I

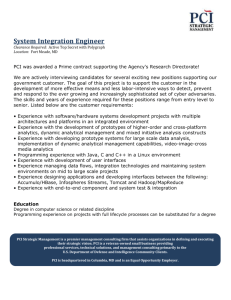

advertisement