GAO PIPELINE SECURITY TSA Has Taken Actions to Help

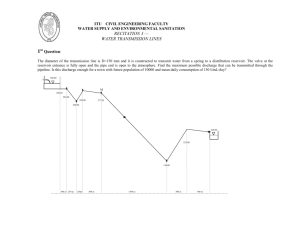

advertisement