Document 11380815

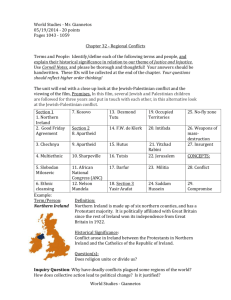

advertisement