MASSACHUSETTS LEAD POISONING PREVENTION ENVIRONMENTAL EQUITY

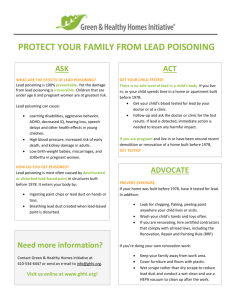

advertisement