Career Pathways Green Jobs and the Ohio Economy

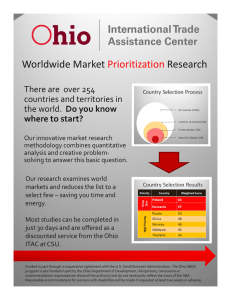

advertisement