearers. What, then, does it mean to be a duty bearer? The evidence from India shows that politicians and bureaucrats resort to a considerable amount of blame-game whenever they are criticised for programme failures. Moreover, most power holders in India or other developing countries do not understand the concept of a duty bearer in the human rights sense. The general attitude remains one of providing charity to the masses in the form of hand-outs, which are distributed for gaining popularity and votes before elections. The problems of undernutrition and starvation in many Indian states (e.g. in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh) are highly prevalent among indigenous groups (often referred to as ‘tribals’), who are often the targets of social, economic and political discrimination, exclusion and marginalisation. 28 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) A frequent criticism of development programmes is that they often are heavy top-down in character, decided by power holders far removed from groundlevel realities and without consultations with intended beneficiaries. While the right to food movement in India did not involve a mass mobilisation of the poor, it is nonetheless a good example of civil society organisations pooling their resources and organisational skills to garner support and attention on the failure of public policy. Here, the role of lawyers working for the rights and empowerment of the poor has been crucial, as exemplified by the active contribution of members of the Human Rights Law Network, who have represented the petitioners of the right to food case in the Supreme Court, and have been credited for pioneering work in the field of public interest litigation in India. In the past few years, India has witnessed a growth in social movements that have initially focused on specific topics (e.g. corruption) and later metamorphosed into political entities. The Aam Admi Party (AAP) that started off as an anti-corruption movement, and which has recently formed the government in Delhi, is a good example of a movement that has exerted considerable political influence with the backing of India’s middle class. It remains to be seen whether and to what extent the AAP can exert political influence and continue to champion the rights of the poor. The sad reality is that in many parts of the developing world, including India, opposition political parties have simply performed an adversarial function in order to gain power, and then largely ignored these very same causes when they have assumed positions of authority. The HRBA and LEP approaches require that in addition to media and civil society 29 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) organisations, political parties must revamp their organisational and incentive structures and work towards promoting increased answerability and accountability of state institutions. In other words, governments must be forced to prioritise development efforts in, and resource allocation to, regions irrespective of personal and political ties. Similarly, the functioning and influence of oversight agencies such as the Ombudsman and Human Rights Commission are crucial. The provisions in the NFSB for food commissions with the power to address complaints and abuse of resources at local levels will only have a major impact if these institutions and their office bearers are given adequate resources and able to work independent of political interference. While the judiciary can hold authorities to account for failing to protect the rights of the poor, the verdicts of the courts must have teeth. Public interest legal representation on the right to food in India, Brazil and South Africa show that the use of the legal system has not only advanced the right to food in these countries but also strengthened other economic, social and cultural rights. However, for judicial interventions to have a major impact, the actions and recommendations of the courts must be taken seriously by the political and administrative leadership. There are often no strict sanctions for non-compliance, and many governments around the world routinely ignore or sidestep court orders. Rhetorical statements and appealing buzzwords are increasingly commonplace in development and policy circles. The urgency of world poverty requires not just talk, but genuine political commitment and concrete action. 30 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) REFERENCES Alston, P. (2005) ‘Ships Passing in the Night: The Current State of the Human Rights and Development Debate Seen Through the Lens of the Millennium Development Goals’, Human Rights Quarterly 27: 755-829. Banerjee, U. D., Naidoo, V., and Gonsalves, C. (2005) ‘The Right to Food Campaign in India: A Case Study of Entitlement-Oriented Rights-Based Strategies Used to Reclaim the Right to Food for Vulnerable and Marginalized Groups’, in U. D. Banerjee (ed.), Lessons Learned From Rights-Based Approaches in the Asia-Pacific Region, Bangkok: UNDP and OHCHR. Banik, D. (2007) Starvation and India’s Democracy, London: Routledge. Banik, D. (2009) ‘Legal Empowerment as a Conceptual and Operational Tool in Fighting Poverty’, Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 1(1): 117-131. Banik, D. (2010) Poverty and Elusive Development, Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. Birchfield, L. And Corsi, J. (2010) ‘Between Starvation and Globalization: Realizing the Right to Food in India’, Michigan Journal of International Law 31: 691-764. Carothers, T. (2003) ‘Promoting the Rule of Law Abroad: The Problem of Knowledge’, Rule of Law Series working paper, Washington DC: Democracy and Rule of Law project, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. CLEP (2008) Making the Law Work for Everyone, volume 1, New York: Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor, UNDP. Darrow, M. and Tomas, A. (2005) ‘Power, Capture, and Conflict: A Call for Human Rights Accountability in Development Cooperation’, Human Rights Quarterly 27: 471–538. Jonsson, U. (2003) ‘A Human Rights-Based Approach to Programming (HRBAP)’, Human Rights-Based Programming Unit, UNICEF. Eide, A. (2006) ‘Human Rights-Based Development in the Age of Economic Globalization: Background and Prospects’ in B. A. Andreassen and S. P. Marks (eds), Development as a Human Right: Legal, Political, and Economic Dimensions, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. FAO (2012) State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012, Rome: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. Fredman, S. (2008) Human Rights Transformed: Positive Rights and Positive Duties, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Golub, S. (2003) ‘Beyond Rule of Law Orthodoxy: The Legal Empowerment Alternative’, Working Paper No. 41, Rule of Law Series, Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Gonzalves, C. (2008) ‘The Indian Supreme Court, ESC Rights and the Right to Food’, paper presented at the Human Rights and Extreme Poverty 31 Published in Patrick Keyzer, Vesslin Popovski and Charles Sampford (eds.) Access to International Justice, London: Routledge (2014) Conference on ‘Eradicating Poverty: Development and Empowerment of the Poor’, Kolkata, 5-6 December 2008. IFPRI (2012) Global Hunger Index 2011: The Challenge of Hunger – Taming Price Spikes and Excessive Food Volatility, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. NFSB (2013) ‘The National Food Security Bill’, Government of India, Available at: http://www.thehindu.com/multimedia/archive/01404/National_Food_Secu_ 1404268a.pdf (Accessed: 25 January 2014). Nyamu-Musembi, C. and Cornwall, A. (2004) ‘What is the “rights-based approach” all about? Perspectives from international development agencies’, Working Paper 234, Institute for Development Studies, University of Sussex. OHCHR (2006) Frequently Asked Questions on a Human Rights-Based Approach to Development Cooperation, Geneva: United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Sengupta, A. (2005) ‘Human Rights and Extreme Poverty’, Report of the UN Independent Expert on the Question of Human Rights and Extreme Poverty, Economic and Social Council, E/CN.4/2005/49. Sengupta, A. (2008) ‘The Political Economy of Legal Empowerment of the Poor’, in D. Banik (ed.), Rights and Legal Empowerment in Eradicating Poverty, Farnham: Ashgate. Pogge, T. (2005) ‘World Poverty and Human Rights’, Ethics and International Affairs, 19(1): 1–7. Right to Food Campaign (2005) ‘Supreme Court Orders on the Right to Food: A Tool for Action’, Available at: http://www.righttofoodindia.org/data/scordersprimer.doc (Accessed: 04 October 2010). Right to Food Campaign (2012) ‘Right to Food Campaign’s Critique of the National Food Security Bill 2011’, March 2012, Available at: http://www.righttofoodindia.org/data/right_to_food_act_data/events/March_ 2012_general_note_final_18_february_2012.pdf (Accessed: 16 October 2012) UNDP (2000) Human Development Report 2000, UNDP, Oxford University Press. Uvin, P. (2004) Human Rights and Development, Blommfield, Conn.: Kumarian Press. 32